How far can you suspend your disbelief until a NPC/AI can appear human? OneShot puts you to that test.

Type: Single-player

Genre: Adventure, Casual

Developer: Little Cat Feet

Publisher: Degica

Release date: 08 Dec, 2016

Meta-games, by their nature, are spoiled when you know more than what you should know going into them, and OneShot is no different. However, like other similar games such as The Stanley Parable, Undertale or Pony Island, it really doesn’t matter whether you have any expectations or none; the experience is still worthwhile to play it for yourself. Even if you think you may be worn out by these meta-narratives, OneShot offers some refreshing ideas that is all the better to discover on your own.

Spoiler Free Recommendation: Try the Freeware Version

Unfortunately for review purposes, it’s impossible to critique these games without some spoilers that may ruin the experience. Instead of suggesting you should buy a game without any expectations while at risk of not liking it within the two-hour refund window, I would suggest you download the original from 2014. It’s freeware; it takes an hour to complete; and even the puzzles, while similar, do not ruin the surprises in store if you were to go into the remake without a clue.

People who lambaste OneShot for being in the shadow of Undertale are being ignorant; they do not realize this is a remake fit for a full-purchase similar to Cave Story+ and The Stanley Parable. When people criticize the lack of originality with shared ideas, these people put too much emphasis on originality rather than realizing ideas can be arrived at by different people at different times; the execution is what matters the most. If you are concerned there is not enough content compared to the freeware version, rest assured that OneShot adds not only an amazing amount of polish and technical improvements but also the game and story have been given new content to make it unique.

If you do intend to play the freeware version, you should know that the remake fixes a lot of RPGMaker(2003) technical issues. Besides the new content, the remake does not suffer the limitations of RPGMaker by its UI, the lack of full-screen and any control bindings, nor does the game punish you if you close the game in the wrong place. The only risk you have for trying it is that you’ll have to replay the same content when you purchase it, but there are moments within the final release to let you bypass the explanations of puzzles the second time around.

