Frantic, frustrating, but often fun. Traffic management where you build the tracks.

Type: Single-player

Genre: Simulation, Management

Developer: Alexey Davydov,

Sergey Dvoynikov,

Timofey Shargorodskiy

Publisher: Flazm

Release date: Sep 16, 2015

Intro

A few years ago, I was looking for a game I could play with my then-3-year-old niece. She loved toy train sets, would play with them in the stores, and I’d pull out my old set we’d kept since I was very young for her to play with. Hence, I was looking for a train game that wouldn’t involve half an hour of construction and clean up between playing, and Train Valley looked like a cute, relaxing train set game. Well… at least the “sandbox mode” is like that. The actual game is not so much a creative tool as a mercilessly strict and sometimes outright unfair time and traffic management game.

Gameplay

Train Valley is not a game with any form of plot per se, but it is a game that uses various time periods around the world as a backdrop for its gameplay. There are four chapters (five with DLC) that have five regular missions each, with each chapter taking place in a different geographic area and each mission being a different time period. The third chapter, for example, is Russia, and its missions involve Tsarist Russia, early USSR, World War 2, Cold War, and the Space Race where you ship parts to assemble space rockets. The sixth mission of each chapter is a sort of bonus mission with more randomized elements, a longer timeframe, and no objective other than to make as much money as possible in the timeframe. Missions last a predetermined amount of time with the overarching goal of a mission is essentially just to not have negative cash on hand until the end of the mission, although each mission (besides the sixth missions of each chapter) has three bonus objectives for stamps.

The main gameplay involves having up to eight color-coded train stations which spawn trains with color-coded destinations. Each train also has a dollar value (always the same currency, regardless of the current chapter’s nation) for delivering it to its correct station, however, with every couple seconds that pass, the reward for each train drops, driving the player towards efficiency. This dropping price is no joke – even if you make a train depart the instant it spawns, the train will drop in value before it finishes even leaving the station it spawned in. Getting a train to even a close-by destination without at least three drops in value is basically impossible, so the nominal reward offered upon spawning a train is a pipe dream. The player also has to build all of the tracks that connect each station while managing a budget.

The way in which tracks work is the biggest departure from what I had expected going into this game; Maps are tiny, and often filled with bottlenecks like bridges whose locations you can’t choose that you have to build around. Whereas in games like Transport Tycoon Deluxe, you can easily set two “lanes” of traffic with one track for eastbound trains parallel to westbound trains, and use the stoplights on their tracks to avoid collisions, in Train Valley, space limitations and the raw cost of building tracks breaking your budget deny the ability to do anything that would make the game so easy. Instead, this is a game where the lay of the land often dictates only a few “right” ways of building your tracks, or you’ll have to restart the level. Basically, if you play train games to enjoy the creative freedom of building elaborate track layouts and scheduling departures to perfection then watching the system run itself, this isn’t your game. This is a game where once you’ve set the tracks down, you have to manually tell every train to depart, tell trains to stop or reverse if need be, pull every switch on the track to route the train properly yourself, and manage as many trains as possible at once to make as much money as possible. In short, it’s not a track-designing game, it’s a traffic management game.

Compounding this problem are two major issues: First, tracks can only turn 45 degrees per tile, meaning even a simple 180-degree turn takes a 4×2 area of the map. Stations placed close to each other can demand absurdly loopy routes to make connections. Second, tracks can only split in two directions in a single tile. This means a simple three-way intersection (where trains can enter from any direction and exit to any direction) requires a 3×2 area of the map and three switches, while a four-way intersection can take up a 5×3 or 4×4 area of the map, and require 6 switches. Allowing for omni-directional traffic means that even larger intersections, like five- or six-way intersections become geometrically more complex.

Like with many management games, the main objective is to avoid running out of money, however, few games are as capable of utterly blindsiding its players with game overs as Train Valley. During missions, new stations will open up, forcing players to connect the new station to the existing tracks, but while the game will prevent players from spending more money than they have on tracks, nothing warns them they’re spending almost all their money. A key feature is that you have an annual “tax” expense (presumably also abstracting other expenses), and failing to have money on hand to pay this means immediately losing a mission. It’s easy to spend nearly all your money building tracks, only to fail to have money on hand for taxes, especially when trains can take so long to reach their destinations that you might actually need two years’ worth of tax money on hand to survive. (Each mission takes place over decades, so game years last mere seconds, and trains can take several game months, or even over a game year to reach their destination.)

