If you see anyone inappropriately using the term roguelike to describe a game that does not even belong to the genre, send them this article.

I would like to clarify a misunderstanding that comes up often, this mistake around the word roguelike itself. The word is often used indiscriminately by people who have no idea what it actually refers to. Everyone makes the mistake so it’s pretty commonplace and it has become normal, thus a reminder of the definition of the word won’t hurt. With some luck, it will help people understand what they are talking about and hopefully stop spreading misinformation. My hopes are not too high, since TotalBiscuit already tried to do the same, and the word is still widely misused when it shouldn’t, but it’s worth a try. This article attempts to provide working definitions for the words roguelike and rogue-lite, as the two terms describe games that share two core design principles (permanent death and procedural generation), but they play very differently.

Reading, or watching a video? Pick your poison!

Roguelike as a separate genre

Roguelike is a genre in and of itself. It makes no sense to apply this word to platformers or first-person shooters for example, those are entirely different. Which means that if someone likes the classic roguelike genre and is asking for more games belonging to that genre, that person often receives irrelevant replies such as The Binding of Isaac. It’s as if someone was asking for a new FPS and you replied Hotline Miami because there are guns too.

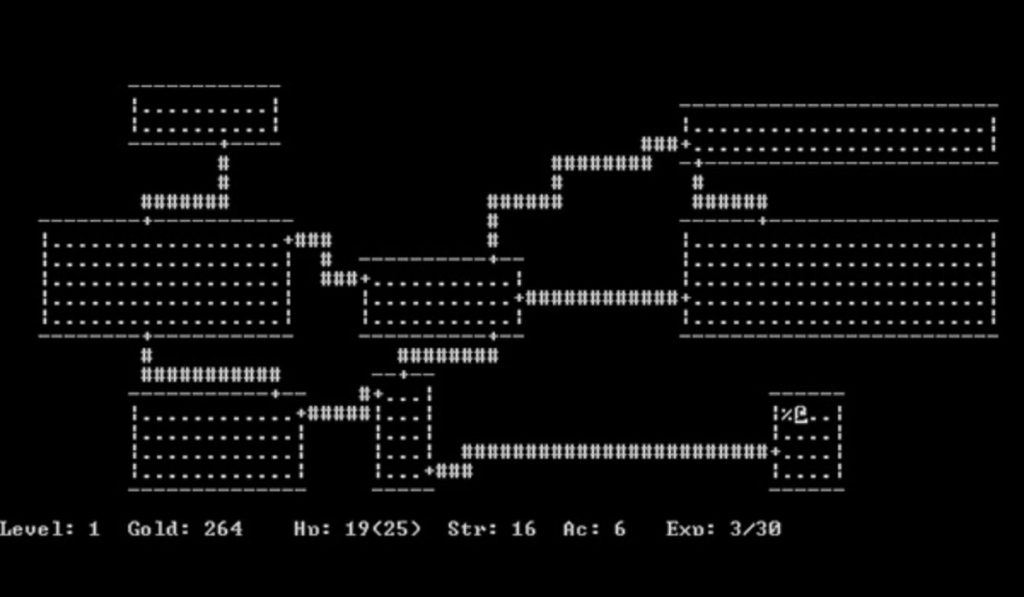

