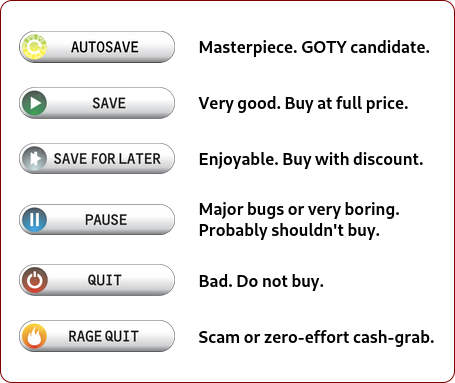

Like gaining check by putting your queen where it can be taken by a pawn, 5D Chess is a great idea that didn’t quite think things through.

Type: Single-player, Multiplayer

Genre: Strategy

Developer: Conor Petersen,

Thunkspace, LLC

Publisher: Thunkspace, LLC

Release date: 22 July, 2020

Intro

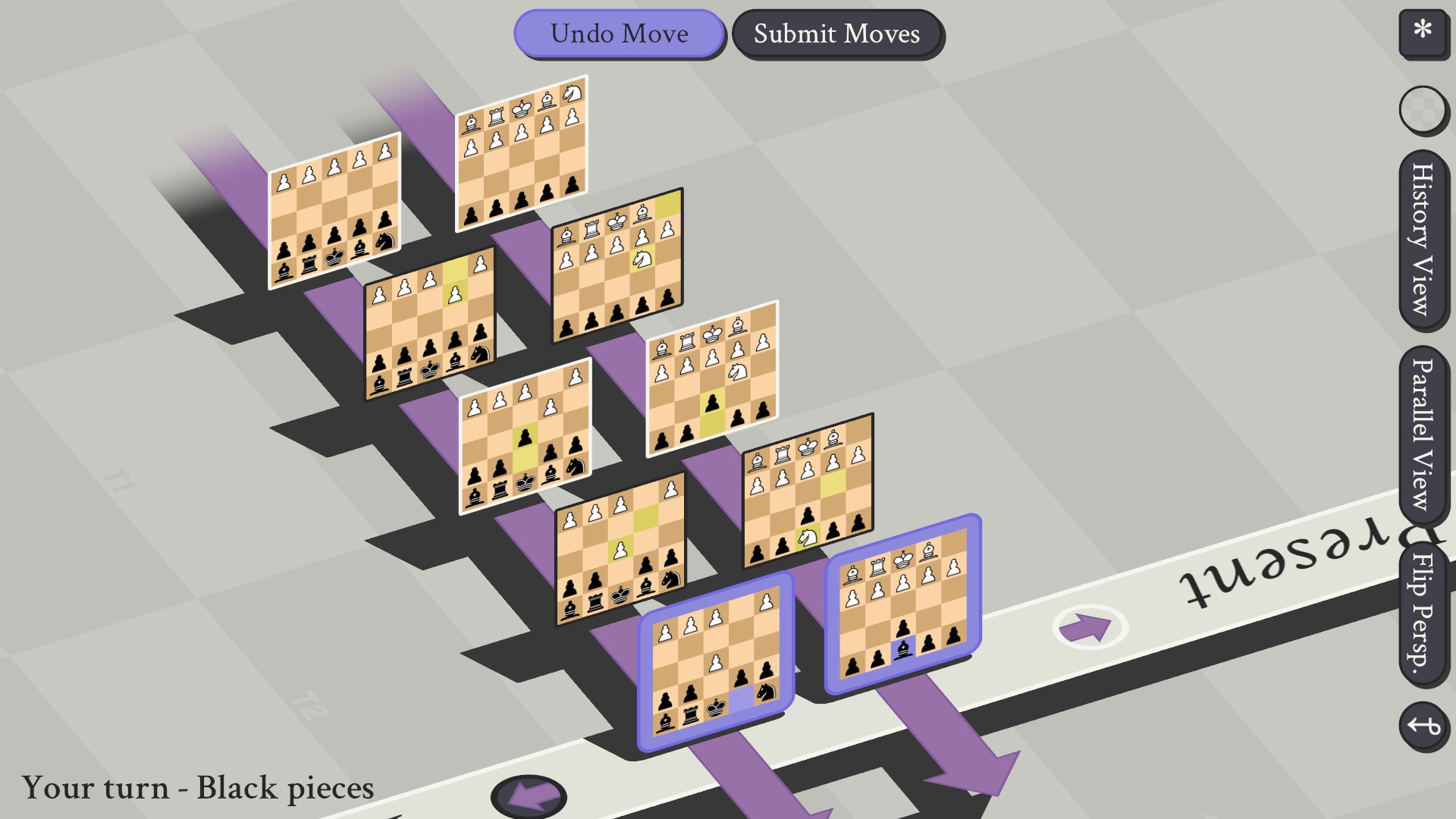

5D Chess With Multiverse Time Travel, or just 5D Chess from now on, because I’m not typing that full name out every time, is one of a multitude of games that tries to “innovate” upon the iconic classic game synonymous with strategy. Few of the many variants of Chess have ever stood the test of time, partly because simply holding a copyright on something like “Battle Chess” means that anyone trying to actually release a more modern version of something similar will just get sued and have their game blocked from sale anywhere the original game was available. This means that you need to endlessly reinvent the wheel as each new game tries to innovate on classic Chess, while each previous innovation on Chess is forgotten.

5D Chess tries to stand out from the crowd by latching onto the idea of “4D Chess” as a meme and trying to actually take the concept seriously, and see how the game actually plays out. Ironically, the result is one that often makes it seem like the developer didn’t plan the game out much further ahead than just setting the rules up, and just sitting back and seeing what would happen from there.

One person on Steam commented that they love the concept, but that they felt like they wanted to just take this concept, and make their own, better version of it, with a computer opponent that doesn’t blatantly self-destruct if the player simply lets it. Normally, this would be blowhard talk, but after reading that and looking at the game, it really does feel like it wouldn’t be all that difficult to replicate. The graphics are mostly open-source, the sound is totally open-source, the base mechanics are standing on the shoulders of giants (I can Google up video tutorials on how to program Chess in various programming languages readily), and from there, it’s mostly just programming the specific mechanics of the time-travel, and adding in the variant modes or puzzles. (And as I’ll cover later, most of the variant modes don’t feel like all that much time was spent ensuring they were well-balanced, and seem to be mostly throwing setups against the wall and changing them when players point out they’re broken…)

If nothing else, if you go through the trouble of learning this game, then the next time you hear someone insist that a blatantly stupid thing actually wasn’t stupid, but a brilliant 4D chess move, you can tell them that actually, you play 5D chess, and that was still a stupid move, and also, you just slapped them in the face through the past as they were saying it for suggesting something so dumb.

On Strategy

Allow me to digress to the basics to help set up a thesis going forward, and start with the nature of strategic thinking/strategic planning. Doing a quick Google, that Professor Collis of Harvard Business School in Thinking Strategically writes that, “strategic thinking is about analyzing opportunities and problems from a broad perspective and understanding the potential impact your actions might have on others.”

Or, for the purpose of my argument here, strategic planning is your ability to foresee the consequences of your actions several moves in advance.

Now, plenty of games have strategy in them, or at least, will punish you if you don’t engage in strategic planning. It’s absolutely strategic planning in Dark Souls to avoid attacking with button mashing because you know the consequence is that you’ll be interrupted or blocked and slain in a counterattack, and to instead dodge-roll behind the enemy as it winds up a swing to backstab them, instead.

For a “strategy game”, however, you are generally prevented from achieving goals in a small number of moves and your opponent can interrupt your plans easily. You can generally hold that a game is “more strategic” the more forethought it requires you put into every move you make.

Chess is a “solved game”. This means that it is hypothetically possible to run through every possible combination of moves any two players could possibly make in a game of Chess, and give a strict, specific formula of moves that a player of either color could make to either win any game, or else at least get a stalemate. The only problem is that even the fastest computers we have ever built will take until the Sun goes red giant and devours the Earth to actually compute every possible game. This is because the lower bound of the possible number of games that can be played is 10 to the 120th power.

Tic-Tac-Toe is also a solved game, but unlike Chess, Tic-Tac-Toe is simple enough that anyone who has played the game even a few dozen times will start to realize that there are very few actual moves to make. The permutations of possible moves (especially when excluding symmetric moves – by which I mean an X, O, X on the top row with the rest blank, and a X, O, X on the bottom row with the rest blank are effectively the same playstate) are so few that it’s possible for even people who aren’t exceptionally inclined to strategic planning can start to realize that there is a single perfect strategy, and move towards playing it every time. This leads to that famous line of Wargames, where “the only way to win is not to play,” as any opponent who understands the strategy will be able to force a stalemate.

Similarly, in memes, checkers is a solved game that is simpler than chess, but still advanced enough that it takes a pretty advanced computer to actually ram through every permutation of plays. That said, I’ve played RPGs with mini-games of checkers where the AI is extraordinarily difficult, simply because the game is simple enough that the computer can easily run every permutation of moves both you and it could take five moves in advance without significantly lagging your PS2 when it decides.

So… Why am I harping on what strategy is? Well, in normal Chess, a good player can see two or three moves in advance, accurately predicting a range of possible moves they will make most of the time (especially if they can put the opponent in check or otherwise restrain their opponent’s moves). Chess Grandmasters claim to see as many as fifteen moves ahead, although this is along a narrow line of possibilities, discounting possible moves the opponent might make because they are considered sub-optimal based upon a heuristic guess, and not followed through upon. In practice, even Grandmasters will “only” be seeing five or fewer moves ahead most of the time at most points in the game simply because at “open” portions of the game with many more permutations of moves than the early game (where most pieces cannot move) or late game (where few pieces are left, and therefore it is easier to see the effect of every possible move). (I should also note that the game Go has simpler moves – you can simply place stones on the board – and therefore fewer permutations of relevant moves available per turn, and therefore masters of Go will be able to plan even more moves into the future.) Beyond this, a master isn’t relying upon actually planning each move many moves out in advance, they are relying upon heuristics. That is, they are relying upon knowing that certain positions are more favorable or that taking a piece of the opponent’s and not losing one of yours in return is favorable to your long-term goals.

