Crawling through hexagons in a ravaged land

Free League

Genre: Tabletop RPG

Developer: Free League Publishing

Publisher: Free League Publishing

Release date: 6 Dec, 2018

Hexcrawling has been around in RPGs since the early days, though its popularity waned by the time the 90’s rolled around. While hexcrawling never died out, it felt like Free League helped re-popularize this style of gameplay with their first international success, Mutant: Year Zero (even if that one did use squares rather than hexagons). Forbidden Lands shares a lot of DNA with Mutant: Year Zero, but is even more focused on the sandbox experience.

Forbidden Lands is a fantasy RPG set in a ravaged land, where travel has for a long time been impossible to all but a few individuals. Though now the land has one more become accessible and people are starting to explore it. Thanks to this large parts of the land is unknown to most, even though most of it is populated.

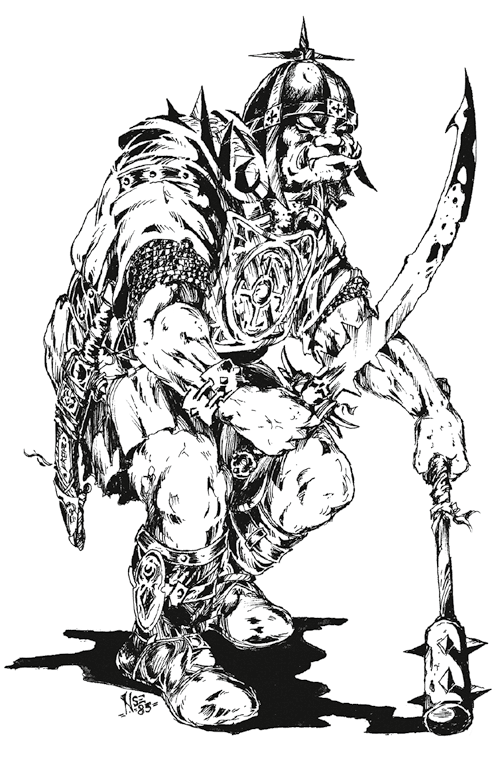

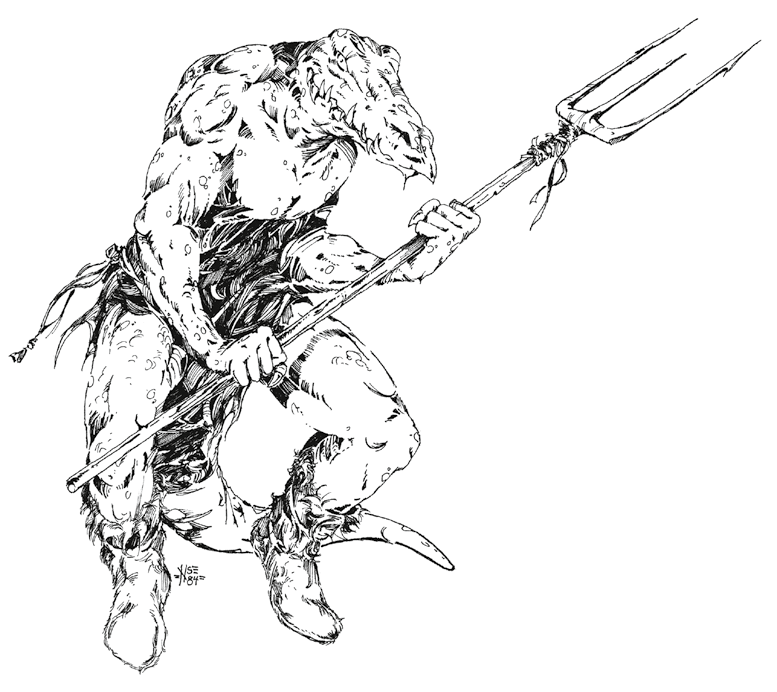

Though not quite an OSR game, Forbidden Lands is an attempt at creating a game that captures the feel of RPGs from the 80’s, even going so far as to let an artist who helped illustrate some of the most prominent Swedish RPGs of that time do most of the art. It’s a classic fantasy RPG where the players play as adventurers (though not necessarily heroes) who explore a dangerous fantasy world. The game does use a modified Year Zero engine though, which is a modern ruleset used in most games by Free League.

This review is based on the Swedish edition of the game, and a few terms might end up being mistranslated here, though the game should be more or less the same no matter what version you use.

