Roll with it.

Type: Single-player

Genre: Puzzle

Developer: increpare games

Publisher: increpare games

Release date: 16 April, 2016

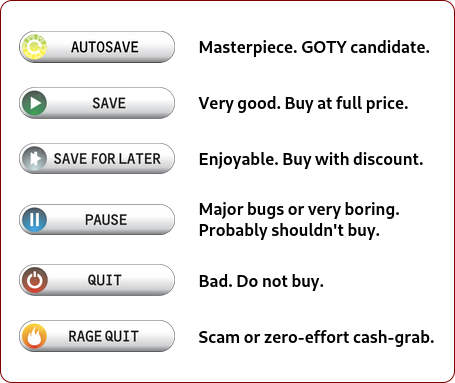

Sometimes the diamond-in-the-rough narrative gets overplayed on Steam, yet given how exceptional of a game is here hiding behind a deceptively simple store page this game warrants its fame. Whether or not the developer intended this outcome, it’s somewhat appropriate for a puzzle game for diehards to use its vagueness of a description and its price barrier as deterrents to outsiders. As the old saying goes, “Laws are like sausages. It’s better not to see them being made. To retain respect for sausages and laws, one must not watch them in the making.” To people who do desire to see through the muck to see how principles come through solving problems, Stephen’s Sausage Roll may be up there with The Witness as one of the best puzzle games available.

Those Who Think They Know How the Sausage Rolls Do Not Yet Know As They Should

Obfuscation is the metaphorical bread-and-butter of Stephen Sausage Roll, so explaining anything in detail will somewhat influence your experience; however, it is possible to know what type of experience you’re stepping into by discussing the game as a whole. Stephen Sausage Roll uses the entire game for its mechanics, leaving nothing nor asset unused from its world, Stephen and its many sausages. The whole package continues being iterative, adding new dimensions to previously learned skills that aren’t technically new abilities as you don’t earn them arbitrarily but rather through realizing you had these tools all along until you discovered them from experimentation. Similar to The Witness, you create new observations as you play that become tested principles, which continue to establish new hypotheses as applying these principles to a new context is half the challenge.