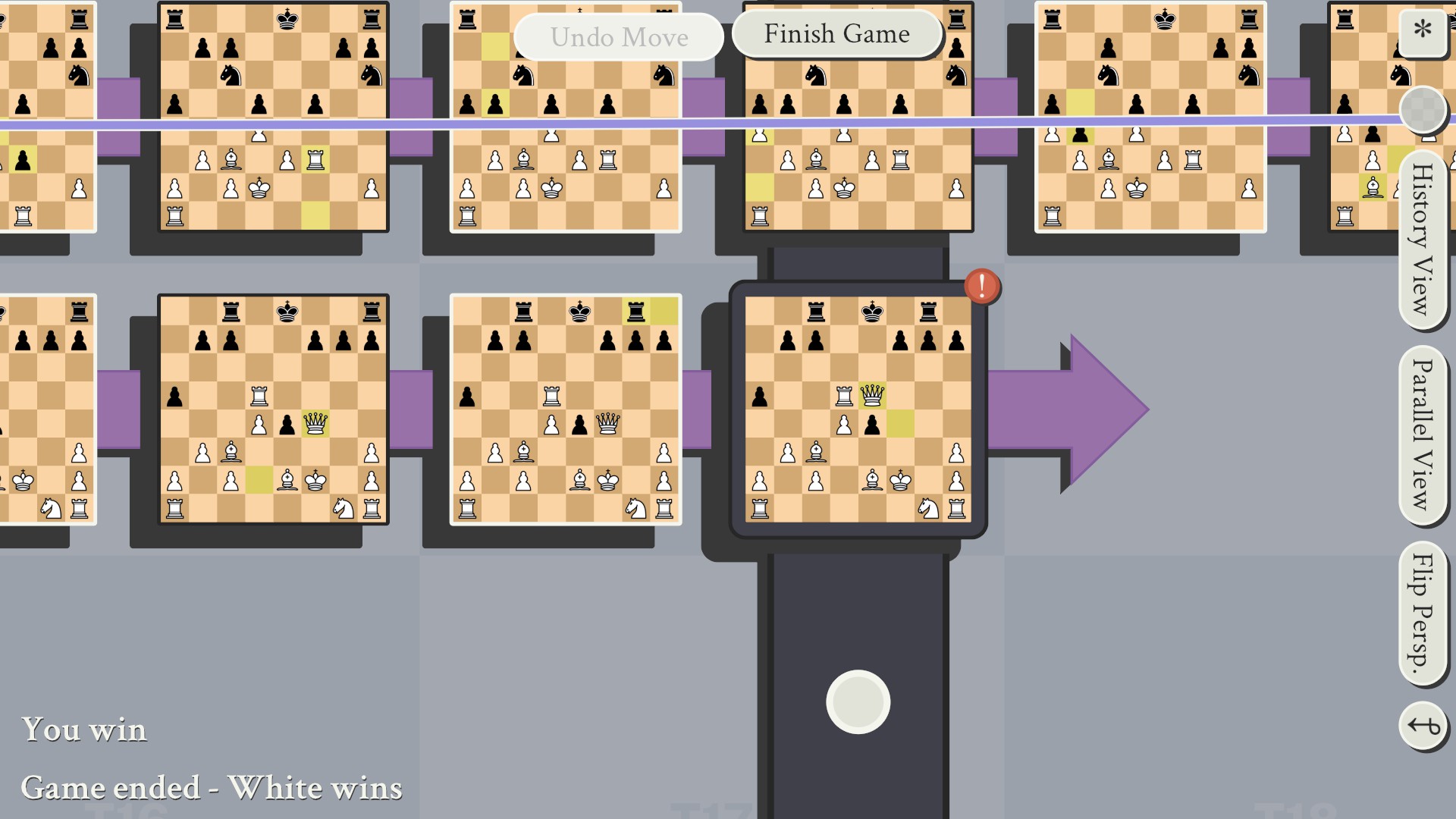

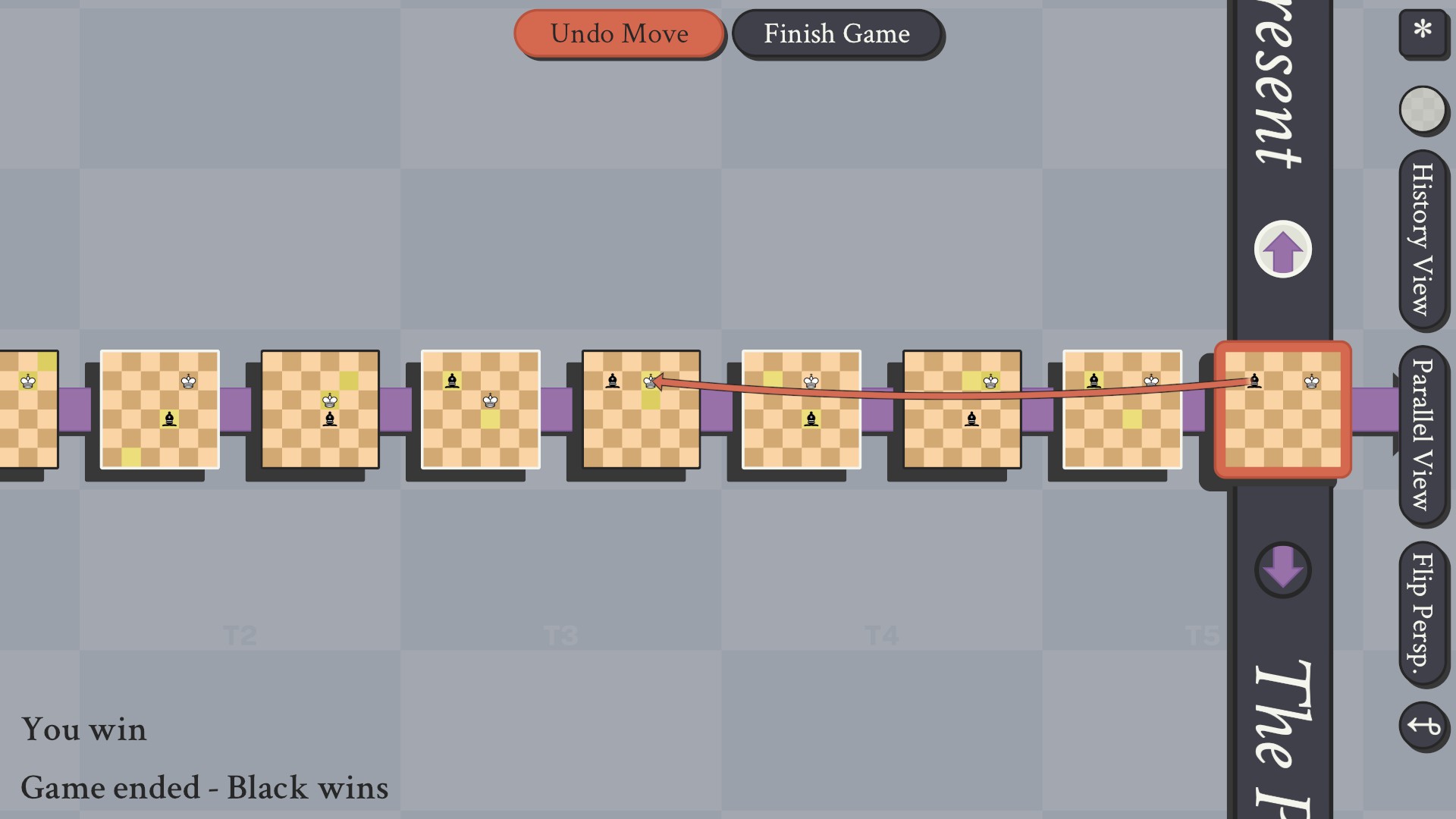

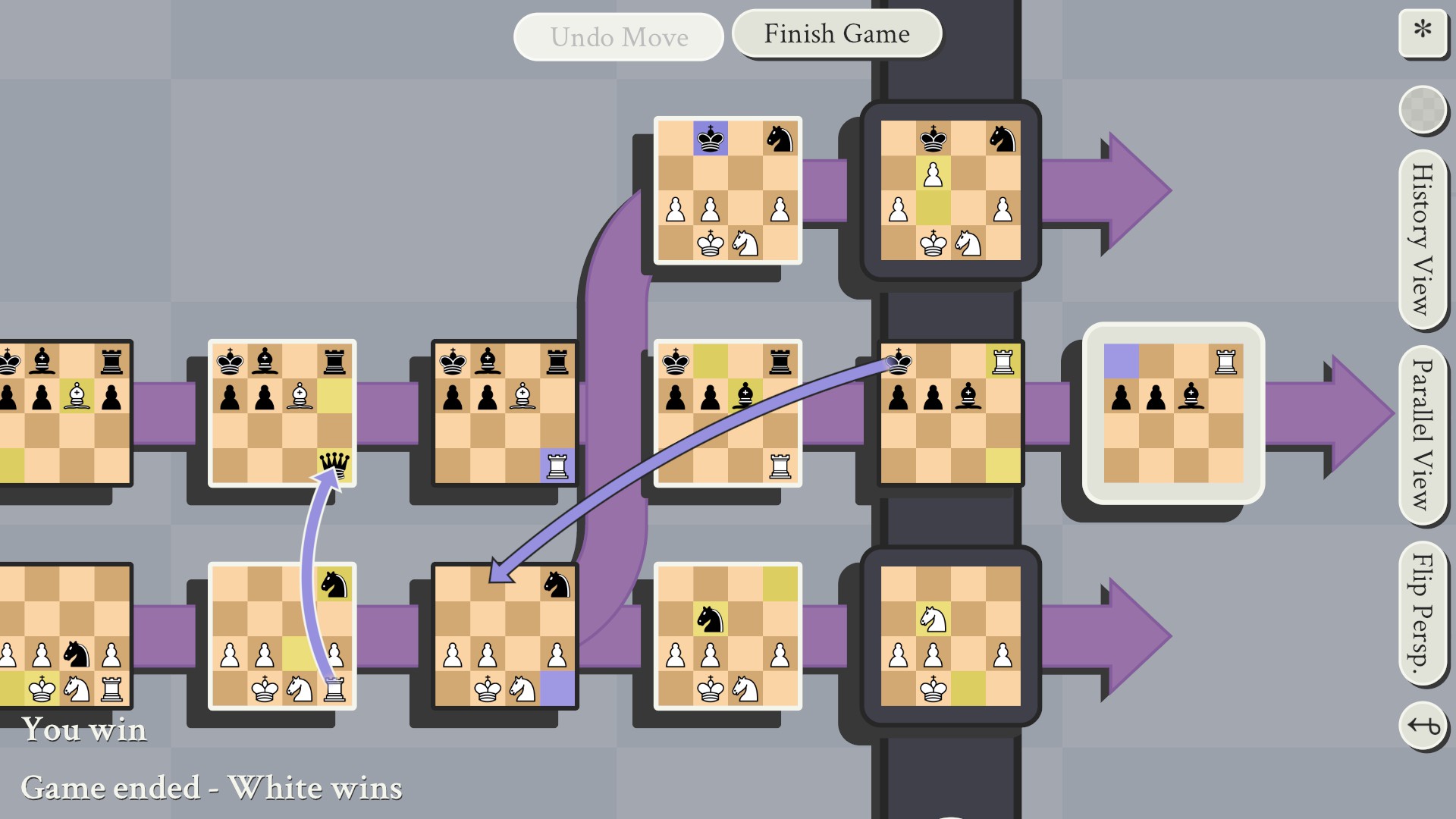

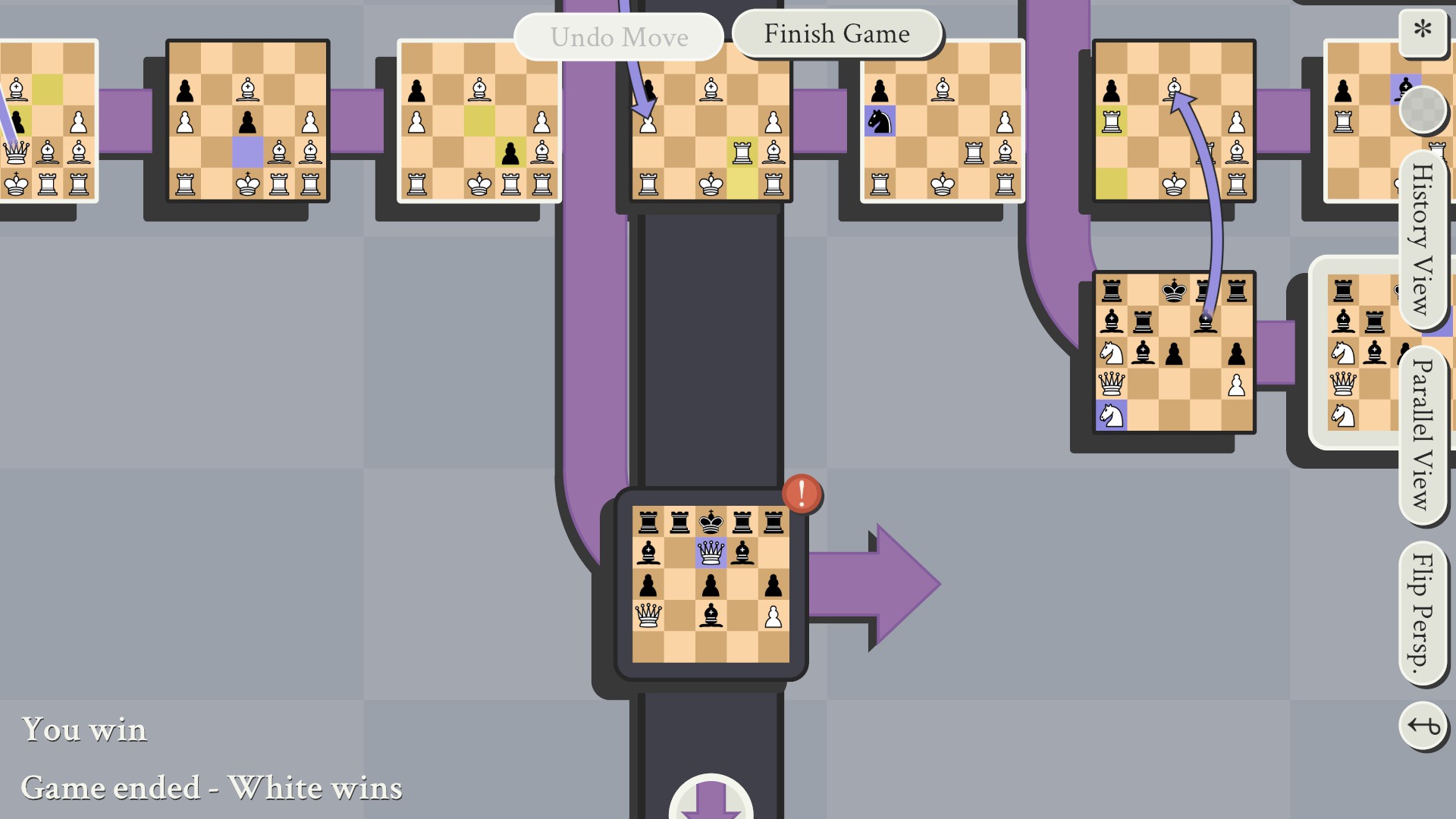

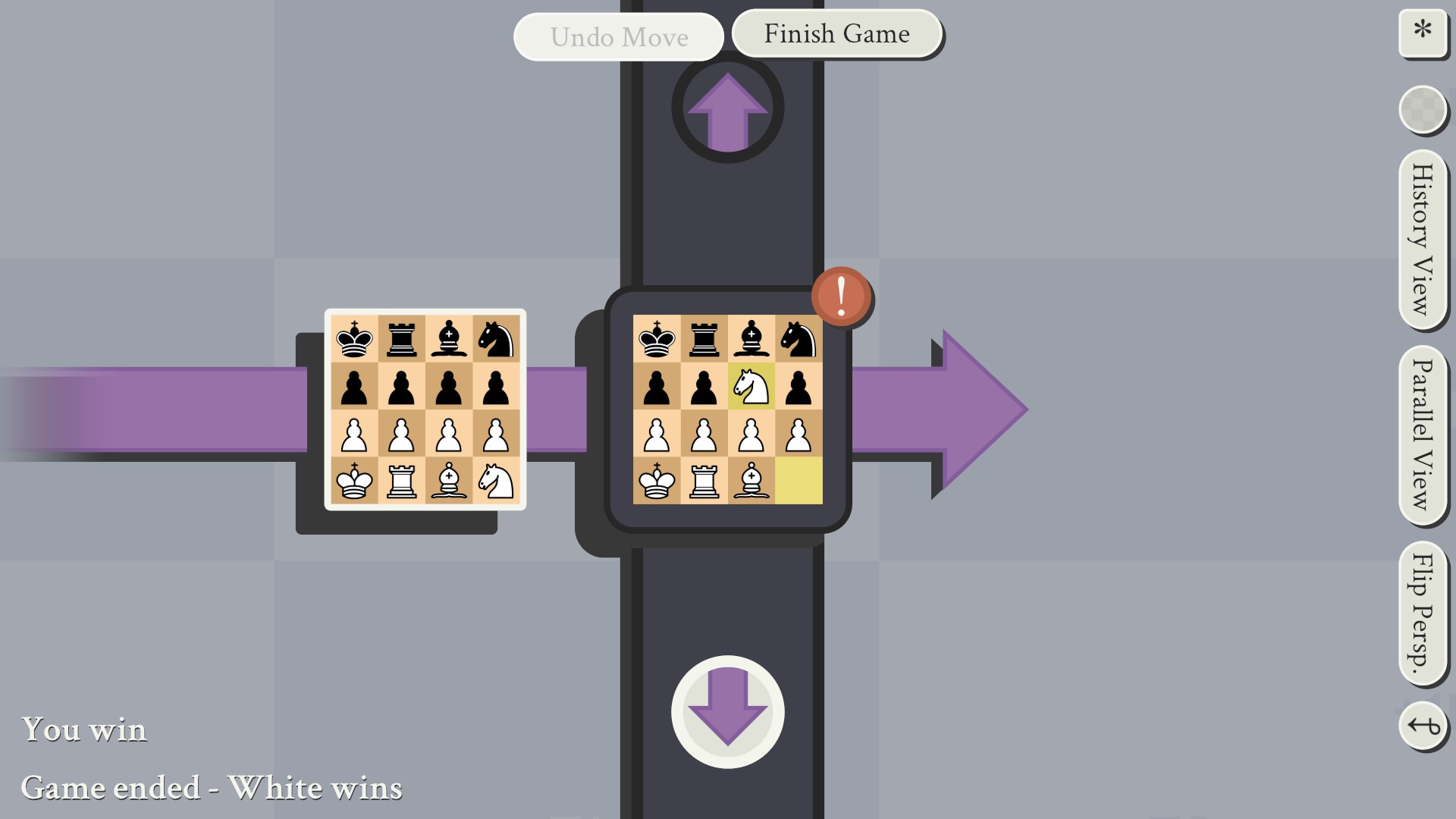

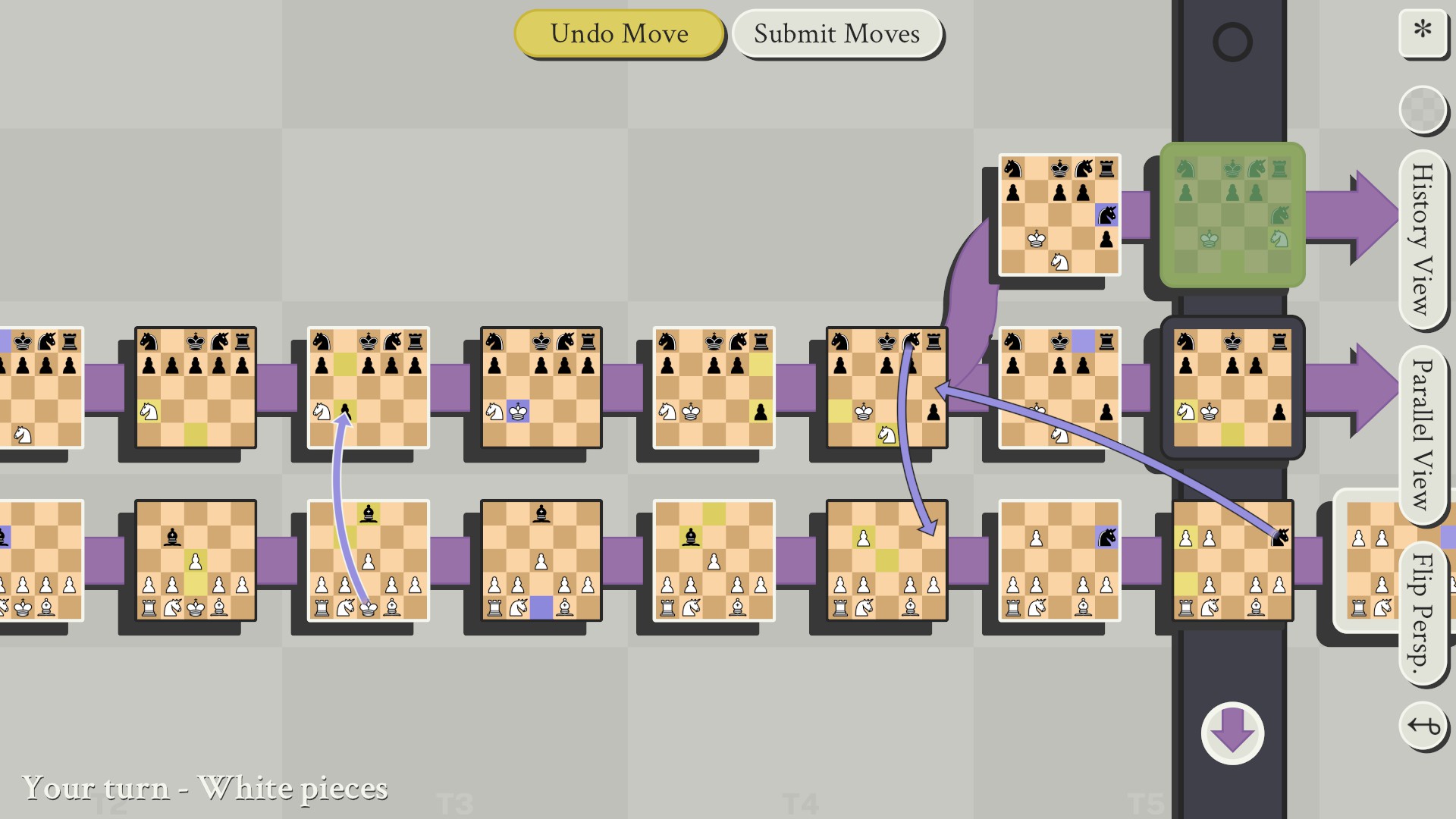

So what does this have to do with 5D Chess? Well, a key reason Chess is a strategic game is that accomplishing your goal of checkmate generally takes at least two pieces unless you can trap your opponent behind their own pawn line with a rook or queen. Add in that your pieces need to be moved into position without allowing your opponent opportunity to foil your plans, and you generally need to plan about four or five moves ahead to achieve checkmate. 5D chess usually involves checkmates with only a single piece, however, drastically reducing the amount of strategic planning required to achieve a win often down to just one or two moves. While the game still definitely rewards forethought in not leaving openings for your opponent to exploit, a player who is defensive and relies upon being an opportunist can often find an opportunity for an easy checkmate can fall into their lap without needing to actually plan for anything. The more fronts you open up by creating new timelines, the more you confound the ability for someone to make a dedicated long-term plan by opening up dozens of interconnecting factors that need to be weighed in any given plan, while the “sophisticated naive” strategy of just waiting for openings becomes more viable. This means that 5D chess games tend to be quite a bit shorter, favor a significantly different set of heuristics (which would force a master to learn this as an mostly new game), and ironically enough, is less strategic than normal chess by confounding long-term planning, while favoring pouncing upon short-term gains through heuristics. In fact, the computer opponent seems to be so confused by the number of permutations of possible moves when it tries to foresee the ramifications of moving into the past that even the “strong” scripts are