The Element of Surprise is Boredom

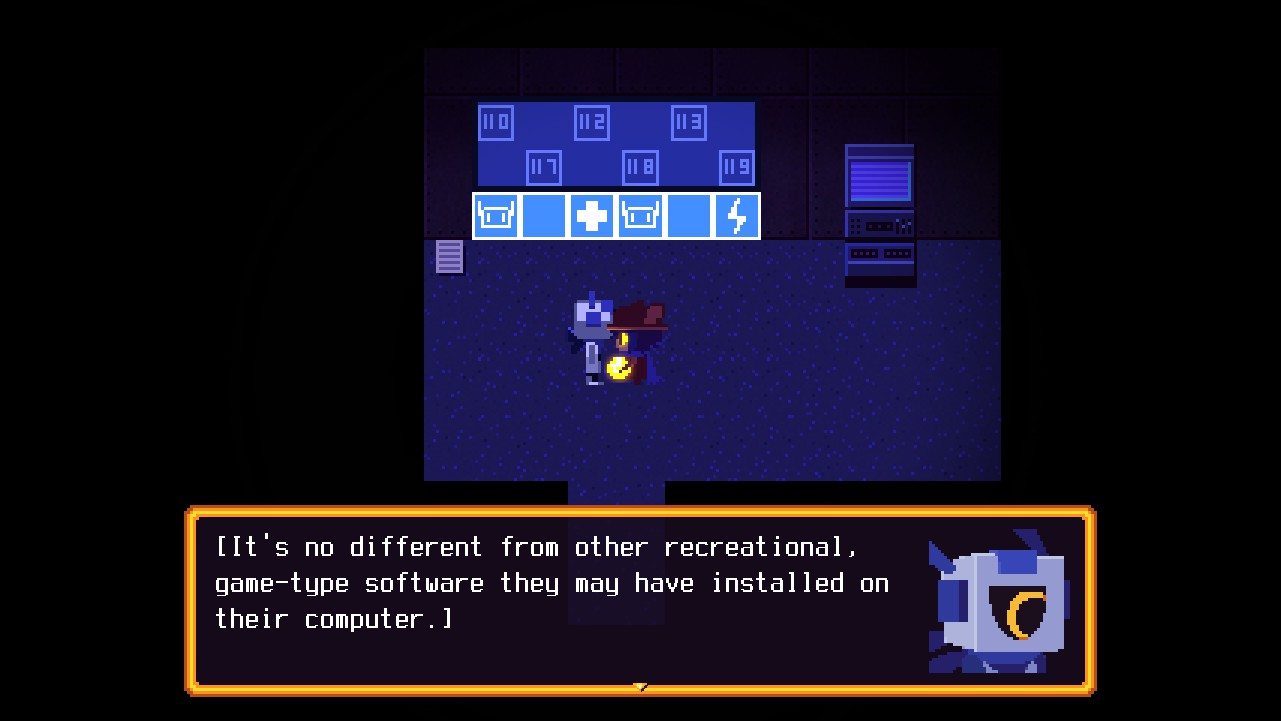

As you might expect with a game originally designed from RPGMaker, the gameplay is a simplified adventure-game with puzzles reliant on collecting objects and rubbing them on objects to progress the narrative. There is more to OneShot than a great narrative behind the bog-standard gameplay; however, revealing what that is cannot be done without ruining the surprise, so let’s call this content meta-puzzles. Unfortunately, when it comes to these meta-games, OneShot suffers more than its competitors by relying too much on its meta-puzzles as well as its strong narrative rather than the core gameplay to keep players engaged.

This isn’t to say OneShot is padded as the adventure-game puzzles pace out the meta-puzzles from overstaying their welcome. The simple truth is the overall gameplay is not as interesting as the non-combat system of Undertale nor the choices and consequences of The Stanley Parable. However meaningful are the boring puzzles to the narrative, these drags in the story may keep some people from finishing the game if your expectations aren’t set accordingly. If you enjoy the appeal of interacting with NPCs in RPGs, exploring lush environments and reading flavor-text in the absurdist style of Earthbound, then you’ll enjoy the experience as well as revel in exploring the idea of a “Fifth Wall” of storytelling.

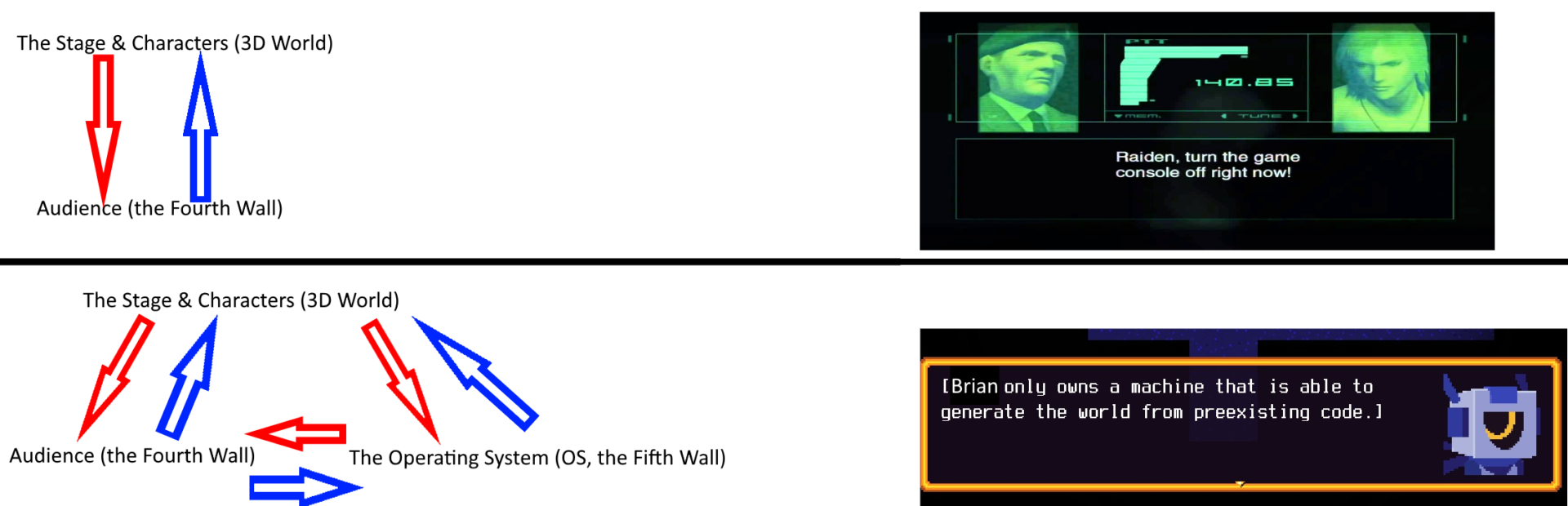

What is the ”Fifth Wall” of storytelling? It’s a subtle deviation from what is viewed as breaking the fourth wall with the key difference being that there is a “real” audience (the player) as well as a fictional audience (your computer itself) in the story. This is not a misunderstanding created between the real audience and the characters seeing one-another as unreal like god. The audience-in-the-middle is as much as a character as the real audience, and both are distinct characters in the role of the story.