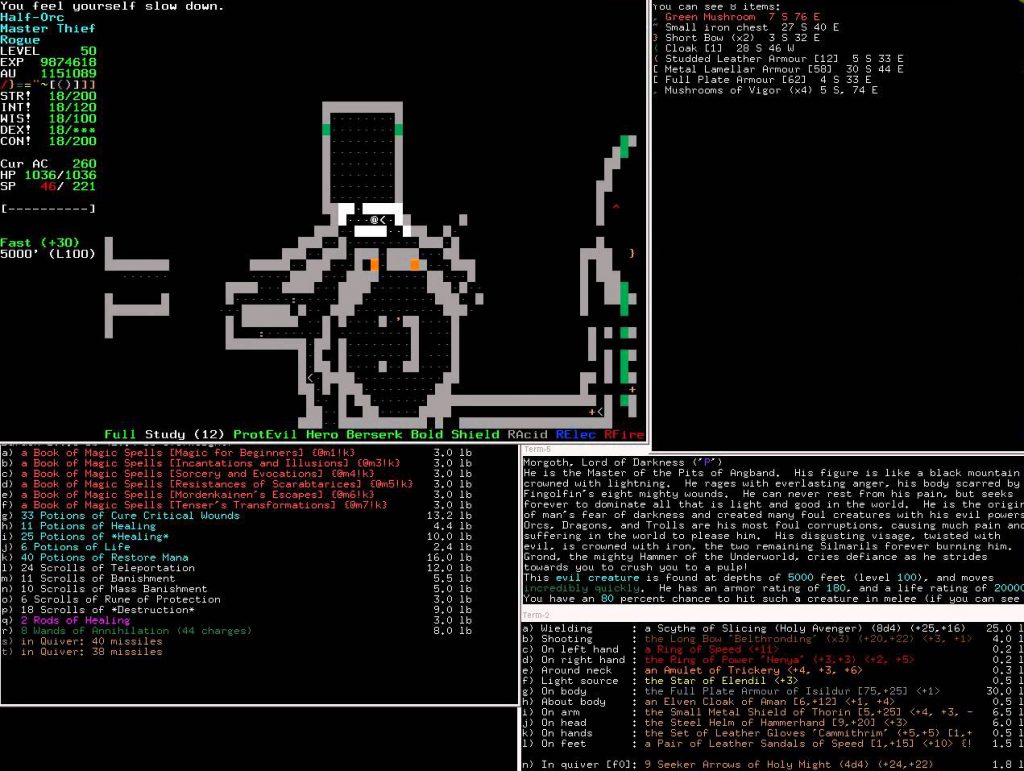

Initially, roguelike is a term used to describe games that are “like Rogue”. You can see what its top-down dungeons look like on the screenshot above, and don’t tell me that you see an FPS or a platformer. It’s a genre of games released in the 80s and 90s featuring games like Moria, NetHack, ADOM or Angband.

What makes a roguelike

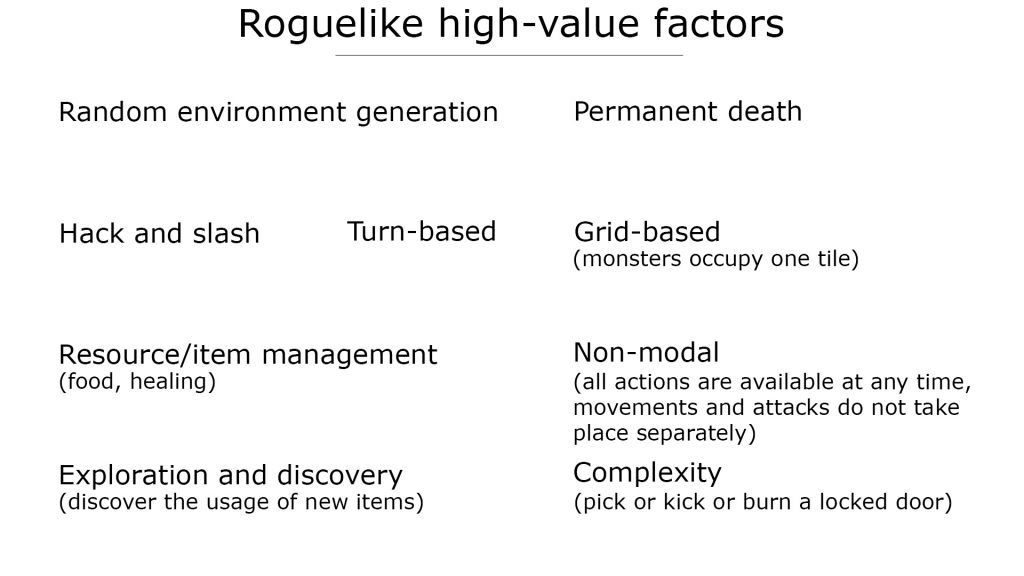

During the International Roguelike Development Conference 2008, specialists of the genre agreed on a specific list of characteristics that would help identify whether a game belongs to the roguelike genre. It was called the Berlin Interpretation and it is not a strict definition but rather a guide that lists all the ingredients that go into making a game “like Rogue“, as well as attributing a value to these characteristics. This list is a helpful tool in order to determine whether a game is classified as a roguelike or not: a pure roguelike will feature all these characteristics, but a game tuning down or missing some of these ingredients can still be classified as a roguelike if it doesn’t compromise too much on these characteristics. In order to determine how far a game can stray from the formula, each factor is attributed a value: high or low. High-value factors can be tampered with to some degree, but I would argue that their outright disappearance would disqualify the perpetrator from belonging to this specific genre. Low-value factors are often part of the expected experience, but their loss should not disqualify a game from belonging to the genre.