apparently incapable of planning one full turn ahead! (The computer will apparently take as many as five minutes to think through a single turn when faced with enough timelines, however, so the sheer volume of permutations of moves to calculate may be impossible with standard brute-force methods, necessitating a “stupid” script. The script would still be much better served with a more sophisticated set of heuristics, however.)

Inversely, many of the game’s variants are much smaller and more constrained than standard chess (strangely, none of them actually use a larger board than 8*8 tiles), to the point that it actually devolves the game to below Tic-Tac-Toe levels of strategy, where the winner simply is whoever plays white, because they are so simple you can literally go through every permutation of plays and completely solve the variant.

Even in the variants that aren’t so badly designed white is almost guaranteed victory, most of the variants are so small and cramped that complex, multi-turn plans are unnecessary. Especially against the AI script, any reasonable strategy is unnecessary, because the AI is programmed to constantly try to put my king in check even if it’s a stupid move that will get the piece taken. The end result is that I can look at the board and try to formulate a plan that will advance my end goals, but the AI will ruin them with a continuous chain of stupid suicide attacks until I’ve eliminated all its units and I wind up getting a checkmate by just shoving a piece that already happened to be in position after taking a piece of the opponent’s into any of a half dozen positions that make for an easy checkmate of opportunity. Apparently, I was wasting my time actually trying to formulate a strategy in this strategy game, because it’s designed to limit the capacity for you to think strategically at every turn, and I should just be in permanent reactionary mode until I get into a position where a win is handed to me simply because I could look exactly one move ahead and avoid the obvious checkmates.

