Explore Dunwall from a new point of view

Modiphius

Genre: Tabletop RPG

Developer: Modiphius

Publisher: Modiphius

Release date: July 06, 2020

In 2012 Arkane Studios released a little known stealth action game called Dishonored. It was billed as a spiritual successor to Thief: The Dark Project, though it really was its own thing. Two sequels followed, Dishonored 2 and Dishonored Death of the Outsider, before Arkane went on to make other things. This was not the end of the Dishonored franchise, and in 2020 Modiphious released a tabletop RPG based on Dishonored.

The Dishonored Roleplaying Game uses a simplified version of the 2D20 game engine, used in most games made by Modiphious. It’s a simple and narrative focused rule system that requires some work from the GM to run smoothly, but gives the players a lot of freedom over the direction the game will take.

The Setting

Dishonored is set during what can best be compared to an exaggerated Victorian-age Britain. Most of the known world is controlled by a large empire, which has colonized and conquered its way to where it is now. The world of Dishonored is made up of a series of islands, both large and small, many of which have different cultures and customs. Most prosperous of these is Gristol, a large island that houses the capital of the empire, Dunwall.

In the core rulebook the cities of Dunwall and Karnaca are given special attention. These two locations are given a lot of information, particularly in regards to locations and groups that were present in the videogames. These are huge cities, with Dunwall being based on London with its larger river running through it, large industrial districts and customs, where as Karnaca is more vaguely inspired by 19th century Spanish and Greek coastal cities.

The empire has in part made its mark on the world thanks to its technological superiority. With great machines and factories running on whale oil, a substance that can be used to generate enough power as to create gates of electricity and drive huge warships. The discovery of whale oil has allowed the empire to produce vast quantities of goods and even invent autonomous machines.

Sadly the wealth that the whale oil has brought in has not been evenly distributed. The rich live in grand palaces, never have to go hungry and are able to flaunt their wealth by constructing massive prestige projects. The poor on the other hand live in squalor, barely get enough food to stay alive and are forced to live in cramped conditions where diseases can run rampant.

Despite, or maybe because of, the technological progress magic has its place in the world. While rarely practiced openly witch covens exist in places that have more contact with nature. Certain people have also been given powers from another source, a mysterious being known as the “outsider”, who lends his powers to those he deem worthy.

Most of the major locations seen in the videogames, like the Flooded District, the Dust District and the Drapers Ward are given a page in the book, detailing what makes that area special and also gives some plot hooks. Many of the factions from the games, be it the Hatters, the Imperial Family or the Overseers are also given a page or two, including enough information to run campaigns centered around those groups, be it as a member of that group, or with them as antagonists. Sadly there’s not a whole lot of information about people and locations that were not in the games. There’s some, but you’ve got two major cities that are fleshed out, with locations and groups, but everything around those locations are given far less attention. If you’re a fan of the games and expect to see the setting expanded more you’re likely to be disappointed.

The descriptions of the two cities assume that you’ll be playing during the time of the videogames. That is if you’re playing in Dunwall you’re going to play during the rat plague of Dishonored 1, and if you play in Karnaca you’re going to play during the bloodfly infestation of Dishonored 2. You don’t have to do this, but if you’re not you need to tweak some things.

The Rules

The rules in Dishonored might seem a bit weird and ambiguous at first glance, and sadly the rulebook itself does a pretty poor job at actually selling you on its rules. In fact after reading the rulebook you might come off thinking that the rules seem terribly messy and hard to use. But the game runs a lot better than it reads and it does not take long for the quirks of the rules to start making sense.

A character has two sets of stats, called “skills” and “styles”. The Skills are Fight, Move, Study, Survive, Talk and Tinker, while the styles are Boldly, Carefully, Cleverly, Forcefully, Quietly and Swiftly. Whenever you make a skill roll you combine two of those that make sense for the situation. If for an example if the GM wants to see if you spot something moving in the corner of your eye “Study” and “Swiftly” would be combined, while if you try to bullrush someone “fight” and “forcefully” would make sense to mix. Then you roll 2 20-sided dice and any die that comes up lower than the sum of the skill and style counts as a success. This system is flexible, though it requires the GMs and players to be able to make fair judgment calls on what skills and styles are appropriate for any given situation. The included adventure gives a lot of examples of this, but the rules themselves could also have used a few more. For a normal difficulty challenge a single success is usually needed, but tougher ones might need more.

