Cracked Heads studio makes their debut with a survival-horror game that looks pretty, but chooses cheap jump-scares and scavenger hunt mechanics over more interesting, thoughtful, and immersive choices.

Released: Steam

Type: Single-player

Genre: Survival-Horror

Developer: Cracked Heads

Publisher: Headup Games

Release date: 6 August, 2019

Standing On The Shoulders Of Giants

Silver Chains, and indeed the survival-horror genre in general, owes much to the 1992 title Alone In The Dark. Released for the PC by Infogrames in 1992, Alone In The Dark puts the player in charge of the intrepid paranormal detective Edward Carnby, in a fantastic, puzzle-driven adventure set in a mysterious, haunted mansion. The original game was mostly a bloodless affair, chocked full of head-scratching puzzles and curious clues. And while the player could eventually acquire a few meager weapons to defend against some of the monsters later in the game, quite often a less violent solution that involved wits, critical thinking skills and an array of movable props would suffice.

In one particular instance, a demonic creature bursts through a window into the room the player is occupying. Early in the game, Edward Carnby doesn’t possess any weapons or other means to directly kill the creature. The solution? Push a tall armoire in front of the window, and block the demon’s entrance altogether. Violent? No. But creative? Absolutely.

That sort of gameplay revealed Alone In The Dark to be a thoughtful, smart and inventive puzzle/adventure game. It set the bar for all haunted-house games to follow. In 1994, two full years after its release, PC Gamer dubbed Alone In The Dark one of the 10 best PC games ever made. Despite its primitive graphics and awkward use of static camera angles, it stood out as a prime example of what a survival-horror/haunted-house game could, and should, be.

Silver Chains shares a good bit of DNA with the old Edward Carnby adventures. A haunted house. A lone protagonist. A mystery to solve. Clues to find. It’s definitely traveling down the same dark and eerie road that Alone In The Dark forged over twenty-five years ago. The setting is good, the mood is right. Everything is in place for a good romp through a haunted mansion.

It Was A Dark And Stormy Night

The game begins as you, a young Englishman named “Peter”, find yourself stranded in the middle of a darkened, fence-lined dirt road. Your 1920’s era automobile has slammed into a tree; its headlights dim, engine steaming and finished. Faint moonlight slips past a canopy of trees flanking both sides of the road that create an oppressive and dark tunnel toward an old, possibly abandon, manor. There’s only one way to go and one obvious choice to make: walk toward the house. Maybe help can be found there?

As setups go, the beginning of Silver Chains is fine. It’s appropriate. It’s what we’d expect from a genre game like this. We know what we’re getting into, and we’re happy to wander down the road to the foreboding house at the end of the lane, where a lone silhouette occupies a lamp-lit window. We watch as it blinks out and we think we know what to expect. Puzzles. Scares. Maybe more puzzles. It’s a haunted-house survival-horror game, after all. What could go wrong?

But the opening scene for Silver Chains reveals two of its central weaknesses. First, it’s a fairly linear game. But worse, it’s simplistic. Pressing a single key on the keyboard (or button on a controller) and watching as the screen lurches forward down the dark path, one footstep after another, with nowhere else to turn and nothing else to do, is a pretty good metaphor for the type of gameplay the player will experience for the remainder of their time.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing if all the other elements of the game are done well. Simple and linear can be fine, if there’s a compelling narrative to drive the player forward and the progression through the story is interesting and fun. But Silver Chains hurts itself with a number of missteps. It feels like watching a promising sprinter stumble out of the blocks with untied shoelaces, never to recover, eventually falling down and skinning their knees.

Barriers, Barriers Everywhere & Not Enough To Make You Think

One of the game’s primary issues is the overuse of artificial barriers within the mansion as a device to guide the player along like a cattle chute.

In the early game, especially, there’s often only one way to go and advancement is simply a matter of the player finding and interacting with the appropriate prop. Read a note, pickup a key, find a photo. This is made even less interesting by the fact that nothing else in the game can be manipulated by the player; just the props that trigger advancement. There are no red herrings, no misdirection at work. There is literally nothing for the player to contemplate in the game. The game play is as simple as it gets. Find the next clickable item and advance the story. Turning a page in a book is about as difficult.