High-value factors are important in keeping the essence of what a roguelike is supposed to be. Most famously, they include permanent death and random environment generation, as you probably already knew. However, they also include the requirement that levels are made of a grid with each creature occupying one single tile, and the action has to be turn-based. So far it’s easy to remember, no? So next time someone pretends that a game is a roguelike and it’s not even top-down and turn-based, you can straight up slap them in the face and they should thank you; you will have done a good deed and prevented misinformation from spreading (more seriously: don’t do that, please). Another important factor is the importance of violence over diplomacy: hack and slash, and yet the game must have complexity to allow players to solve situations in various manners, such as kicking a door turn by turn until it breaks or quietly picking it. To provide the tools for this complexity, there is resource and item management with usually all kinds of potions that can be found by exploring the levels, and their function can only be learned through discovery which means some elements of trial and error when using an item. Traditionally, it is even possible to die from hunger! Lastly, the game should not be divided in several phases with different game mechanics: all actions should be available at any time; the game is non-modal.

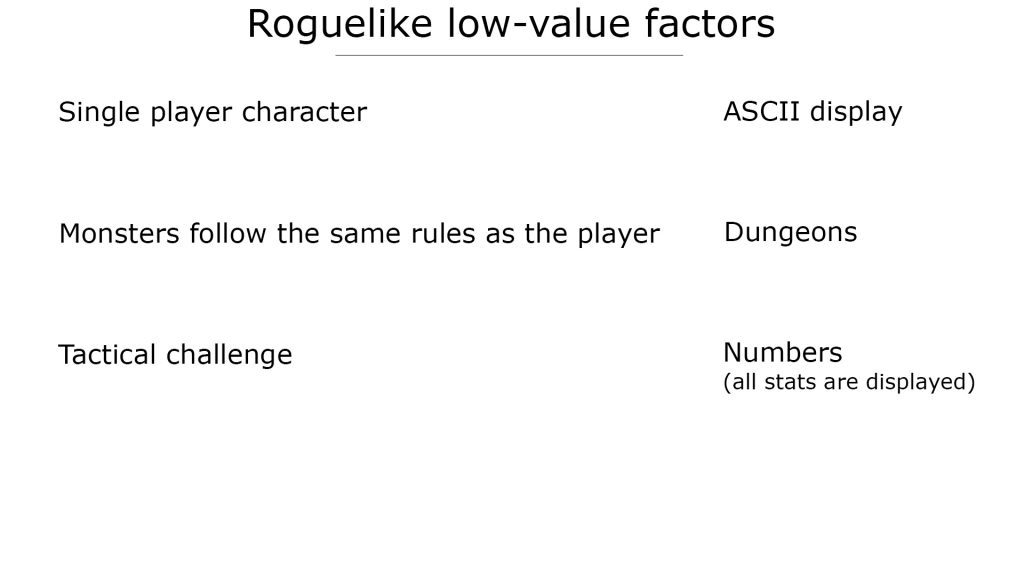

Low-value factors are part of Rogue‘s initial formula and are frequently seen in roguelike games. However, they are seen as non-essential and losing these characteristics alone would not be sufficient for a game not to be considered a roguelike, so I will not describe them all, you can refer to the Berlin Interpretation for more details. I will still mention that here we have the fact that monsters are supposed to follow the same rules as the players, so if you see a flying boss whereas your movements do not allow it, this characteristic has been lost. Please note that ASCII display is secondary: graphics are known to get better over time.

Next gen

Among modern roguelikes following these guidelines, while sometimes adding elements of a meta-progression, you can find Haque, Tangledeep, DragonFangZ or Paper Dungeons Crawler. So here you have it, roguelikes are their own genre separate from the rest, and most people never played a single true roguelike game considering how niche they are. Which is also why the general audience often confuses the terms roguelike and rogue-lite, since it does not know that roguelikes are a thing on their own.