The Setting

The Ravenlands has been inaccessible to travelers for nearly 200 years, as the blood mist covered the land. Something in the mist hunted those who travelled too far from their homes, and only a few had found means to safely traverse it, chiefly among those the Rust Brothers, a fanatical, and dangerous, cult of humans who worship the gods Rust and Heme, and thanks to their ability to traverse the blood mist they’ve been able to gain knowledge and power that’s been out of reach for most people.

But the blood mist is now nearly gone, only small pockets of it remain, and people can once more travel through the Ravenlands. Villages separated from each other during the time of the blood mist can finally contact each other, and people are finally no longer just bound to their home area. But the Ravenlands is by no means a safe place to travel through. Not only are raiders and bandits taking this opportunity to gather wealth and power, but the rust brothers are always on the hunt for “heretics” and terrible creatures are lurking in the forests, swamps, caves and ruins that litter the land. Some among the elves and dwarves also blame the humans for what happened with the blood mist, and they would not be entirely incorrect in doing so.

The humans are not native to the Ravenlands, instead they migrated in from outside. The first group of humans came in peace, seeking a safe place to live, away from conflicts and persecution, though soon other groups of humans also entered the Ravenlands, humans who’s intentions were not as pure. Several wars followed, culminating in the wizard Zygofer opening the gates to the daemon realms. Daemons flooded out and ravaged the lands, killing anything that came in their way.

Both the elves and the dwarves had, according to their legends, been given orcs as servants and protectors, and tried to hold back the daemons using the orcs as a shield. But when the orcs were unable to hold against the daemons the elves and dwarves fled, leaving their former servants behind to fend for themselves. Among the orcs this was seen as a great betrayal, and most orcs despise their former masters for it.

Many of the elves who are now alive remember these events, and some blame all humans for what happened. The dwarves, while not as long lived as the elves, are also not necessarily fond of humans because they allowed this to happen. Some hardliners within these folks wants to see all humans killed or driven out, while others are more interested in rebuilding the land and making it safe for travelers once more.

Orcs, elves, humans and dwarves are not the only races, or kin, populating the Ravenlands, even if they are the major powers of the land. Wolfkin are seemingly relative newcomers, some believe that they’re an effect of the daemon flood fusing man and wolf together, but wherever they’re from they’re here to stay. Wolfkin prefer to live in forests with their packs, where they hunt together, though a few have ventured out into more populated lands and found work there. Most elves despise wolfkin, as they seem them as unnatural. Halflings on the other hand are more well liked, and are often jovial and friendly, though it’s uncommon for halflings to invite a stranger into their home and they’re often very secretive. Then there’s the goblins, who for some reason seem to be drawn to halfling lands, and are often found in the forests near halfling dwellings. Goblins are rarely as jovial and friendly as halflings, and most halflings don’t want them there. There are a few other minor kin, like ogres, lizardmen and so on, though none are as integral to the game world as the earlier mentioned ones.

The world of Forbidden lands is not quite dark fantasy, in the way of say The Witcher, Warhammer or even Symbaroum, but it’s also not the heroic fantasy akin to what you get in Faerûn (Forgotten Realms/D&D), it lands somewhere in-between, though leaning more towards the darker side. It’s probably best compared to something like the setting in the Conan books (and not the movies), with a dash of Earthdawn (an old fantasy RPG by FASA that also had a land that had been inhospitable for a long time, and just recently opened up for travel). It is a setting with a lot of conflicts though, where all the kin have reason to hate each other.

The setting of Forbidden Lands does at time feel like it was written to be a game world first and a living breathing world second. Having a lethal mist cover most of the lands is a pretty convenient way to make sure that that the player characters know very little about the world around them, and it also gives an excuse for there to be ruins and caves populated by monsters and other nasty things littering the land. That’s not to say that the Ravenlands is not a good fantasy setting, and some of the lore found in the Game Master’s section is quite interested, but the world does not feel as convincing as that of say Symbaroum, though it does make more sense than the classic kitchen sink fantasy settings that you see in some other RPGs, like Faerûn (D&D) or Golarion (Pathfinder).