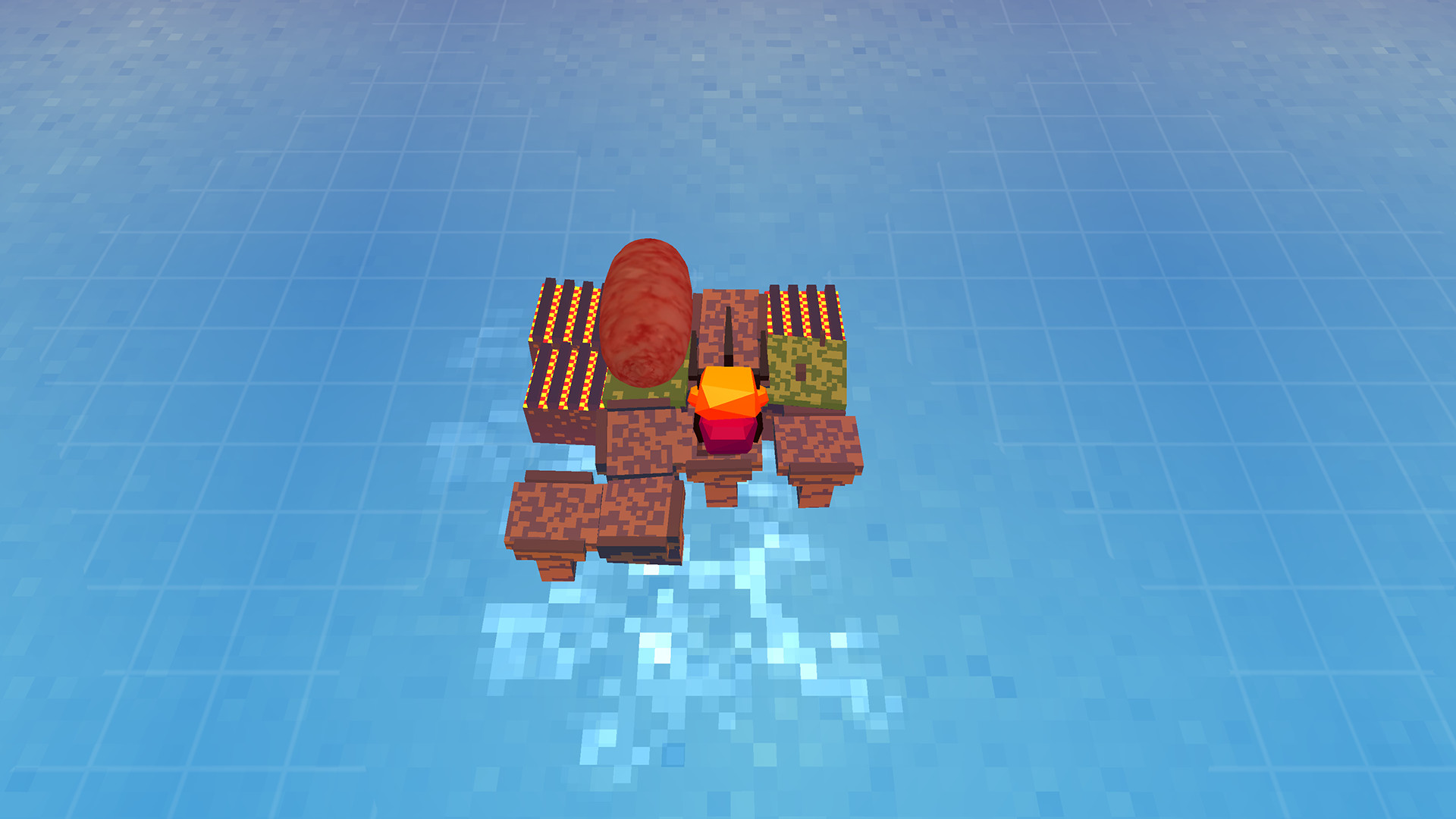

At the game’s core mechanic, the goal is to cook both sides of every sausage without burning them. Stephen comes equipped with a fork, which provides the first major hindrance, the control scheme. These controls are not bad nor broken; they are deliberately unintuitive to force you to think ahead of your next move. The best description is to imagine tank-controls where you can move forward and back given the direction of your fork, and the orientation of your movement changes when the fork is rotated clockwise or counter-clockwise. Many of the puzzles force the player to deal with the awkward controls, as navigation on the overworld takes time to adjust to them. After becoming accustomed to moving backwards more than moving forward, the game changes the focus onto the sausages and Stephen’s fork as every new island builds on those controls.

Repetition breeds familiarity, and there are always new techniques between each puzzle to further expand the existing knowledge you may or may not have about the puzzles. As you play, the problems with the controls become less apparent as rolling sausages and manipulating them to new heights become more urgent matters to learn. There is only one mechanic with the fork that becomes forgotten, and it feels more like an oversight not to make the game too difficult towards the finale. As a result, everything you master truly feels like an achievement as most challenges will leave you perplexed until that moment where everything clicks together brings a sense of clarity.

When the World Comes to an End, What Idea Will You Leave Behind?

Similar to The Witness, the open-ended world design and the narrative are blended seamlessly with the types of puzzles in the area in the large scale. The major differences between Stephen’s Sausage Roll and The Witness are that the narrative, however of a morsel it may be, is more satisfying despite being extremely simple and the worlds’ puzzles are more disjointed from the narrative texts. These aspects highlight a problem, especially with the spikes in difficulty, of not properly scaffolding information necessary for the player to get the idea.

Scaffolding is a common educational technique to pre-engage audiences in advance by transitioning from something more familiar to something entirely different with ease. In layman’s terms, it’s the process by introducing something old to teach you something new. Stephen’s Sausage Roll takes a similar idea from The Witness by breaking up the overworld into six regions, each emphasizing a new skill; however, unlike The Witness, the puzzle between each island meant to clue players into the next area’s challenge doesn’t always convey the correct expectations. For example, the bridge from the first two worlds does not prepare you for the first major challenge, The Tower, which suddenly reconfigures the puzzles in terms of height. The Witness always managed to achieve this goal with physical gateways to guide players to the next proper area. Only with the final island does Stephen’s Sausage Roll set the correct expectation that becomes the basis of the final twenty or so puzzles, which is what makes all the difference between needing hints or figuring things on your own.

What the game does let you discover all on your own, perhaps with more interpretations than definitive answers, is the narrative behind the world. Interspersed throughout the lands are bits of lore to tell you of the society that came before you, presumably Stephen. The reasons for the disappearance of this former world are given some answers, namely the massive flooding around the world which surrounds you, yet it never tells you how that disaster came to be. Natural disaster by the whims of fate? Climate change by man’s influence? All you are given are glimpses of what wonders are left and what knowledge is left preserved on these floating islands out at sea, only those relics and a vague notion of some idea worth saving are the last vestiges of this world. The answers to these questions are treated with subtlety and meant to be open-ended for the player, which is the difference between players making their own answers and dismissing any value in meaning.

Verdict: Fortune Cookie from Lo Wang says, “What You Saw, Sages, is the Wurst of Man”

As interesting as the narrative was to piece together, there is no definitive higher meaning to attribute the lessons from the game as some clever allegory. Perhaps it’s the result from one too many Wang jokes, but call it intuition that a game about rolling sausages is not searching for something revolutionary about the world. The real core value and the real pleasure about Stephen’s Sausage Roll comes from the process of learning from the puzzles themselves. Savoring them as a delicacy, even when they are too tough or too soft, is to appreciate how appetizing they are whether at the start or the end of the day to keep your mind proactive, and you certainly don’t want to be the only one missing out from experiencing the game for yourself. Buy several copies and share them with your friends; after all, the last person left will be all alone to fend for themselves, and wouldn’t that be such a waste?