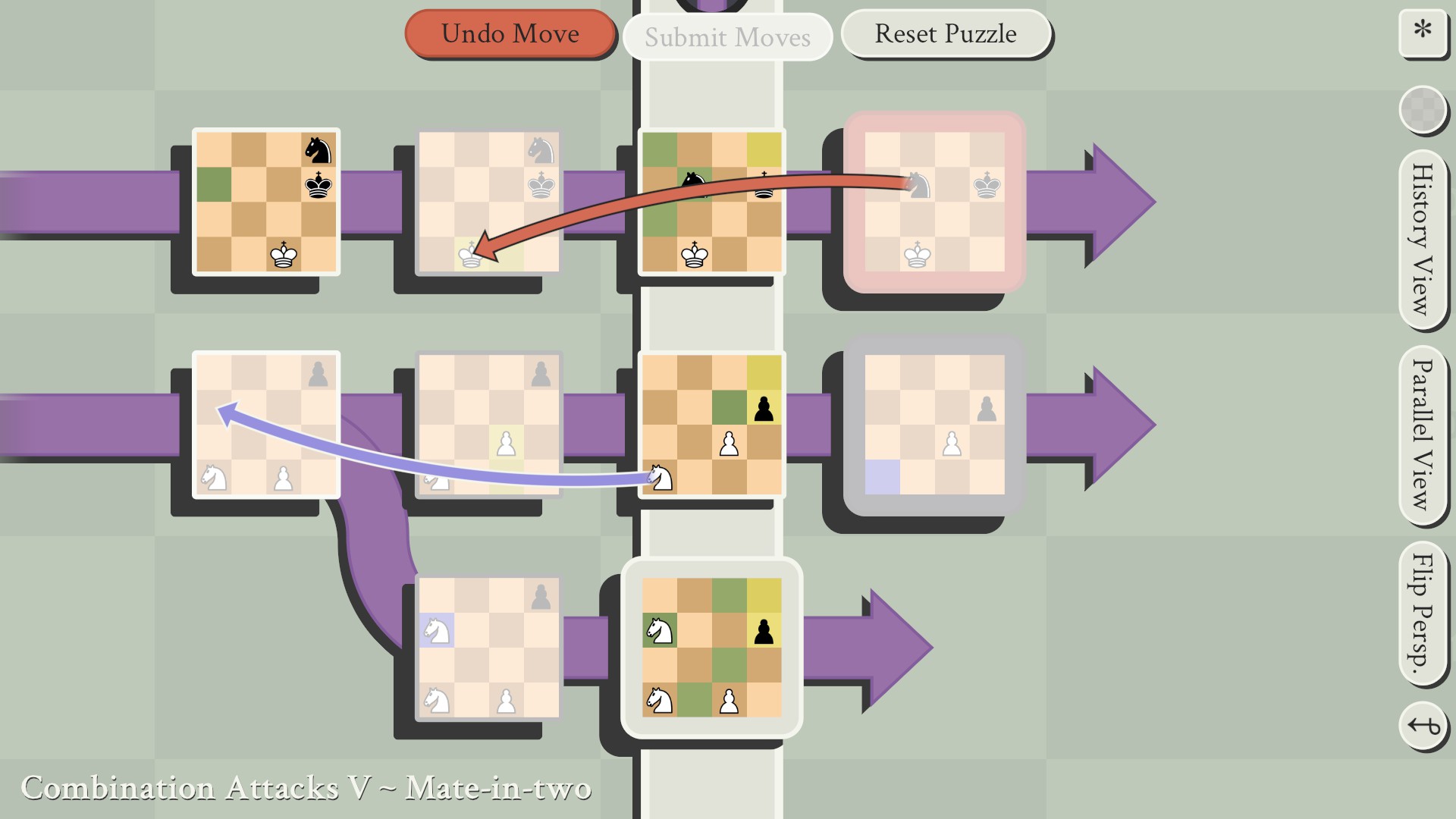

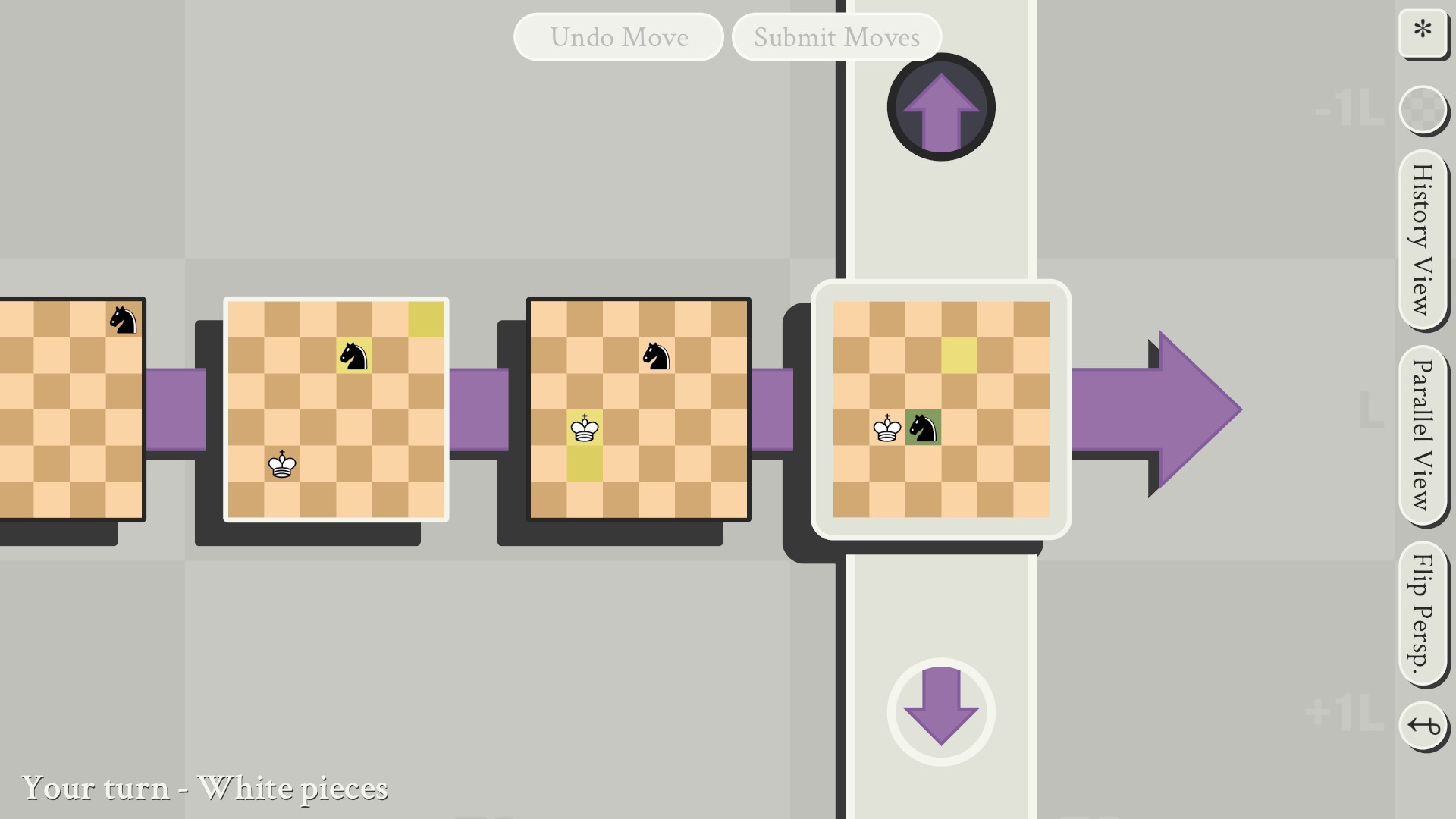

An Example Turnabout

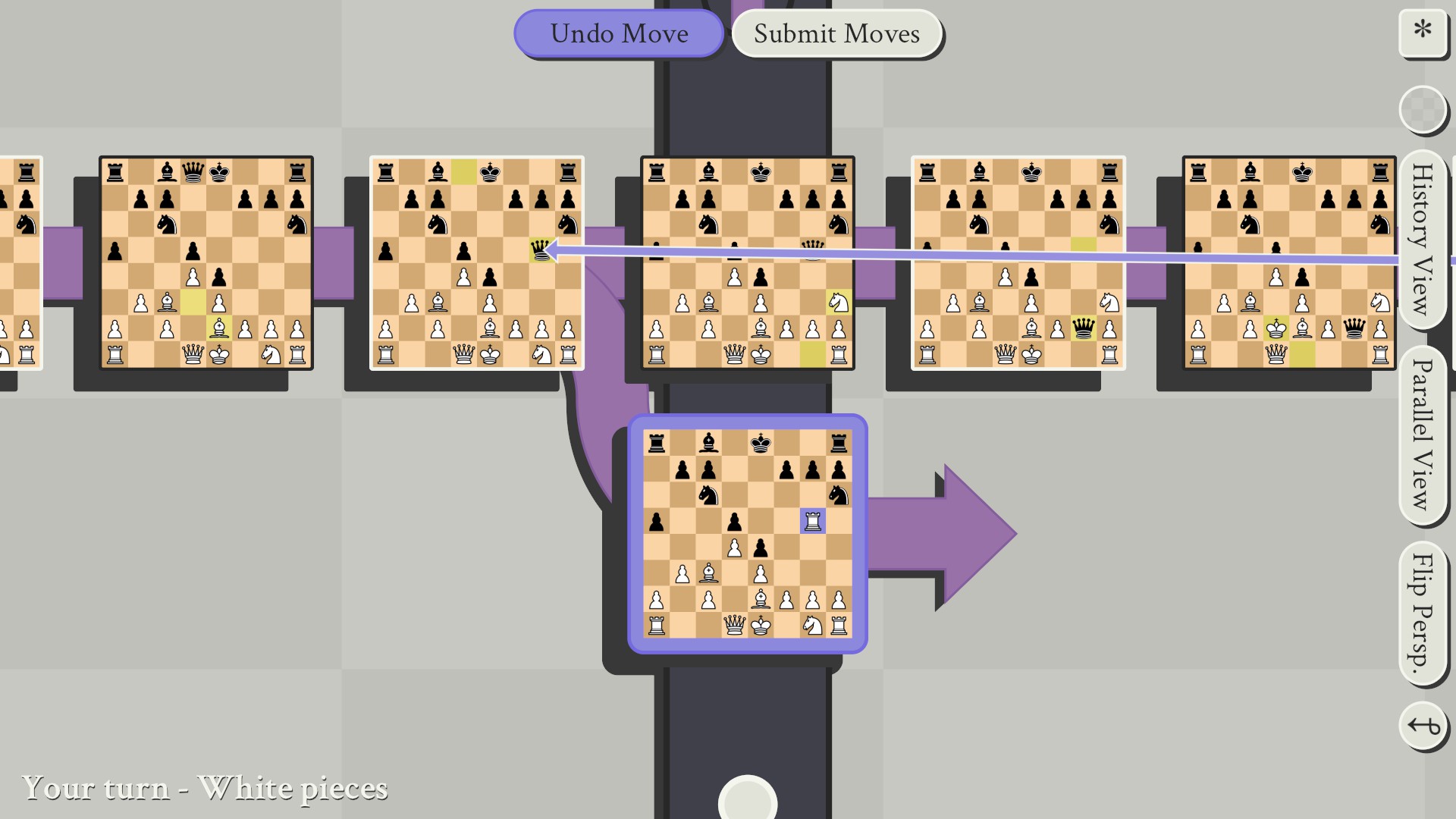

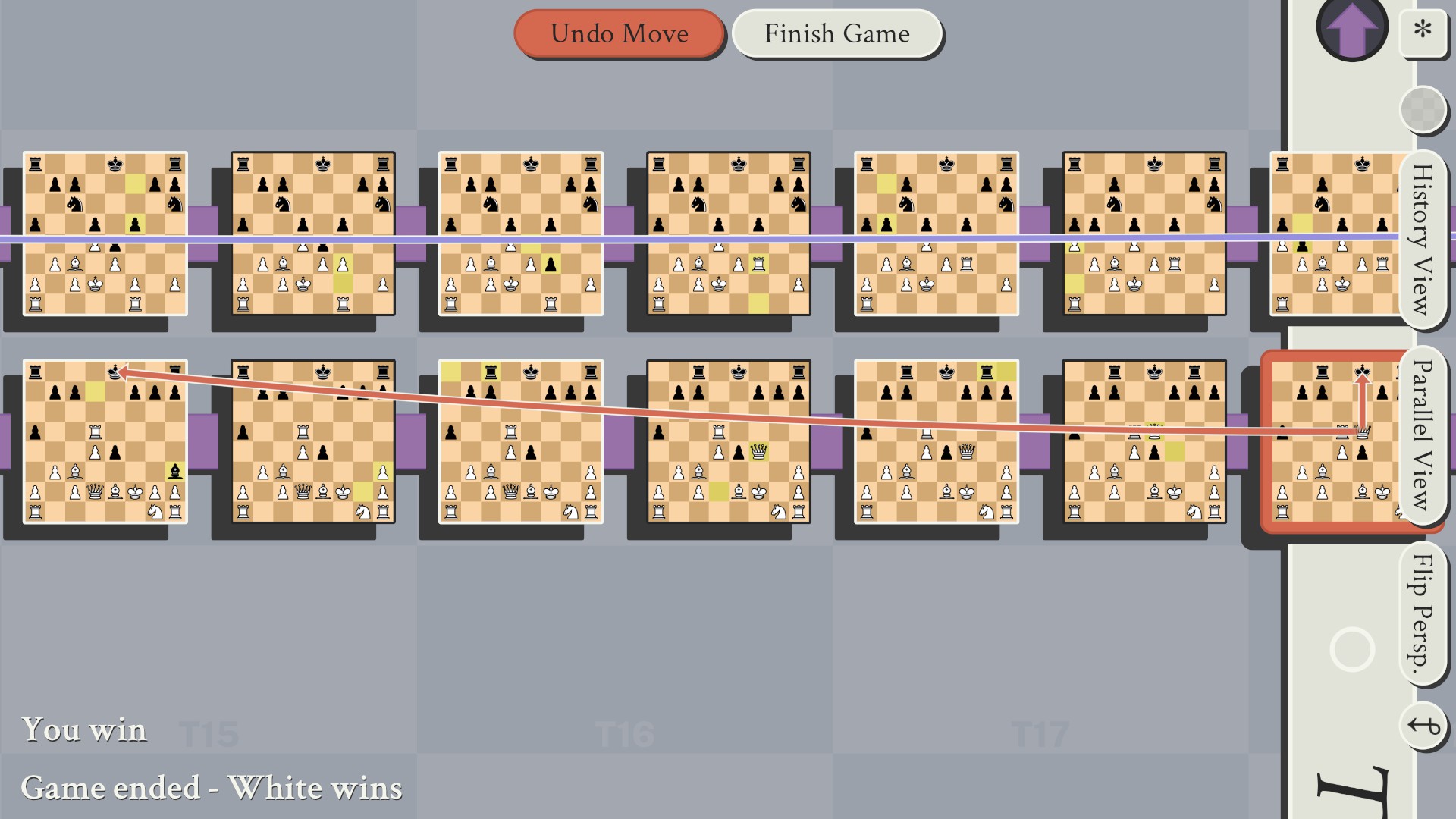

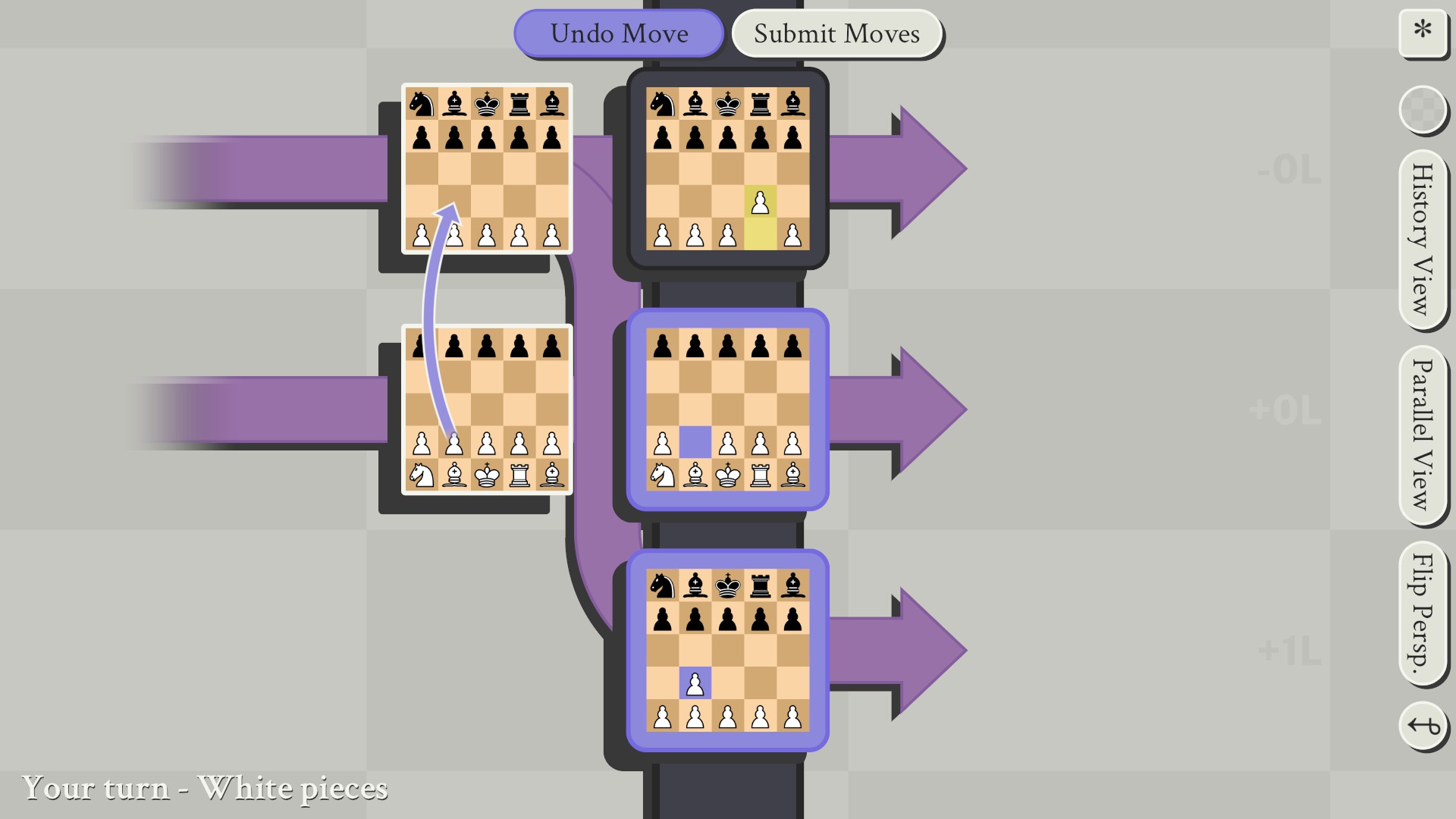

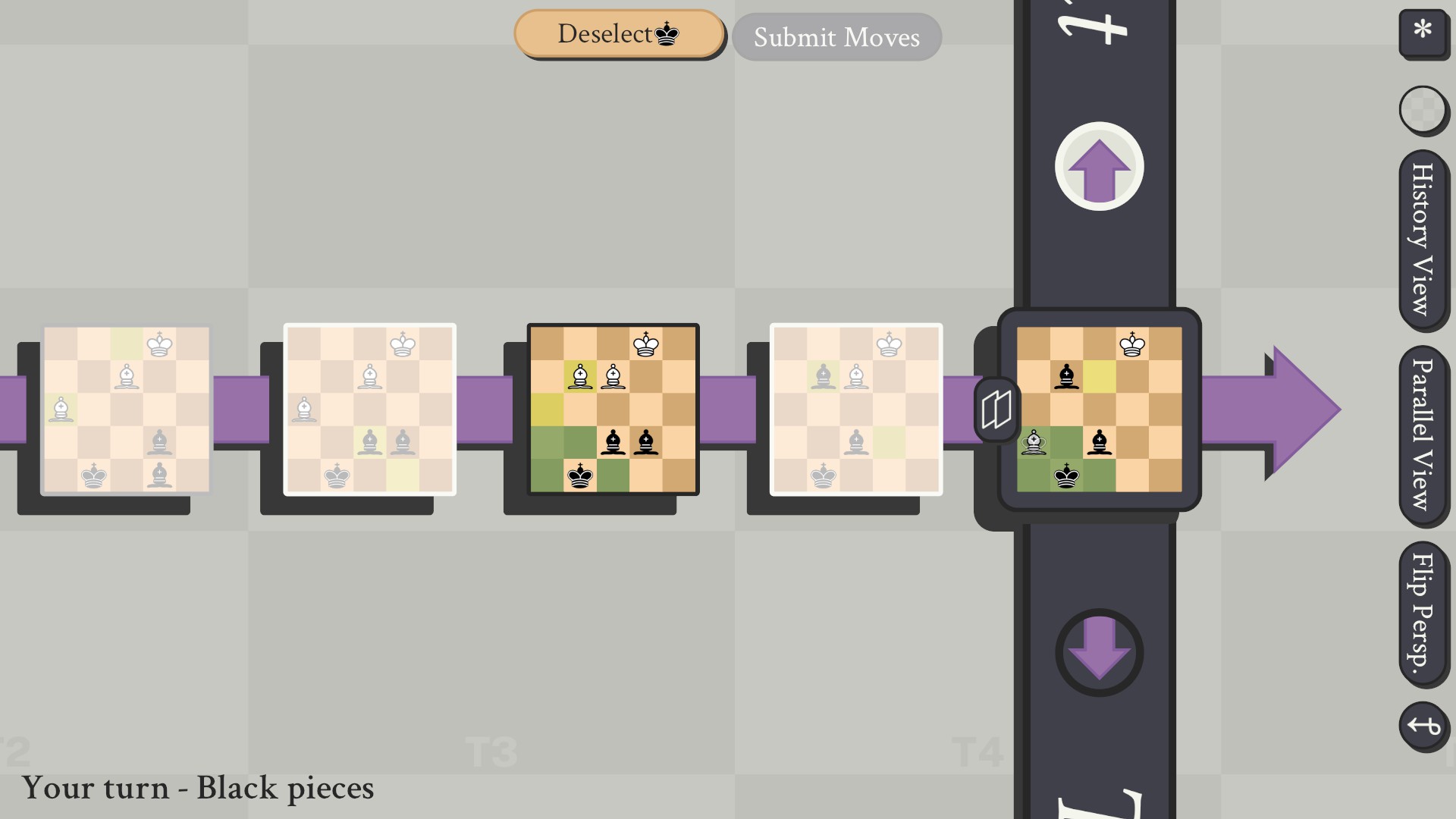

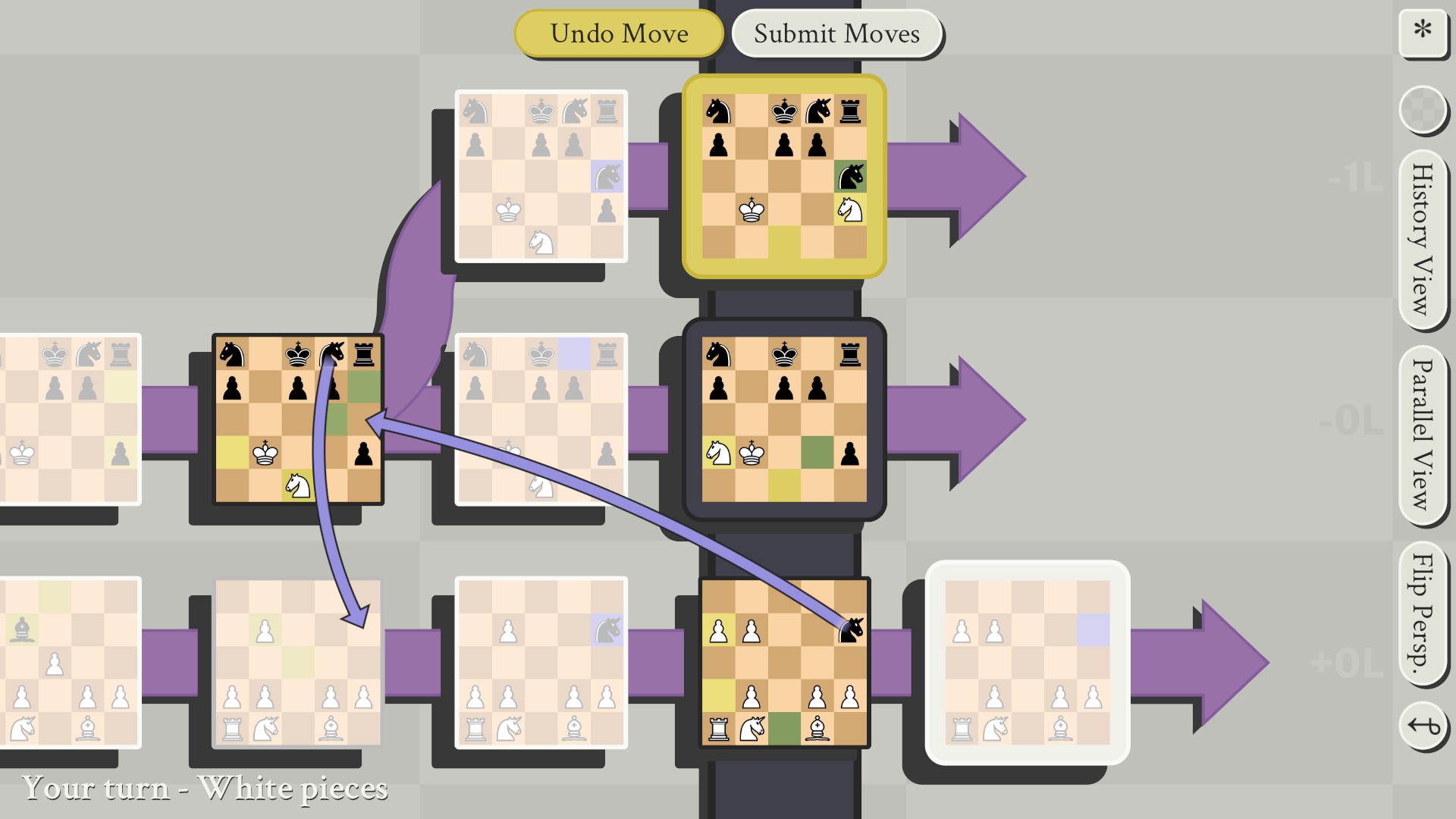

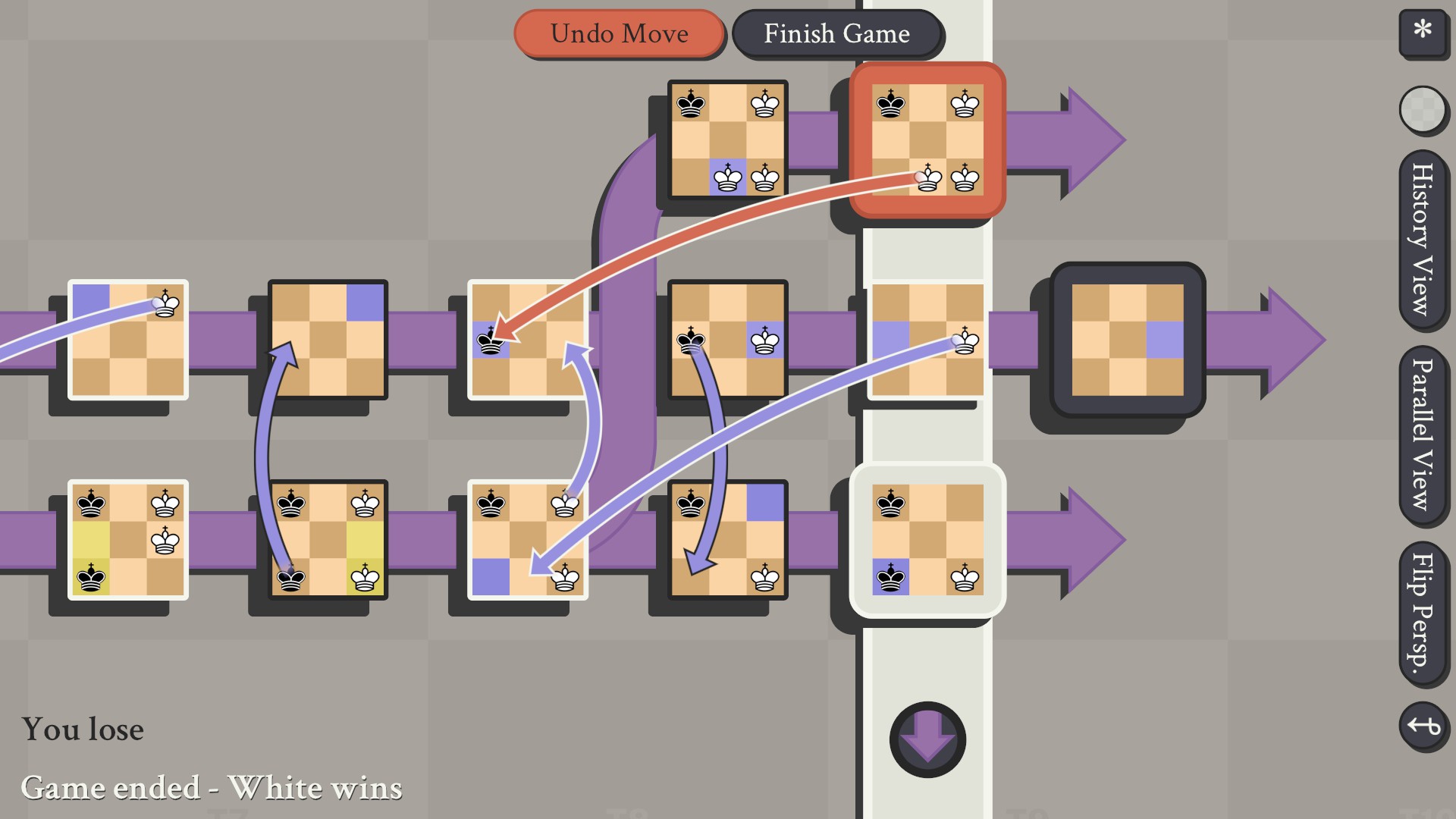

So, I’ll admit I’m not a great Chess player. I played on the Chess team in middle school (nerd cred!), but haven’t played in nearly two decades. Hence, even though the AI is dumb as bricks, it can still force me into a weak position when I don’t take enough care. In this game I was playing mostly as a standard game of Chess, I had been hesitant to trade queens, and therefore was pushed into an exchange of pieces that left the opponent at a slight advantage in pieces and position… if this were normal Chess.