The Rules

Forbidden Lands runs, much like most other games by Free League, a modified version of the Year Zero engine. The Year Zero engine is a dice pool system, where, when you’re trying to perform a task that requires a skill roll, you roll a number of (mostly) six-sided dice equal to your attribute, related skill and any bonuses that comes from an item you’re using, and any die that comes up a six is a success. You can at times get dice that are not six-sided, and then any roll over a six is a success, with really good rolls giving multiple successes. It’s important to keep the dice from the three “sources” separate (using different coloured dice). What sets the Year Zero engine apart from most other dice pool games is the ability to “push” rolls. If a roll fails, or even if it succeeds, but you’re not happy with the number of successes you rolled you can chose to re-roll any dice that did not come up a six or a one, though at the risk of taking damage. The rules for pushing a roll is more similar to those of Mutant: Year Zero than Alien, in that any die that comes up as a one will cause some negative effect.

As for the nature of the negative effect, that will vary depending on the source of the die. Any skill dice are fine, they don’t hurt you, but any attribute die that comes up as a 1 will hurt your character, and you’ll take a point of damage to the related attribute, though it’s by pushing yourself to your limits that you also earn the power to use your most powerful talents and magic. Any dice that comes up as a 1 from an item will instead damage the item, which will lower its effectiveness until it’s repaired.

As this is a fantasy game about adventurers traversing a dangerous land combat is more or less inevitable. Not all combat has to be about bashing in the skull of someone with a sharp metal stick though, sometimes combat is done with sharp words. The rules for combat follows the rules for doing skill checks, including the ability to push your roll, though there are a few additions to it. For one combat is done in rounds, using an initiative system. At the start of combat every player and creature who’s in some way involved (willingly or not) draws a card with a number between 1-10 listed on it (or as we did for this review, rolls a standard D10 and just re-roll in case two people get the same result), and lowest goes first. There are talents and monster abilities that can complicate the initiative order slightly, but overall it’s a straight forward and simple system that does not bog the game down in initiative minutia.

When it’s your turn to act you can do two actions, one short and one long, or two short actions. Long actions include most offensive abilities, like attacking or using magic, while short actions involve things like aiming, defensive actions and moving. It’s a system that should be familiar to most people who have been playing RPGs, as the long/short action distinction is pretty common (and for good reason, with a few exceptions, most RPGs that deviate from this formula tend to either overcomplicate things, or become very static). Attacking is the most basic action, and you do a basic skill roll to hit, modified by the weapon you’re using, and if you hit you deal damage equal to the damage characteristic of the weapon plus one per extra success beyond the first, and then minus any damage mitigated by the armour. Armour rolls work like a skill roll, but it just uses the armour value, and no attributes and skills, and any six removes one point of damage. As a fast action the opponent can also try to parry or dodge.

Damage is usually dealt towards strength when doing physical combat, though it does not have to be the case with all types of attacks. Every attribute can be hit in some way, and if any attribute suffers damage equal to their maximum value a character is considered broken. If the attributes that were hit were either strength or intelligence and its value reaches zero the character will suffer critical damage, which is often quite bad. When a character takes critical damage you roll on a table at the end of the book to see what kind of damage they’ve suffered, with some results being potentially deadly, or leaving lasting injuries.

Combat uses zones, rather than exact distances, to determine how far away someone is. You can move one zone per short action that you spend on movement, and zones vary in size to represent this, a zone on open ground for an example would be larger than a zone in swampy ground where your movement is hindered. In buildings or dungeons a room is usually a zone. Zones are a good way of handling distances when you’re not using a grid of some kind, as keeping track of exact distances can be annoying when everything is done in your head or on a quickly scribbled map, but a few example zones could have been handy just to give a general idea of how large a zone should be. In confined spaces zones are easy enough to work with, but on open ground it leaves a lot of room for interpretation.

Magic in Forbidden Lands is both dangerous and tough to use, but can, if used right, be really powerful. In order to cast any spell a character needs access to the kind of power that they get from pushing themselves to the limits (through pushing rolls). You can spend more points to increase the odds of the spell becoming more powerful, but every point you spend also increase the risk of a missfire, and missfires are bad news as the effects can be quite punishing.

One issue with the magic system is that it can look so dangerous and inaccessible that players are dissuaded from even trying to play as a character who’s capable of casting spells. At the same time magic is not as necessary as in some other tabletop RPGs (like say D&D), so there’s less of a reason for players to pick a caster in Forbidden lands. And it’s true, magic has the potential to be very dangerous to the user, and a magically capable character won’t be able to just cast spells whenever they want, but a well placed spell can still be extremely useful.

Monsters sometimes break the typical rules, and follow their own slightly different ruleset. Not all monsters have all attributes, and if a monster is missing one it can’t be damaged that way. They also have access to monster attacks, which are random attacks that often have some additional effect. A hydra for an example can try to terrify those around it with a blood curdling scream, use its tail as a whip or spit acid. Not all monsters have special monsters rules, some are similar enough to the playable kin that they follow the same rules as them, but the very non-human ones are distinctly different.