The mansion is replete with artificial barriers that exist for no other reason than simply because the plot requires them to. In one example, for instance, the player cannot enter a room because it’s dark. Yes, because it is literally dark. This seems a bit odd, especially considering the door to the room is open. Not being able to walk across the threshold because it’s dark is a puzzling design decision (I get what they were going for here – they want you to find a lamp to use as a light source first – but this was a poor way to handle it). It’s not until the player finds the lamp that they can finally enter the room and look around. Why the player isn’t allowed to wander around the room and stumble about in the dark, even if it is a fruitless endeavor, remains a mystery. Banging your head against a wall in a dark room, unable to manipulate any props, would have worked just as effectively to prod the player to find the light source, and it would have been more immersive too.

Later on, when more of the house opens up and the player is free to traverse the three main levels using the staircases, many of the doors still, perplexingly, remain locked or barricaded. Some locked doors have a hot-spot, and pressing the “E” key will cause the door to rattle, but not open. Does it require a key to open? Or a plot point? It’s unknown to the player, and not always clear. Other doors have no hot-spot at all, which means the door is somehow barricaded by an obstacle on the other side: a fallen bookshelf, a chair, or nailed-up boards. This is where the lack of interactivity hurts the game. The player can’t move the chair out of the way if they find themselves on the other side of the door; they cannot push the bookcase out of the way, or remove the nailed boards either. The doors remain blocked for the duration. Imagine being able to move these objects out of the way and really open up the house? It could have provided the player with even the smallest sense of achievement; it could have made the player feel like they were getting somewhere.

A Mystery Wrapped Inside An Enigma Wrapped Inside A… Never Mind

The other chief issue with the game is its puzzles. Or more to the point, the lack thereof. The haunted-house genre has been around for a long time, and puzzles are a huge part of their allure. The key to deciphering such puzzles is often stitched deeply into the game’s narrative, which makes uncovering the mystery all the more important and impactful to the player. Learn something about the events that happened in the house, and you’re likely to solve the next puzzle blocking your path. However, Silver Chains doesn’t seem to understand this, or they simply eschew such mechanics in favor of something that feels more like puzzle-lite. It’s a half-measure, if that.

Part of solving puzzles in any haunted-house game requires the acquisition of props; finding the right item for use at the right time. Find a key to open a box; find part of a broken light fixture and then use it to repair the fixture, thus opening a door. That sort of thing. But the problem is, that’s all Silver Chains knows how to do. Hide props. Nothing else. There are no head-scratching puzzles that require narrative knowledge in order to solve.

Oh, there are a couple “puzzles”, if one wants to get technical. But the developers seem like they’re either afraid to trust the intelligence of their audience to figure things out, or they don’t understand how to tie their narrative together with creative puzzles.

For instance, there’s a spinning lamp in the game that projects stars and various other celestial images onto the walls of a room. It’s a visually interesting scene and is the perfect setup for a narrative-driven puzzle. I initially thought that maybe a specific star had to be projected at a certain point in the room, on one of the walls maybe, and thus it might cause something else to click into place, or open up. Guessing what purpose the light served seemed futile, but I thought surely the narrative of the story would inform me of exactly how to use it and save me the trouble of guessing.

But no.

Instead of creatively using the narrative to instruct the player on the purpose of the spinning lamp, the developers put the solution on a wall and treat the player like a kindergartner sitting in front of a chalkboard. The solution to the “puzzle” is to treat the lamp like a padlock, spinning it left and right a certain number of times, and the game just hands out the combination like it’s the first day of class. No narrative connection at all. So here it is, on a whiteboard. Write it down kids, and don’t forget it.

The World From A Different View

Later on in the game the player finds a monocle. This becomes another example of the developers setting up something really interesting and creative, and then not using it to its full potential.

Wearing the monocle changes the player’s vision, allowing them to see hidden signs inside the mansion. It’s a neat idea, but the developers don’t do anything creative with it. The whiteboard gives the player the “clue” about where to walk once they find the glyph, and then the player simply uses the monocle to find the hidden signpost, walk the appropriate steps, and open a door. Or in my case, feel frustrated because I did precisely what the game asked me to do, and the door didn’t open. This seemed to be a bug in the game which was only overcome when a different, unrelated door elsewhere in the mansion, finally opened as well.

Can You Save Me From Myself?

Another issue the game has is its annoying reliance on an automatic checkpoint-style save system. This is a common mechanic in console games like Gears of War, where the developers want to control the size and number of save files, due to limitations on hard disk space. This is understandable. It’s also, still, to this day, a terrible game mechanic, because if a player cannot advance forward enough to find the next checkpoint, they are forced to replay several minutes of the game all over, for no reason other than the game lacks a proper save capability. Silver Chains was built on the Unreal engine. There’s simply no reason a first-person game of this nature, on this engine, cannot properly save whenever the player wants. Sure, go ahead and limit the player to a single save file. But at least let us save whenever we want (or at least during any part of the game that isn’t scripted).