While normally, playing just plain Chess can easily lead to wins against the fairly weak AI (even when on the “strong” settings, it makes alarmingly poor choices), and it’s easy to create situations where going back in time hoists you on your own petard, but now that I was in a weak position, I started to look for a way to use time travel to my advantage long-term.

Watch carefully, because I’m about to do what’s called a “pro gamer move.”

So… am I good or bad at this game? Well, I’m definitely rusty at Chess if I’m making foolish moves like the one that got me into this mess in the first place, but at the same time, it only took a three-move plan to get back in time to reverse my fortunes, and I was fortunate enough to be in a place where the opponent couldn’t make good moves to interrupt my plan even if it could foresee them. I also was aware enough to follow the heuristics to avoid obvious (to someone used to the game) pitfalls that create one-turn mates, like keeping units in front of my king to avoid time-traveling bishops and letting the bishop or pawn be in places to take the attacking knight.

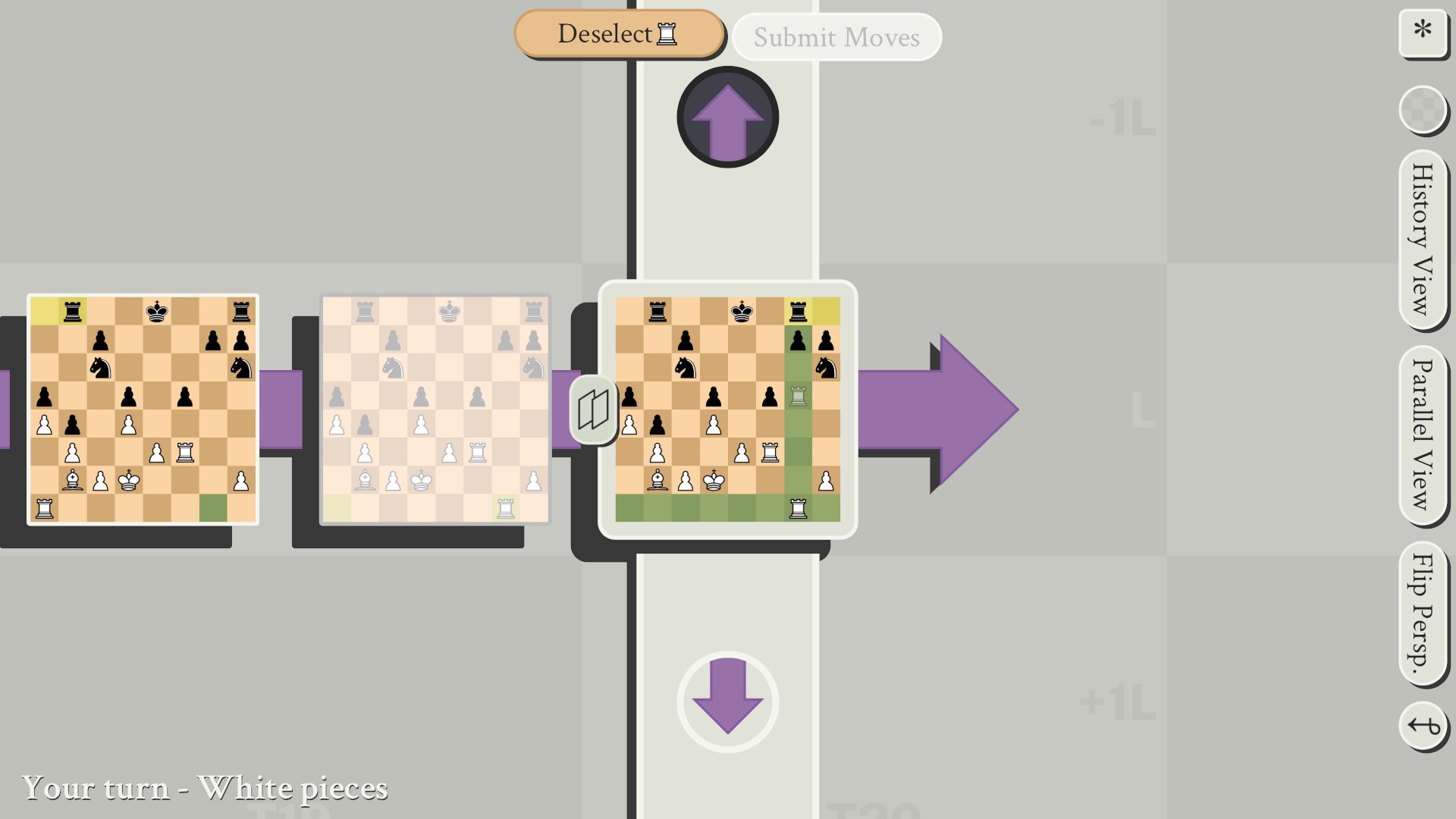

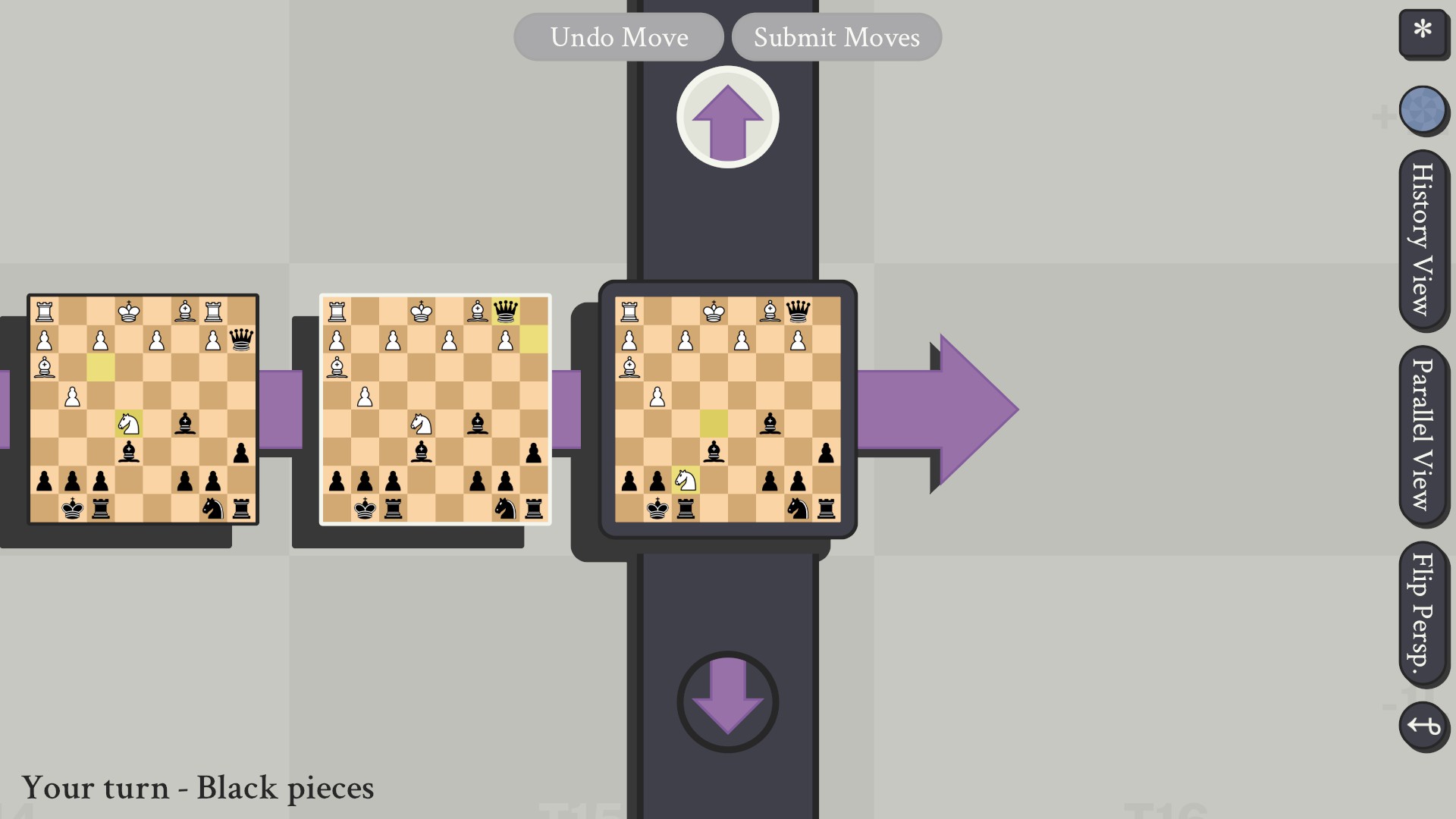

Essentially, this is the problem that causes 5D chess to be less actually strategic than standard 2D chess – multi-dimensionality confounds the ability to plan significantly further ahead by making accounting for every permutation significantly harder (which isn’t helped by a bad interface hiding the boards).