A character will also have a number of focuses, which are specific things that they are better at. Normally if you roll a 1 on one of the 2D20s that counts as two successes, but if you’re doing something you have a focus in you have a greater chance of getting two successes. Focuses have a number, and that’s the “crit range”. Let’s say that a character has Archery 4, then any roll of 4 or less would count as two successes.

What does set the rules used in Dishonored apart from many other RPGs are the so called “meta currencies” . Currencies that allows the players to more directly influence the world. These don’t make much logical sense, but are used to allow players to shine at opportune moments, or allows the GM to throw a wrench in the plans of the players without it seeming arbitrary. These really needs to be used within reason to work, which is great if the group is focused on telling good stories and roleplaying, but a group that wants more tactical play might find them disruptive.

There are three currencies, and they work somewhat similarly. The first one is momentum, and is a currency the players share. Any time a player rolls more successes than needed for a skill roll they might add another momentum. Momentum can then be spent to either add more dice to a skill roll, or to create a “truth”. A truth is a small description of something. Like say “the guard is asleep” would be a truth, “the window is open” is another truth that would be okay. “The house is suddenly collapsing for no reason and everyone dies” would not be allowed. Truths still need to make sense. See it as the players interjecting and adding their own piece to the story.

The second currency is “chaos”, which is similar to momentum, but for the GM. Any time the players kill someone, or do something that would create a lot of disorder, like say incite a riot, chaos gets added. The GM can use chaos to create truths of their own that mess with the players like “There’s a guard on the roof” despite the players having intel that would indicate that there would be none, or to add dice to a skill used against a player.

Finally there are Void points, which are individual to each character. A single void point can be used to reroll the dice from a failed skill roll, create a critical success, or create a truth through slightly more supernatural means. The GM still has the final say over any truths the players want to make, but the nature of void points means that they can be slightly more weird.

Combat follows the regular rules for the game. When making an attack fight + an appropriate style is rolled and if you roll enough successes you hit. Depending on the situation this might just be a regular “roll a certain number of successes” roll, or a contested roll, where the side that gets the most successes succeeds. If you hit you deal damage, and major NPCs as well as characters have health equal to their “survive” skill, while minor NPCs go down in one hit. As killing someone increases the chaos score a player might try to incapacitate an enemy instead, which adds one to the difficulty of the test, but otherwise combat is very straight forward. With one exception: Handling distances. Dishonored uses abstract distances, that is to say you don’t measure distances in meters (or feet) but instead someone might be “nearby” or “distant”. Making distances abstract is not a bad thing for a narrative focused RPG that’s more concerned with keeping the story going rather than worrying about exactly how far away someone is, but Dishonored lacks examples of roughly what “nearby” means. A few examples would have gone a long way in making it easier for a GM who’s new to the game run combat encounters.

Near the back of the book there are rules for a bunch of NPCs. Many of them generic, like guards, overseers and wolfhounds, but many of the major characters from the games are also here. If you want to put Corvo or Sokolov in your game then they have stats. There are enough different example NPCs here for it to be pretty easy to get an idea of what’s appropriate for when you make your own, when it comes to stats and abilities.

The Player Characters

With a simple rule system comes simple character creation. When making a character you simply select one of the included archetypes. There are 13 different archetypes in the book, and these range from scout to inventor to entrepreneur. They’re in other words pretty broad archetypes. Each archetype adds points to three skills, and then lets you pick two out of a list of three talents and improve those as well. Any skill or talent that you’ve not got anything in starts at four, and the maximum value they end up with at start is six (unless you use some optional rules for creating more powerful characters, more on that later). They also get four focuses that they can spend eleven points between. Each archetype has a couple of recommended focuses, but players are free to pick what they want, or even make up their own (with the GMs permission).

Each character also starts with a single talent, and every archetype has four different ones to pick from. For an example an explorer might reduce the difficulty of creating maps or giving directions by two, and a sharpshooter has the ability to spend a momentum to reduce the difficulty of a shot by one. Most characters also start with one contact, though some archetypes gives you more, as well as a few different pieces of starting equipment.

The above system creates characters that are better than the average person, but not exceptional. There’s rules for actually making heroic starting characters in the game. When you do that you pick an “outlook”, which works similarly to the archetypes. Every outlook gives a different set of skill and style bonuses, as well as another talent, picked from a list of three that are unique to each outlook.

Character advancement is also simple. Characters gain experience points which they can then spend on improving their character. 10 xp can be spent on improving one skill or style, or gaining one new talent from your archetype, and focuses gain be gained at the price of 5xp per focus point. You can also gain a talent that’s not from your archetype for 15. Experience is gained the usual way, the GM hands them out after sessions depending on how far they progressed, but the book also recommends giving experience to characters who suffered adversity. Say they got injured or they suffer complications from failed skill rolls.