The game is pausable, which allows players to stop the game and issue emergency stop orders if trains might collide (but spot it quick – trains don’t stop on a dime, and even trains you ordered stop may still ram each other if there isn’t enough space to stop), or even reverse trains (engines teleport to the other side of the train) if need be, but in a sense, this seems to come at a cost. Because a game merely about managing traffic would be too easy if you could pause it at any moment to untangle any traffic knots, the developers instead decided to basically ramp up the difficulty of managing the budget to be nearly merciless in later levels, and force restarts for nearly any mistake. In other words, in exchange for having the ability to pause and give precision orders, the game demands absolute precision.

Everything about the game’s design, from the small maps, expensive tracks, forcing putting trains in opposing directions to share the same tracks, the dropping value of trains for every second that goes by, and annual expenses all push players to cram as many trains onto their tracks as tightly as possible in hopes of maximizing their profits. To do so, there is a button you can push to pay out more money to make another train spawn in the hopes of getting its reward so you can cram the tracks even more full of trains if you’re not yet sweating the default rate of train spawning. This is where the game’s real challenge kicks in, however, as you need to manage every train’s path by hand. If, for example, you have three trains in a row crossing a bridge connecting the east and west sides of the map, with the first going to the green station in the northeast, the second going to the grey station in the southeast, and the third going back to the green station in the northeast, you can’t just stop and only hit the switches to set a path that leads a train to its destination before it departs, you need to hit that switch between the first and second train going past that switch and then change the switch back before the third train gets there. When you have even more trains you need to manage in the background, even the best multi-tasker will eventually forget a switch and wonder why you suddenly have a train intended for the grey station suddenly being kicked back out of the purple station. Even worse than all this is that not all trains move at the same speed – you might be forced to repeatedly stop a bullet train that is behind a slower freight train when both are going in the same direction to prevent a rear-ending.

Beyond simply surviving to the end of a mission, however, each mission also has three objectives that give stamps for completing them to add some variety to the challenge. These can range from enforcement of things you would hopefully try to do anyway, such as avoiding collisions or sending trains to the wrong station or making at least a certain minimum amount of revenue, to restricting the number of existing objects like trees or houses that you can demolish to build your tracks, further restricting your building space, to demanding you never stop or reverse a train or demolish any piece of track you have built. With high-speed trains in later levels, even seemingly simple objectives like avoiding allowing a train to reach the wrong station can force you to restart a mission you’d nearly completed.

Luck-based missions

While the game manages to generally be “tough but fair”, there are several key aspects of the game that are downright unfair.

First, while you are often under tight budget restraints, the actual rewards you get from making trains reach their destinations is blindly random, with no regard for distance to travel, length of train (and trains don’t pay out until after every car reaches the destination, so on such short maps, long trains add significant distance to destination and are a further roadblock to snarl traffic), speed of train, or any other factor. Laying down initial tracks can nearly bankrupt you, and it’s entirely possible that the first one or two trains’ random rewards just won’t cover expenses at the end of the year, forcing restarts until you get lucky with the money the Random Number God deigns to give you this run.

Second, compounding the first, is that while you can try to make more money by summoning new trains to try to get their rewards, this has a cost. It’s entirely possible for summoning a train to cost $1000, but for the initial reward for the train to be $800 or less. (And remember, you never get that maximum reward.) It’s also possible the train would be worth $5000 and pay for two years’ operating expenses, but that’s all up to the whims of the Random Number God. In maps where you need to pay for connecting new stations early, before you can build up much cash to pay for those connections, trying to ram through as many extra summoned trains as you can to build up cash early is the only way to survive, but when the RNG smites you, there’s no hope for success but to restart and restart again until it deigns to give you its blessing.

Finally, the sixth mission of every chapter is a more open and randomized map, with all the problems of “no sanity checks” that all the other randomized elements of this game has. The stations appear in fixed positions, but in random order, so it’s powerfully advantageous to have stations near each other. In fact, it can be impossible to connect stations on opposite ends of the maps with some of the missions’ starting funds, so you outright need to restart until you get nearby stations. Worse, the game adds obstacles in randomized locations, and these obstacles can appear in key chokepoints that block off the ability to make a key connection. Restart and restart again. Then, these maps are subject to the same problems of demanding you pay to summon trains that may not even cover their summoning costs. Restart and restart and restart again until they do. What makes it so bad is that these are the maps meant to be the replayable challenge maps, where you try to maximize your total money, and once you get going, it’s just a matter of trying to maximize a fat cash flow… but each time you want to start, it takes dozens of restarts, until you’re just not interested in playing anymore to get a map where you can even try to challenge your old score.