So… What Is Going on Here?!

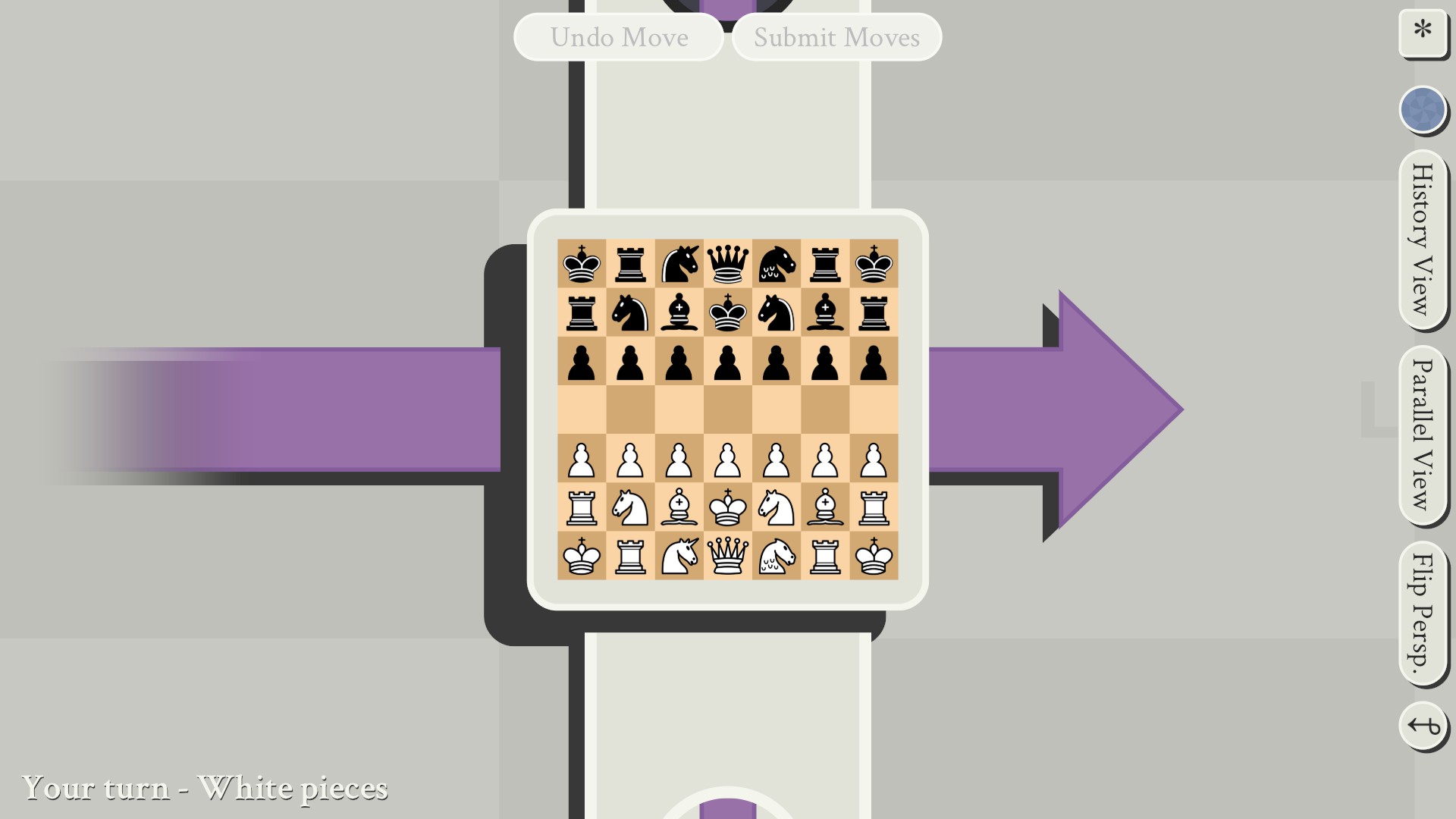

This game is hard to understand not just because of its concept, but also because the game itself literally only has a text file for rules that suggest you should go to the official Discord to ask questions about the basics, or maybe Google some guides to learn. Hence, allow me to do the developer’s job for him, and give you a quick rundown of the rules so you won’t be as lost as I was trying to learn the basics.

The main conceit of 5D Chess is that all the pieces move along some minor variation of their normal movement, so that you can generally still play standard 2D chess up until someone decides to go back in time.