May It Be A Light For You In Dark Places

If there’s a saving grace for the game, it is the visuals, and the mansion itself. Atmosphere is a huge part of the survival-horror genre, and Silver Chains does this part very well. The setting is good; the house is fairly well rendered. The decrepit mansion is properly eerie, with just enough creepy odds and ends scattered about to set the mood and prep the player’s expectations. The house is easily the best part of the game. The developers, rightfully, go for a realistic aesthetic here. The mansion feels like it was a real place at one time, with functional rooms, like kitchens and bathrooms, in the right locations, where you would expect to find them. At the same time, Cracked Heads has done a great job building a properly labyrinthine structure which has just enough character to confuse the player. It takes a little bit of time to get a real foothold on the layout of the house.

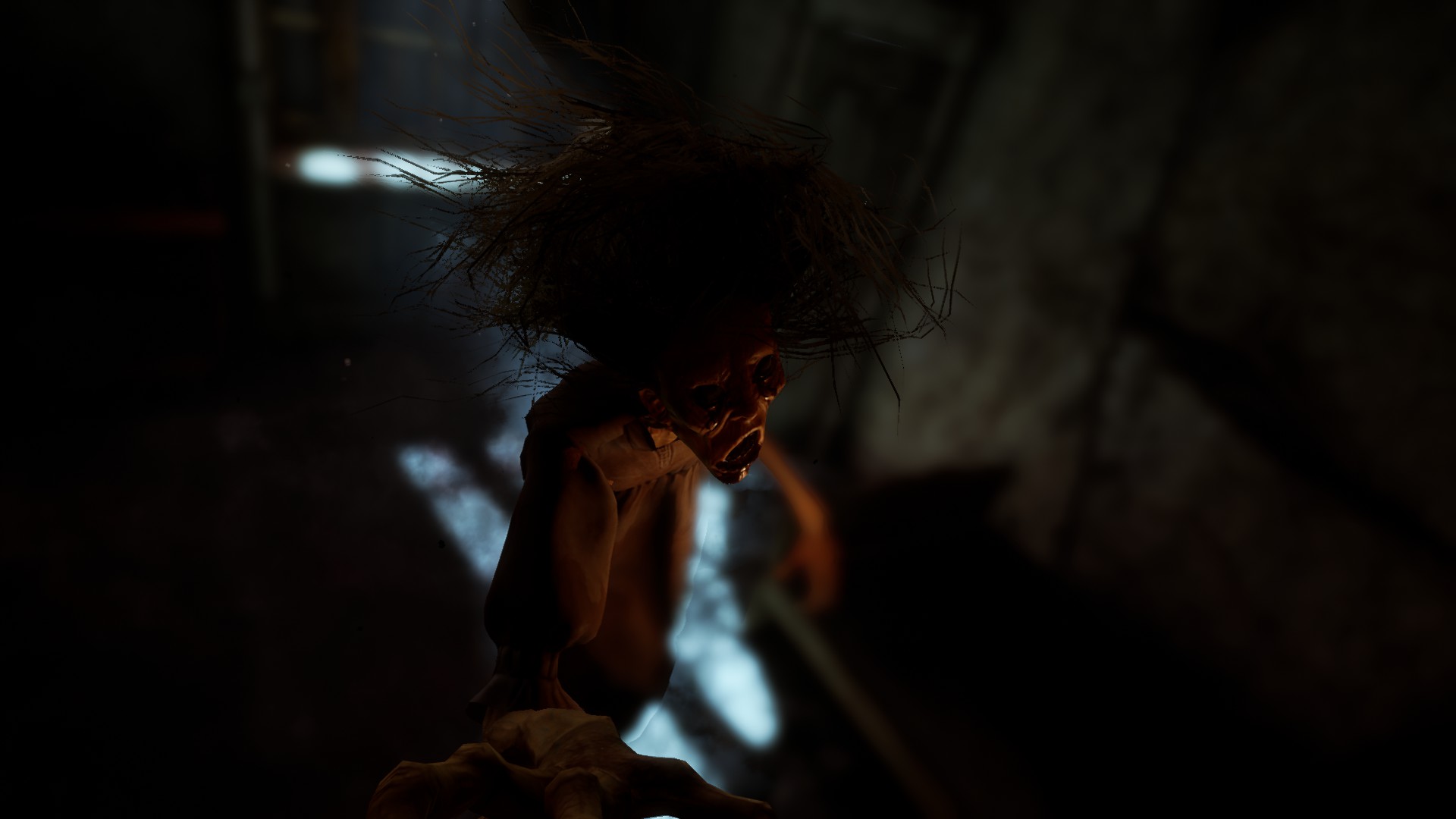

One of the better moments inside the house, and a good use of foreshadowing, happens early in the game when the player encounters a wardrobe they can interact with (sadly this is one of the only pieces of furniture that can be manipulated). The text on the door handle gives the player a clue when it reads “Hide”. Touching the handle causes the player to hop inside and close the door to the wardrobe, leaving only a small crack for the player to look out from. The necessity for this mechanic becomes apparent a few scenes later. And this ends up being one of the stronger elements of the game – hiding from the antagonist in the story.

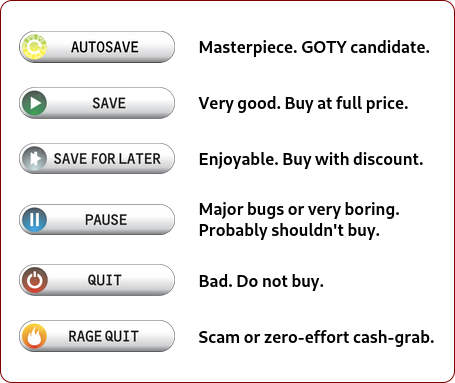

I don’t feel like I’m giving too much away by saying the game has a creepy “monster” in it that, at various points, tries to attack you. The use of the wardrobe as a means to hide from the creature is creative and immersive. But this mechanic seems under-utilized as a method for adding tension. Later in the game, when the mansion opens up a bit more, and the player is able to start roaming the various levels and rooms more freely, the presence of the wardrobes, and the potential appearance of the creature, could create a fair bit of tension. And the game even tries to set this up by having the protagonist announce aloud that they will have to be more quiet if they expect to get out of the house alive. But it doesn’t take the player long to realize this is a lie; the monster is scripted for specific moments, and will only appear at those times. And when it does, there will just happen to be a wardrobe close by, as necessary.