Graphics and Sound

Train Valley’s minimalist art style manages to be fairly cute. There isn’t much detail, although there’s more than in Train Valley 2, but what’s there is attractive, yet utilitarian. You can zoom in to see how little detail there is, but while actually playing the game, there’s basically no reason to have the map at anything but zoomed out as far as it goes. Zooming in is for screenshots.

The game’s music is… well, mostly stereotypical. When playing the Russia levels, there’s exactly the sort of horn-heavy “USSR music” you’d expect. Japan levels have kotos playing. With the Germany DLC, there’s oompah band music playing while bombs fall during the World War 1 mission. Only the Europe and America levels have music that doesn’t sound stereotypical of their respective nations, and that’s because it’s almost purely generic. There’s a soundtrack DLC, but I’m not sure why; It’s forgettable background music that serves its purpose of reminding you this mission is set in Russia during the Cold War or whatever, and that’s all. That’s not to say it’s bad music, it’s just generic mood-setting music.

Interface

Here’s where I have a few troubles. The game features fairly small buttons, and a major part is to make trains go from starting stations, which are eight colors of circles, to destination stations, which are the same eight colors of slightly smaller squares. Visually, stations are identical except for the big circle above them; The roof on a station is no indication of which colored station it is, and the square destination icons can overlap with the circle station icons. I’ve had several accidents that forced restarts because I was confused by icons obfuscating which station is which. God help you if you’re color blind – the icons have little pictures on them, but they’re faint, icons can overlap making things worse, and every button has the same shape, making things worse. There is a colorblind mode, but it just replaces the pictures with letters that are still have too little contrast to be clearly legible in a timely manner, which is pretty crucial in a time management game.

Also, these icons are small. The game has a few hotkeys, but the most important parts (besides “pause”) are all clicking on the icons. If you don’t pause, having accuracy in clicking on specific track switches or train icons to stop them is vital to avoid accidents. Even for myself, I set the interface to its maximum size (all screenshots besides the one immediately below are with interface size cranked to maximum), and found it small. My niece, who still couldn’t use a mouse very well, found it very difficult to click on icons. When I brought it up in the forums, I was told to set the interface to maximum size in the options, but I already had, and even at maximum size, it was terribly small. Setting the game to the smallest interface scale is almost farcical – it’s almost impossible to read, much less click on anything when they’re moving targets.

Germany DLC

The only non-soundtrack DLC for Train Valley is the Germany DLC. Aside from the second mission – set during World War 1 – having biplanes drop bombs on your tracks at random times, the missions are largely just more of the same in the base game. As I previously said, however, there’s not much reason to replay missions, so if you liked the game you’ve already played, then the DLC offers 25% more content for an additional 25% of the price of the base game. In essence, it’s something you shouldn’t fret over buying until after you have completed the base game and decide whether you still want to play more of the same game.

Verdict

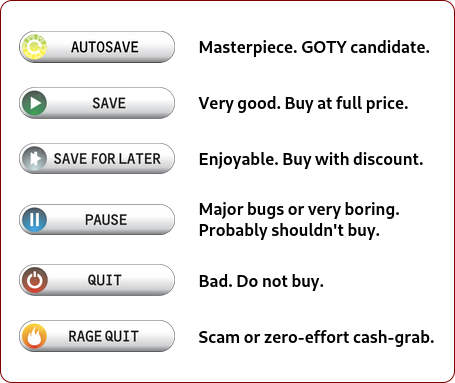

Train Valley wasn’t what I initially expected, and I had quite a few frustrations with it. However, especially in comparison to its sequel, these frustrations tend to make you want to play the game just to beat the sucker, and even though most of the problems with the first game were “fixed” in Train Valley 2, it’s pretty telling that I played Train Valley (1) to 100% completion (including the DLC), while Train Valley 2 just never hooked me, and I stopped after about 5 levels.

That said, completing the levels is basically all your drive. Outside of the sixth mission in every chapter being a “score as much money as possible before the end of the mission”, few levels give any reason to repeat them after you have three stamps.

As for giving kids a toy to play within sandbox mode, my niece could generally play it for about 15 minutes before getting bored, making some trains collide on purpose to watch the explosion, and then going on to do something else. Compared to other toys she’s discarded, the price of this game and the number of times I could get her to play it still made it a relatively good value.

This is a game that has a definite “shelf-life”, in that you basically play through its content, then you’re done with it forever (unless getting kids to play sandbox mode), but it’s also a game that is inexpensive even at full price, so especially on sale, I can recommend this game as being a good change-of-pace game. It isn’t as heady as most manager games I play, and it certainly demands near-flawless play from its players, but it stays basically exactly as long as it’s welcome.