Roguelike vs rogue-lite

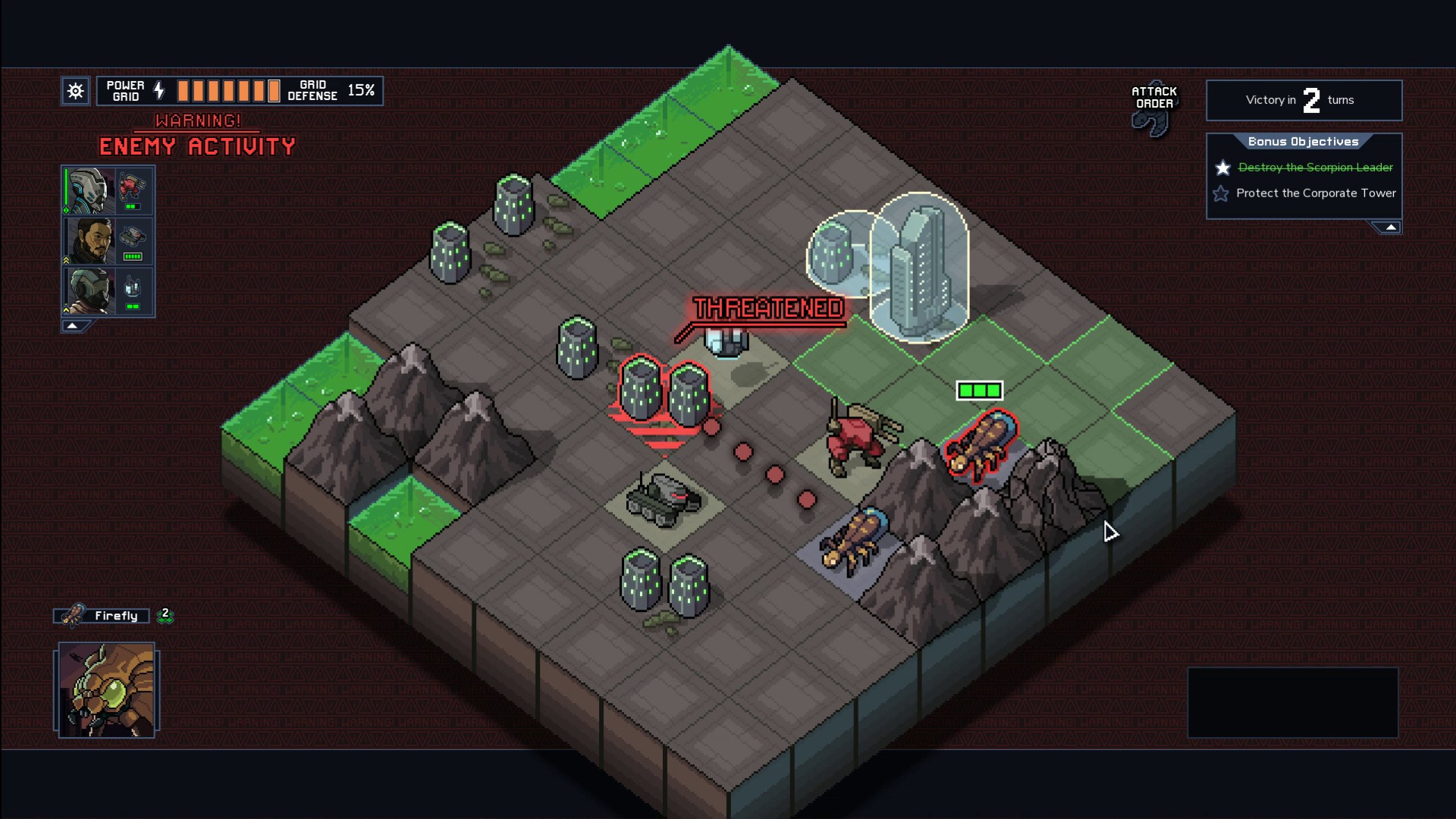

Just like all games featuring guns are not called first-person shooters, it’s still possible to take inspiration from their mechanics and apply them to another game, such as with Portal combining first person and puzzles. The same goes for roguelikes, some of their core game mechanics can be applied to another framework. In this case, we are not talking about a genre in and of itself, but common design principles transported to another genre. For example, these design principles can be added to a platformer or a tactics game. These core features have been grouped to form a system called rogue-lite, light as if there was a diet since it retains only a handful of features and not the rest. An alternative spelling commonly found is “rougelite”. Some used to say “roguelike-like”, which literally means “games that are like the games that are like Rogue”. On Wikipedia, “hybrid roguelike” also appears. At some point, some tried to push for the term “Procedural Death Labyrinths” to make the name sound different from roguelike, but it does not easily roll off the tongue and did not take root so its usage has been halted by now. The developers of the game Rogue Legacy are the first ones to have coined the term rogue-lite. Considering that most people never heard about Rogue and supposed that it probably was just another action platformer, confusion between roguelike and rogue-lite stemmed instantly. But at this point, it’s past due time to stop confusing everything and let traditional roguelike games live their life, while the derived games are labeled under rogue-lite to mark their difference. Hopefully, this article helps shed some light over the historical subtleties between these two categories, and can be used to find some clarity. Sadly, much of the confusion stems from using “Rogue” in the name of all these terms rather than coining proper new names.