This is another example of a missed opportunity in the game. Imagine if the creature could show up any time, potentially triggered by the player’s footsteps? Or if overuse of the lamplight would cause to appear? How terrifying would that be? That would immediately ratchet up the tension with every step. Imagine if your footsteps actually caused a higher chance of the creature showing up? Imagine if running guaranteed its appearance? It would become incumbent upon the player to memorize the locations of the wardrobes (maybe even have, or create, a map) and know where the closest one was at all times. Sneaking, which is allowed in the game, would become paramount, as would judicious use of the light.

Now imagine if the player could physically remove the obstacles blocking the barricaded doors, to create quick access to nearby wardrobes. The player could be actively working to make their situation better, so that they could increase their chance of success in figuring out the mystery of the house and escaping alive. Suddenly, there’s a much more interesting game with a more palpable tension to it.

But the developers never go this route, and indeed, seem like they never even considered it. The lack of interaction with the house makes the whole space feel flat and uninteresting. It’s a pretty picture. But that’s all it is; it’s just a pretty picture, and not much more.

Boo!

Like other survival-horror games of the genre, Silver Chains doesn’t shy away from a good jump scare. And to their credit, the jump-scares here are effective. They even got me a couple times, and I’m not easily scared by such tactics in films or games. But unfortunately, this seems to be the only card the developers know how to play; it’s their lone trick (albeit a good one) for manipulating the player’s emotional state. Which is a shame, considering they’ve put together a fairly eerie and labyrinthine house to explore.

There’s A Story In Here… Somewhere

A lot of these weaker elements could have been strengthened if the overarching narrative of the game was tied into the gameplay. That’s really the biggest problem with Silver Chains: there’s no connective tissue, and the narrative is supposed to be that tissue.

Puzzles don’t really exist, and the ones that do have no connection to the narrative. The story itself is doled out through a series of found correspondence that are, to put it kindly, not well-written. Using old letters or journal pages to tell a story is a common mechanic in games, and sometimes it actually works (think System Shock). But here, it just feels ham-handed. And again, it feels like the developers don’t trust their audience to be smart enough to piece things together themselves.