For those not familiar with the fourth-wall, breaking the fourth wall is when characters in a story address the audience. Jokes at the expense of the illusion of fiction; self-aware comments at the tropes or the expectations of a genre; turning conventions of a medium on its head for examination with a wink. All these aspects are meta-commentary on the work of art and the expectations of art, and it’s what people enjoy discussing when they think about what makes Deadpooland any character by James Joyce equally compelling. (What? Can’t someone enjoy both without sounding pretentious?)

In terms of games, The Stanley Parable is the best demonstration of the conflict of fourth-wall storytelling: The Narrator/Author, the Character (Stanley) and the Player. The tug-of-war of agency between each performer creates the jokes and the “unintended” consequences of your choices. The reality, however, is every new dialogue and quip you unlock is another moment where the other actors pretend to be surprised by an outcome that was already considered before you pressed a button.

Coming back to why this topic is relevant to OneShot, this game manages to go beyond those boundaries by having characters discuss the player as well as the creator/OS as separate entities. This decision isn’t made without a purpose, and it’s ultimately what separates OneShot from others games by its meta-commentary. In short, if Undertale popularized the fourth-wall storytelling in the vein of Earthbound with a more self-critical look at the role of players in games and how much power they possess—and how terrifying that power is—then OneShot examines the masquerade of self-awareness not only about games but also of artificial intelligence.

Two Beta or Not to 2B?

Coding in OneShot is more than programmed responses in a game as the emphasis on how both organics and robotics NPCs have various levels of capabilities and self-awareness. The conflicts revolve around the main character, Niko, and the many other characters in the world; the player acting as a god-entity; the software itself as the narrator; and the files on your computer acting as the Author. Many games would conflate the idea of the creator being one with the software or recognizing the player’s avatar as the creator like in Tron (1982); however, in the case of OneShot, there is a schism of these roles and of their influence. The result is the characters are as much as “real” to the player as the player is to the world, to the files and to the software as the program recognizes your role when you launch the software, OneShot.

This idea will slowly unravel to its fullest as you notice the software, as well as the Author, are manipulating you by having you grow attachments, however small, to Niko and the world. From misunderstandings of purpose and of understanding the grand scheme, conflicts arise that further bring about the end of the fictional world. Some characters are enacting change alone or with another character that causes only further harm while others are inactive, relying on others to address the problems. Eventually, the game puts you into a choice of saving the needs of the many or the needs of the few, and the result will leave you wanting to replay the game to find some alternative.

Before the Solstice update, there was no alternative. Now, however, there is a True Ending that expands on these relationships between the game’s window, the files in your folder and the characters all wanting to express themselves as being more than simply codes on the screen. It’s only when all these elements come together to resolve the crisis is when everyone manages to find a solution and to find peace for themselves. As simple as the storytelling is on a fundamental level, however, it’s the exploration of these conflicts and the believability of its characters who question their purpose that truly steals the standing ovation.

Verdict: You Literally Only Get “ONE” Shot

As you might expect, this tagline is setting false expectations as no one would be happy to pay for a game you can only complete once. However, OneShot manages to get away with this half-truth to benefit the narrative with its “one-and-only-one” run.

Unlike Undertale that manipulated your emotions to demonize completionist attitudes and punish you replaying the game, OneShot goes for a more light-hearted approach of control. The game tests you not to come back by making the characters so real that, when everything is over, you let them go their own ways rather than undoing your actions. It’s why when the game is “finished” you’re left with a sunny screen that you can load up any time afterwards with no one there. An idyllic image of peace and the memories left with you by yourself is more rewarding than any guilt-tripping from Undertale to beg you not to play a great game again.

(Note: You can “true” reset the game like Undertale, so there is no “One” run.)