The Characters

Character creation is a pretty simple process, and should seem familiar to anyone who’s played any other Year Zero engine game, though as this is a fantasy game you’ve also got a kin to choose, beyond your profession/class.

The first thing you’ll do when making a new character is to pick a kin. Each kin comes with its own unique talent and also an attribute that they can raise above the normal maximum. The kin are humans, elves, half elves, dwarfs, wolfkin, orcs, halflings and goblins, though the book recommend that newer players stay away from orcs, as these are hated pretty much everywhere, and are tougher to play (not that there’s not a lot of conflicts between all the kin as is, but orcs are hated even more than most).

After picking a kin you’ll get to pick a class, or a profession as it’s called here. Each profession has an attribute that they can raise above the normal maximum, which is cumulative with the kin attribute (so if both your profession and kin allow you to raise strength to 1 above normal maximum you can now raise it to two above the normal maximum), as well as three unique talents, and a few skills that you can raise to a higher value than normal at character creation. The talents is what sets the professions apart from each other, and makes a minstrel work differently to a hunter. Two of the professions, druids and sorcerers, are capable of learning magic, while the rest have to stick to mundane means of getting by.

Once you have a kin and a profession it’s time to start allocating points. Depending on the characters age you get a varying amount of skill and attribute points, with younger characters being less skilled but having more attributes. No attribute can be raised to a value above 4, except for your kin and profession attributes, which can be one higher. There are just four attributes, strength, agility, wits and empathy. There are also 16 skills, each one linked to a corresponding attribute. Normal skills can only be raised to 1 at character creation, but any skills listed on your profession can be raised to three. Finally you get a number of talents, one for your kin, one for your profession (out of three), and a number of generic talents depending on the age of your character.

Talents are varied and really help define what a character is especially good at. All talents, apart from the kin one, have three levels, with the later levels either being stronger than earlier ones, or adding more options. Profession and kin talents, much like magic, requires you to exert yourself in order to use, and thus you can’t just use them whenever you want to, but they’re on the other hand often quite impactful, while generic talents are passive and not as strong. A thief can for an example use one of their unique talents to almost perfectly blend in (if it’s reasonable) and look like someone else, while a hunter can fire an arrow with such precession that it bypasses any armour. This is a lot more impressive than the generic ones which include things like you get an extra die when attacking with a blunt weapon, or you can harvest the skin of animals and get valuable furs and leather, though the generic talents don’t require any resources to use.

Characters can of course also gain more power over time. Experience points are used to raise skills and get new talents. The book has a list of things it suggests gives experience points at the end of a session, like did a character defeat a monster, or did its personal secrets come into play during the game. Or the GM can just choose to give a flat number of experience points to the group, it’s really up to each group to decide what they think is most fun and fair.

There is an alternative way of making a character included in a separate pamphlet in the box, and that is by using a life path system, where your character will have had a number of events through their life that will define them and decide what their starting skills and attributes will be. The events can either be chosen or randomized, and has the advantage of creating well rounded characters and it also gives you a starting point for your backstory, though on the flipside you have less control over how your character will turn out. Overall it’s a pretty well implemented version of the lifepath system, and it also works great for players who are unsure of how to build their characters or don’t know exactly what to play.

Exploration and the Home Base

Free League loves to add home bases to their games, that can be expanded over the course of a campaign. Most of their games have something akin to this, be it the ark in Mutant, your spaceship in Alien or your base of operations in Vaesen. Forbidden Lands puts a pretty heavy emphasis on the home base, called a stronghold, and it’s assumed that the players will use this place to store their belongings and rest between adventures. It’s entirely possible for the players to own more than one stronghold, and in long campaigns it’s not unreasonable for them to have several scattered through the land.

The stronghold starts out simple, with only some basic facilities (depending on what the GM finds appropriate), but it can be expanded greatly from there, by building new rooms and buildings, or hiring people who can work there and take care of the place when the player characters are out adventuring. Over time the stronghold can evolve into an entirely community, with blacksmiths, bakers, farmers and shepherds keeping the stronghold running and providing food and services to the players, while soldiers keep watch and fend off any invaders, though to get that far you need both money and materials, something you’ll get from adventuring and exploring, as well as trading with the locals.