In addition, the protagonist comments on every piece of correspondence that is found. The protagonist’s comments are actually quite a bit more insightful than the letters themselves. The game would have been better off, as it is currently constructed, if it had not provided the letters at all. Just tell the story visually, and let the protagonist comment as they progress. That would have worked much better. After all, there’s not much of a story here to begin with. A few musings from the protagonist would have been all that was needed to explain the narrative.

She’s Got The Looks That Kill

The graphics are decent. I don’t want to say amazing, because they aren’t. Games like Fallout 4 and Skyrim, played with ENB installed and all graphics options set to ultra, still look better on my TI 1080 than Silver Chains did out-of-the-box. What’s ironic is that a quick perusal of the Cracked Heads Twitter feed shows screenshots that actually do look amazing; as if they were rendered with an ENB on a RTX 2080 card. So it’s difficult to say what the game might actually look like if one had the very best hardware currently available. Maybe the graphics can look amazing if you have the horses. But I found it surprising that I wasn’t blown away by the visuals, especially the textures, considering the artistic quality of the game stood to be one of the most important aspects of it, especially taking into account the genre.

It Is The Sound… Of Silence

Sound is a different matter. It’s very hit-or-miss.

The score is sparse, but well done, and performs its function well when required by certain scripted sequences. But the sound effects are a different story. Some of the sound effects are well done and do a good job putting the player in the moment. For example, footsteps as you walk; doors as they open; the floor creaking; the brass lantern screeching as the player turns it on or off; these are all fairly well done.

But other sound effects are quite bad and break the immersion. The chief culprit here is the thunder. There’s a storm happening outside the manor, and periodically the player will be reminded of it. Unfortunately, the thunder sounds terrible in this game. The start of a thunder roll sounds a bit like your foot catching a sandbag in Fallout 4 (and indeed, I looked down at my character’s feet the first time it happened, wondering what I had just walked into). This is a bit perplexing, considering there are free mods for games like Fallout 4, such as TrueStorms, that have excellent thunder and lightning sound effects in them. It’s a bit startling when a newer game is released with sub-par sound effects, and yet mod authors for older games have been releasing top-quality work for years, often for free. One has to wonder, in this industry, how does this happen?

User Interface

As for the interface, it is clean and unobtrusive. So clean, in fact, that one of the first things a new player will want to do is open up the options and check the Control settings, to get an idea of what functions are available in the game, and which keys perform them. There are portions of the menu system that are not entirely intuitive, however, especially taking into account modern UI paradigms. The graphics settings screen, for example, is initially quite troublesome. For instance, there’s no way to set all graphics options at once using a global command like “High” or “Ultra”, as is typical of most modern games. Instead, the player must click on individual labels, and then adjust a slider. And it’s not immediately evident which slider belongs to which option, or why all the sliders are visible on the screen when a specific graphics option is selected. The whole layout of the graphics options screen seems like it was designed by someone who had never played a PC video game before.

The rest of the interface, however, is done well. It is stripped down, simple, with big fonts that are easy to read. Key re-mapping is provided, which is probably the biggest feature that seems necessary.

Verdict

I was a big fan of the first Alone In The Dark game when it was released in 1992. I enjoyed finding the critical props and working out the puzzles so I could progress to the next area of the haunted mansion. This was before the rise of Google, so there weren’t a lot of resources if one got stuck. You just had to keep trying different approaches. Sure, the game had a very clunky interface, and it definitely was a linear game experience, but the puzzles and story were so good that they transcended the game’s deficiencies.

I was really hoping Silver Chains was going to be a modern spin on the haunted-house genre that would surpass Alone In The Dark. After all, I’m kind of a sucker for a good haunted house story. And video games have come a long way. They can allow for a lot more world interaction, which potentially could allow for a much more tightly coupled narrative.

But Silver Chains never goes that route, and as a result, it never gets to where it needs to go. It sets itself up nicely: good atmosphere and aesthetics, jump-scares that properly frighten, an eerie house that has character. But it just can’t deliver. It’s little more than an interactive film; it is a brief game of missed opportunities and thin game mechanics. I would only recommend this title to people who absolutely love the haunted-house genre, and then I might even hedge my recommendation a bit (given its very brief length) and say: wait for a sale.

Hey ColorsFade, Another good honest review. Sounds like this game could do with a shot at Early Access for more interactive content and polish. I am curious as to what it would look like on my 2060 RTX, but not at the price asked.

Arpeggio