Characters can also get bone charms. These are magical artifacts carved out of whale bone which give some kind of passive bonus. Bone charms can also have a negative effect if they’re corrupted (which represents that something went wrong when they were made). For an example a high quality bone charm might give you an extra D20 whenever you do something “forcefully” while a normal bone charm might make your footsteps make less noise. Negative effects can include making the character look sickly or only work during night.

Finally a character that somehow bears the outsider’s mark (something the GM needs to allow to begin with) can learn magical powers. Some of these powers require an action and has an immediate effect, like the ability to summon a swarm of vermin to devour your enemies or the ability to see nearby creatures, even through walls. Some are passive and give bonuses like gaining extra successes when trying to do something that requires agility or the ability to make anyone you kill instantly turn to ash.

The Included Adventure

There’s an adventure included at the back of the book that takes place before the games normal timeline. All the players play as a group of people who tried to throw off the yoke of the empire and failed, so now they’re on their way to prison. The adventure is alright as an adventure, and has some nice scenes, but can at times be slightly too railroaded with only one solution being really all that viable. It does a good job at introducing the setting and its themes though.

The main strength of the adventure is that it gives clear examples of when and how certain rules should be applied. With a ruleset as open-ended as the one in Dishonored it’s nice to get a few concrete examples of where the lines go, so it’s worth reading through the adventure for any GM who wants to run Dishonored, even if they don’t plan to actually run it.

Art, Layout & Quality

Almost all the art in the Dishonored RPG is taken from the videogames, be it from promotional art, loading screens or paintings inside the games. The art is really good, helped by excellent print quality, but it does mean that the RPG feels like it lives in the shadow of the games that they’re based on. A few pieces of art that shows more of everyday life in parts that we’ve never seen before would have been nice.

There’s a short comic, split into two parts, at the start of the book that is meant to help introduce some of the games concepts. It’s fine, but the artwork in it is not outstanding. It’s also not quite as good at teaching the games concepts as the authors probably hoped for.

The layout of the book is pretty typical for a modern RPG. Most things are in logical places and grouped together well. Finding what you need in the book is not very hard. It’s a good thing that the game is as rules light as it is though, because several page references point to the wrong page. This is a common enough issue for it to be noticeable and irksome.

As for the physical book itself, it feels sturdy, like it can handle being used without you having to worry about pages falling out. Only time will tell if it is as sturdy as it feels, but it would be surprising if the book were to start falling apart any time soon. The paper also feels high quality and like it would take a lot for it to rip. Overall the quality of the book is up there with the very best of them.

Closing Thoughts

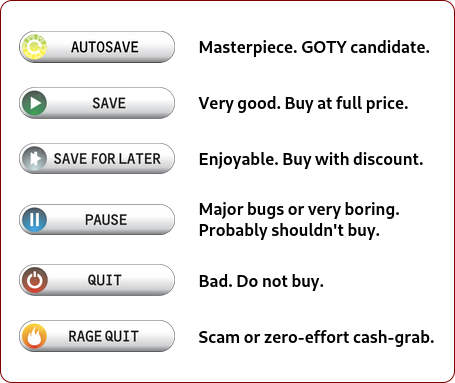

“Reads poorly but plays well” is how I would sum up Dishonored. When I read the rules for the game I felt like it would be a very messy game to run, with a lot of things being left up to the GM to decide during play, but when put in action Dishonored felt really good to play. It was not too hard to get a feel for the rules when they were put in action, and many of the games odd quirks all of the sudden started making sense. Dishonored is a game that’s both fun to GM and to play, and the rules are fast and easy to teach. People who are looking for a deep tactical experience should look elsewhere, but anyone who enjoys narrative focused RPGs should give this one a look, particularly those who like the Dishonored setting.

I do have one major criticism of the game though, and that’s how much it feels like it lives in the shadows of the videogames that it’s based on. The setting as presented here never really strays far from what’s already been established in the videogames, and while it’s nice to get a refresher on those areas, and read a bit about how everything fits together it would also have been good if there were more information about the things that we don’t see in the videogames. Even if the authors of this RPG just wanted to focus on Dunwall and Karnaca those cities are supposed to be pretty big, with a lot of interesting people and places. Hopefully there will be some expansions coming out that will flesh out the rest of the world a bit more, because it is an interesting setting. Still there’s enough in here for Dishonored to be a solid RPG well suited for both long campaigns and quick one-shots.