The stronghold can also be attacked, and besieged, by bandits and monsters. The more famous the player characters are, the more likely their fort is to attract unwanted outside attention, so skimping on defenses can be both dangerous and costly.

Exploration is a key element to Forbidden lands, and there are rules for exploring new hexagons on the world map, as well as event tables and survival rules. Getting food and water is important when out exploring and traversing through unexplored terrain can be dangerous. Having someone who can hunt, and someone with wilderness experience is useful, as is knowing how to safely make a camp that’s not drawing too much attention from any bandits or wandering monsters.

The exploration rules makes it really easy to run Forbidden Lands with next to no preparation, as there are tables for randomizing new locations, depending on what kind of terrain they players are going through. Villages, dungeons and fortified locations can all easily be created with a few dice rolls and the random events can create for entire adventures on their own. The game is really at its best when you mix in both a few pre-set important locations with the randomly generated ones though. And there are three pre-set locations included in the Game Master’s guide that can be thrown in where the GM thinks it’s appropriate. These do, to some extent, tie in with the Raven’s Purge campaign though, so if you intend to run that it might be worth holding off on using those locations.

Layout, Art and Quality

Forbidden Lands is sold as a boxed game. The box contains two roughly evenly sized books, one that contains most of the rules and information that the players need, and one for the GM that contains most of the lore, monster information and so on. On top of that there’s also a smaller stapled pamphlet with some additional material, a large double-sided hexagon map of the Ravenlands and a sticker sheet that can be used to mark important locations on the map.

Free League are well known for their quality books, and Forbidden Lands is no exception, though the retro-approach to these books make them look a bit less lavish than what you might expect, if you’ve only played modern RPGs. The books are sturdy hard cover books and have a faux leather cover, with the text and images embossed in gold. The books are really good looking. In the books themselves everything is black & white, many of the graphical elements, be it the flourishes at the top and bottom of the pages and the images look like they might belong in an RPG from the mid 80’s. Which is understandable, as many of the images in the books are from an RPG from the mid 80’s, namely the classic Swedish RPG Drakar & Demoner. There are a few new images mixed in, done by the same artist who did the old ones.

Luckily not everything about the books feels like something from the 80’s. The binding on the books is really good, and feels sturdy, which is far better than the often stapled or glued books you would get back then. The overall layout of the books is also good, and it’s easy to find what most relevant information without having to flip around too much in the book.

One area where the physical version suffers a bit are with the maps of the three locations that are included in the GM’s guide. These take up two pages, and sadly the maps can be somewhat hard to read where the pages connect to the spine. as this is the center of the map it’s also where a lot of the important stuff are located. This is not a problem with the PDF version though, for obvious reasons.

Closing Thoughts

I really enjoyed running Mutant: Year Zero, and found the exploration and base development in that to be both interesting and really fun. Forbidden Lands does what Mutant: Year Zero did, but in large it does it better. The settings are of course vastly different, but Forbidden Lands makes it really easy to run a sandbox campaign about exploring a ruined world, and it would be pretty easy to port the game over to another setting, as the rules and setting are not heavily intertwined. You can of course run a more traditional linear campaign in Forbidden Lands if you want to, and it would work just fine, but it’s the hex crawling, and how well it’s implemented, that really sets this game apart from other fantasy RPGs.

There is more to the setting than mentioned above in the review, but a lot of it is in the GM’s guide for a good reason. The setting, from a player’s perspective, might be one of the main weaknesses of the game though. There’s a lot here, but if you just go by what’s in the player’s book, the setting might seem like it’s just another fantasy setting, that just so happened to have had an evil mist covering it for a long time. I would recommend that any GM who intends to run the game tell their players a bit more about the setting and its factions and gods than the player’s book does (maybe tailor some of the information depending on what kin the players choose to play).

Forbidden Lands is a surprisingly easy game to run as a GM. The rules are not too complex, although it is one of the more complex Year Zero engine games, and because of its setting it is pretty easy to slot in ideas, locations and NPCs that you’ve shamelessly borrowed from other sources, as long as they’re not major cities or other densely populated areas. Forbidden lands is not an RPG that tries to do everything, it does not do court intrigues and that sort of stuff particularly well, instead it’s a game that’s focused on, and excels at, exploration and discovering new locations, as well as dealing with whatever happens to be there. It also does wilderness survival really well, with rules that gives a good representation of what it means to move through an unexplored and untamed wilderness, where food and water is not necessarily easy to come by, without getting bogged down in details.