What makes a rogue-lite

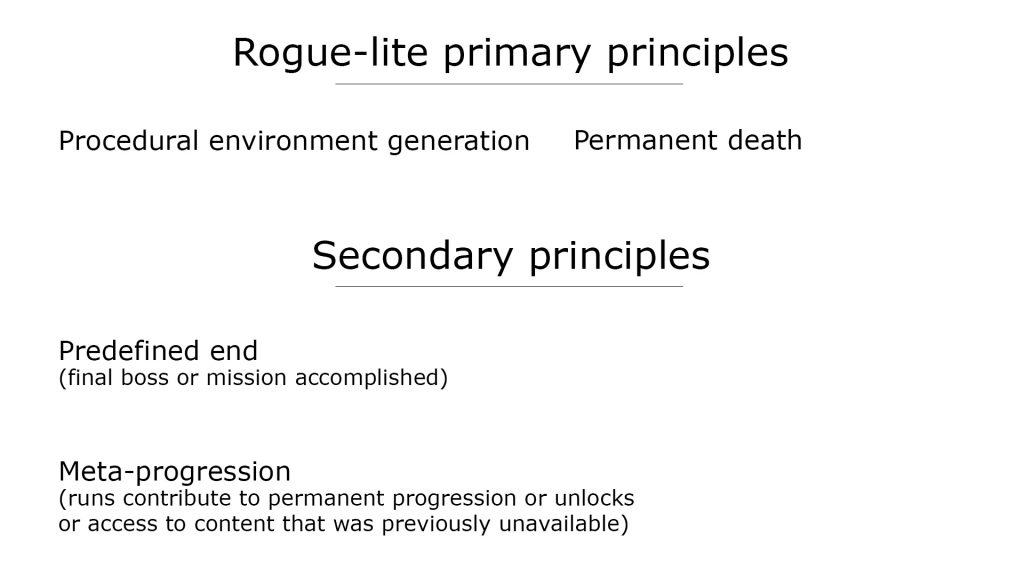

When talking about rogue-lite games, there are two obligatory principles for a game to belong to that category and then two frequent principles that are not obligatory.

The two primary principles are core design features inherited from roguelikes. Once again, there has to be some sort of permanent death that means the loss of a character and the equipment it was carrying upon death. This core principle is part of the expected experience contrary to games that simply propose to go back to a previous save by turning back the clock. Then, permanent death has to be combined with procedural environment generation, which means that the adventure will be different each run, by creating levels designed by an algorithm or made from the assembly of numerous hand-made pieces.

The two secondary principles give a global sense of progression to the player. They are not mandatory, but often allow for a structure that is more appealing to the general audience. There is a predefined end to the story or the adventure: a certain point when the game acknowledges that the player succeeded in their mission or met a final boss. Lastly, there is almost always a meta-progression or permanent progression, although it can take many different forms. Each run contributes to unlocking new items or upgrades to the character, to access new content that was previously unavailable or unlock shortcut portals.

Note: This permanent progression was absolutely not present in older roguelike games and they did not feature an ending either, but it is gradually coming to the recent games of that genre with, for example, unlockable characters or piggy banks to save coins across runs.

The two main design principles of rogue-lite games, permadeath and procedural environment generation, can be applied to a completely different genre that is not turn-based on a grid.

Rise of the rogue-lites

Besides the hardcore mode of Diablo, the first famous game to retrieve these elements and use them in a new genre was Spelunky by Derek Yu. This game impressed Edmund McMillen who then developed The Binding of Isaac. The Binding of Isaac then had a strong influence on the shaping of this style of games. It is also responsible for the trend that was to obfuscate useful information instead of displaying it, which pushed players to keep a browser tab open with the game’s wiki page, such as with Don’t Starve; thankfully, this trend is now on the decline.

The rogue-lite design seduced the indie games world and many games adopted its principles. For developers, it’s good because it allows creating a lot of content without having to do everything by hand, for gamers, it’s good because it permits launching the game often to face a strong challenge. Permadeath means that each tentative attempt has high stakes and a lot of tension.

Dark side of the rogue-lites

Since it became a trend, the rogue-lite brand was added to a lot of games in order to get people to talk about the product whereas without the rogue-lite aspect these games would be instantly forgotten since their core gameplay is not very fun. Furthermore, a lot of rogue-lite games rely too much on permanent progression to increase the player’s damage output in order to have enough chances to survive, which contributes to an artificial longevity of the title. Another issue is that always retreading the same steps can quickly become too repetitive. At first, there are lots of new things to see, but then you can get repeatedly stuck in the same environment with the same tools everytime. This is an interesting paradox, as randomness should provide wholly different adventures each time, and yet it can be limited or become streamlined to the point that each run feels all too similar. On the other hand, if everything relies on luck it’s possible to have garbage runs that you itch to restart because you were dealt a bad hand.

The total length of a run can have an impact as well. If a game can be finished in half an hour to one hour, restarting a new adventure is quick and easy. However, for adventures that last more than two hours it can be very off-putting to restart the game and realize you have wasted the rest of your evening.

One of the reasons that developers push for an increased longevity is that hardcore gamers love rogue-lites for their tough challenge and lack of saves. It harkens back to the 8-bit era when games had no saves allowed and it was obligatory to finish the adventure in one go. While there are gamers who indiscriminately want games that will keep them busy for 100 or 1000 hours, pushing the developers to design long and difficult games such as The Binding of Isaac, there are other developers who deliver shorter adventures such as City of Brass for gamers who enjoy a bite-sized experience of 10 to 20 hours.

Next gen

Over time, the rogue-lite spirit was refined and most of its initial brutality against players has been decreased. For example, Dead Cells has an overwhelmingly strong protagonist right from the start instead of beginning the adventure naked, weak and crying with good stuff only appearing after a few levels. A lot of games are starting to add teleporters to let players directly go back to the levels where they died rather than starting from the beginning over and over again.

Finally, to this day I find the elegant Into The Breach (from the creators of FTL: Faster Than Light) to be the rogue-lite game that has best refined and crystallized the formula. The reason why is that it’s possible to tackle its campaign in any order, and the characters/mechs, as well as secondary objectives and achievements, make each run something that is approached in a different manner to prevent repetition from setting in as quickly as in other rogue-lite games. Also, the whole content of the game can be completed within a reasonable span of time. It’s time well spent and not the developers making you waste it.

The rogue-lite systems have often been associated with platformers, but they have now been applied to many other genres such as CCGs with Slay The Spire or FPS games like Ziggurat… and the history of the latter games will be the subject of another article. So stay tuned, and enjoy the blooming rogue-lites as they are increasingly ambitious and refined, providing hours upon hours of brutal challenge!

My thanks to the late TotalBiscuit, fellow SoQ reviewer Spike and NoFrag reviewer Caroline, their words were of precious use to me before I started writing this article.

A very well written article RGK.

I agree with the selection of Next Gen suggestions, they are some of the better options and I would like to offer an additional Game title to the readers; Cave Blazers. It is one of the only Rogue-lite games i enjoy playing besides Dead Cells and I think it deserves mentioning.

https://store.steampowered.com/app/452060/Caveblazers/

Excellent article that provides accurate information. Thank you for your work!

Thanks for the article.

I found it very interesting and informative. I must say I do get confused sometimes so now I can refer back to this article. 🙂