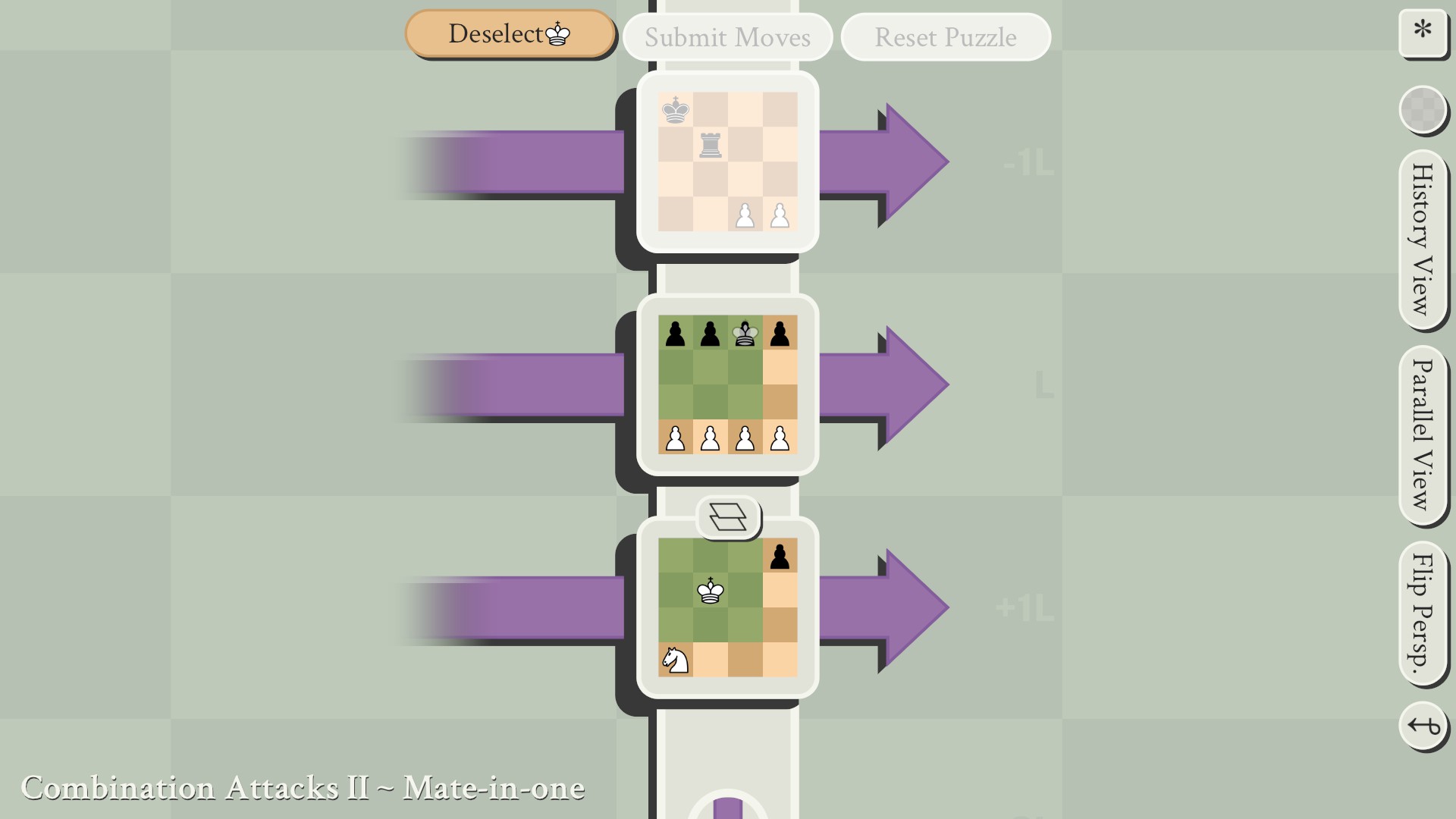

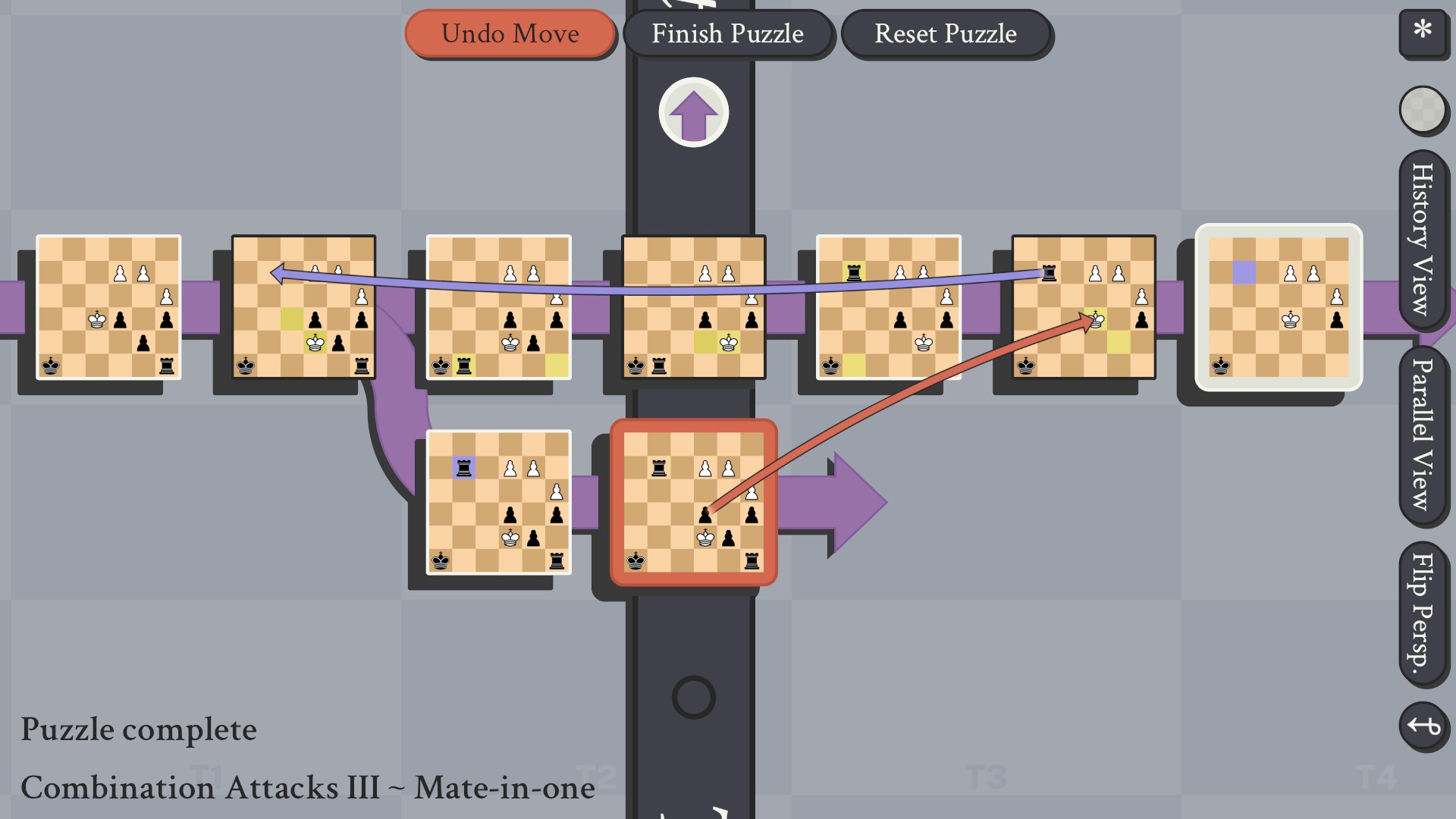

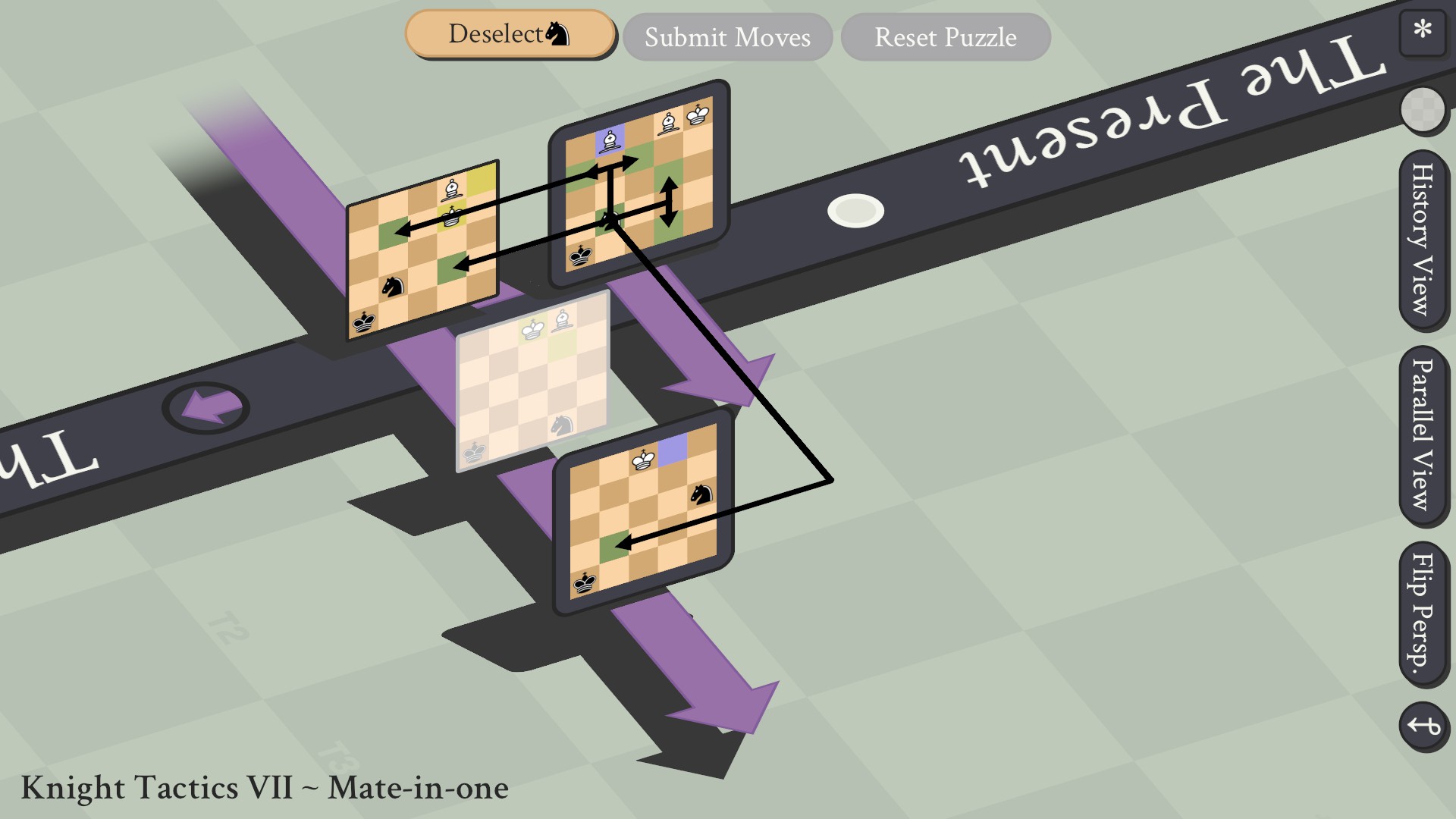

Here is a list of the major rules changes in 5D Chess (“spoiler” warning – I’m going to use some of the puzzles as examples for these rules, giving away some solutions, because the puzzles are basically the tutorial for this game, and the grotesques that they set up demonstrate the rule more clearly and conveniently than a random screenshot I already had taken outside the puzzle mode.):

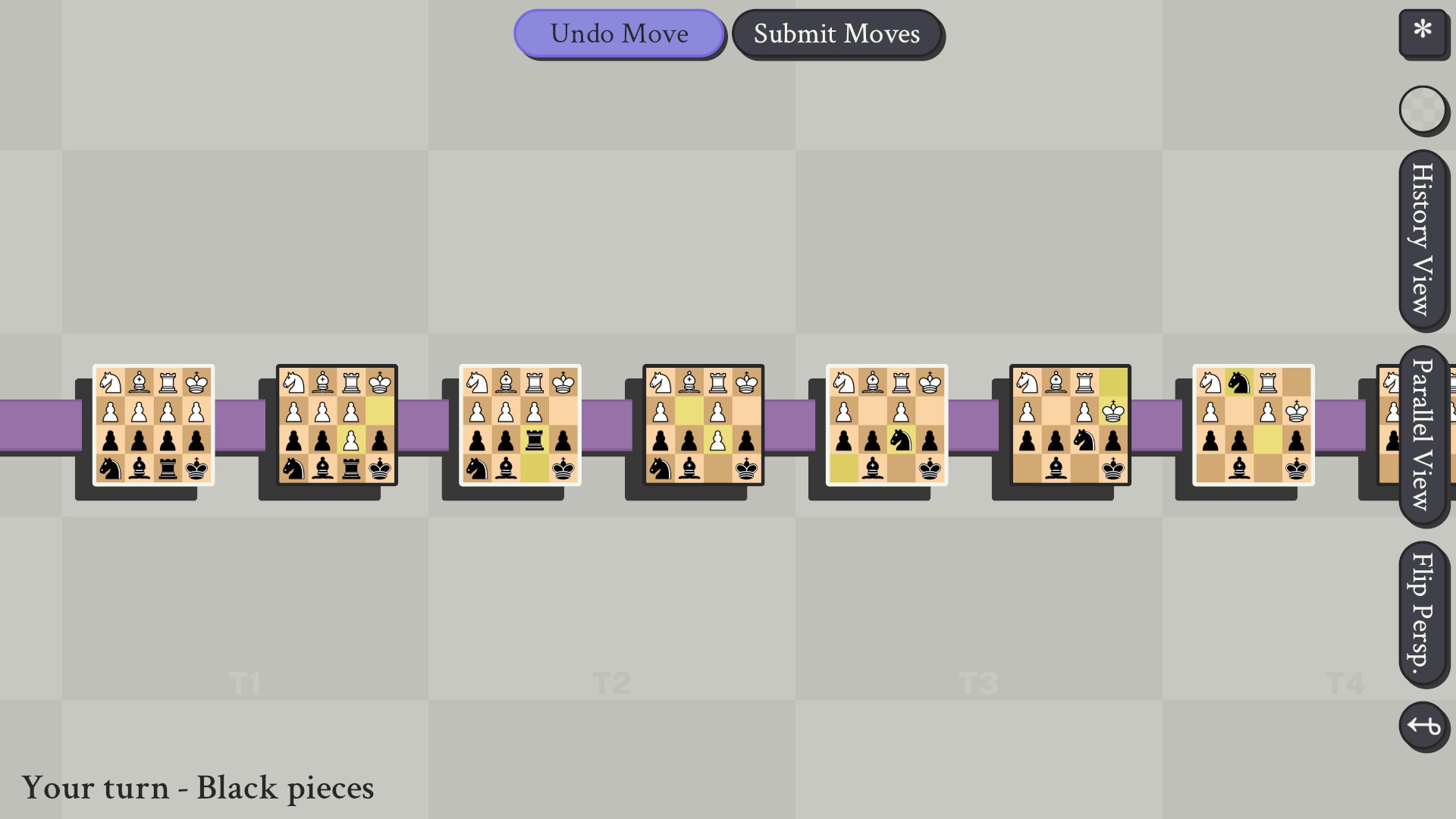

1. Time is measured in discrete units, where one time… tile(?) is measured as both your move and your opponent’s move. Meaning, you can only move back onto the board in the state where you were about to make your move, and your opponent’s move time slices are not counted. (This means you have to ignore half the boards along the timeline. Each board has a black or white frame to denote whose turn that board is on, and only boards of your color on the timeline count as spaces in time when you are moving pieces.)

2. To win (or lose), you (or your opponent) only need to get a checkmate against any one king anywhere along any timeline or dimension. (Apparently, only dead kings cause temporal paradoxes in time-traveling chess land.) Some variant modes of the game even feature multiple kings from the start, and putting any one into checkmate is a victory or loss.

3. “The past can’t be changed.” This means that you can move into the past, but as soon as you do, it creates a divergent timeline/parallel dimension, which forks off from the original. (In effect, in the original timeline, the piece just disappeared in that timeline, and you have to keep playing without it. However, the timeline you created will now have another copy of the piece you moved through time. In some cases, this is a way to get an advantage in numbers against an opponent!) (Also, going into the past to create checkmate is still allowed, as the new dimension would still count as a checkmate and end all other parallel dimensions because of the previous rule.) This also means that pieces on boards where a move has been played (in the past in that timeline) cannot move even if threatened by pieces on another timeline, such as one created by going back into the past.

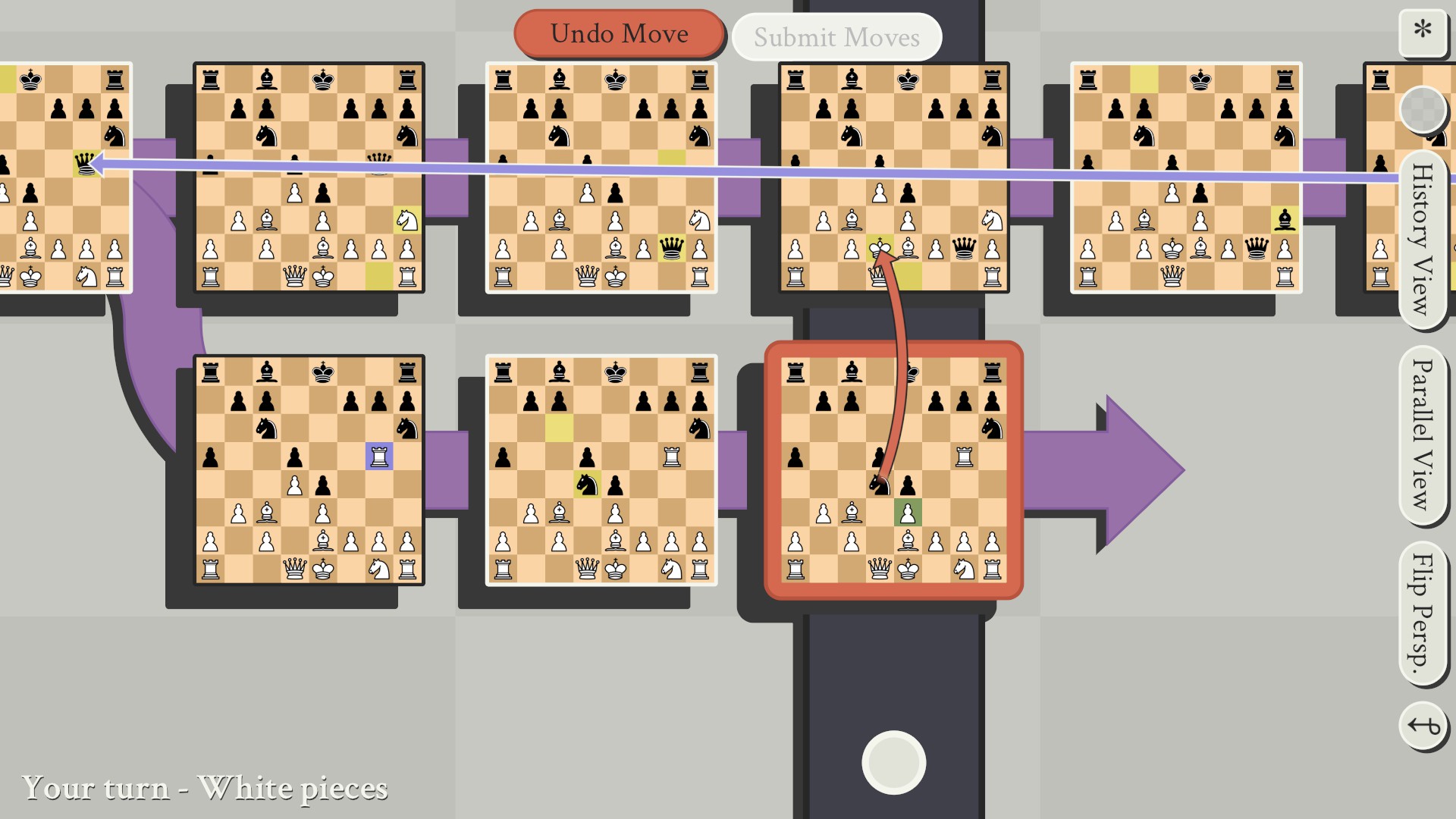

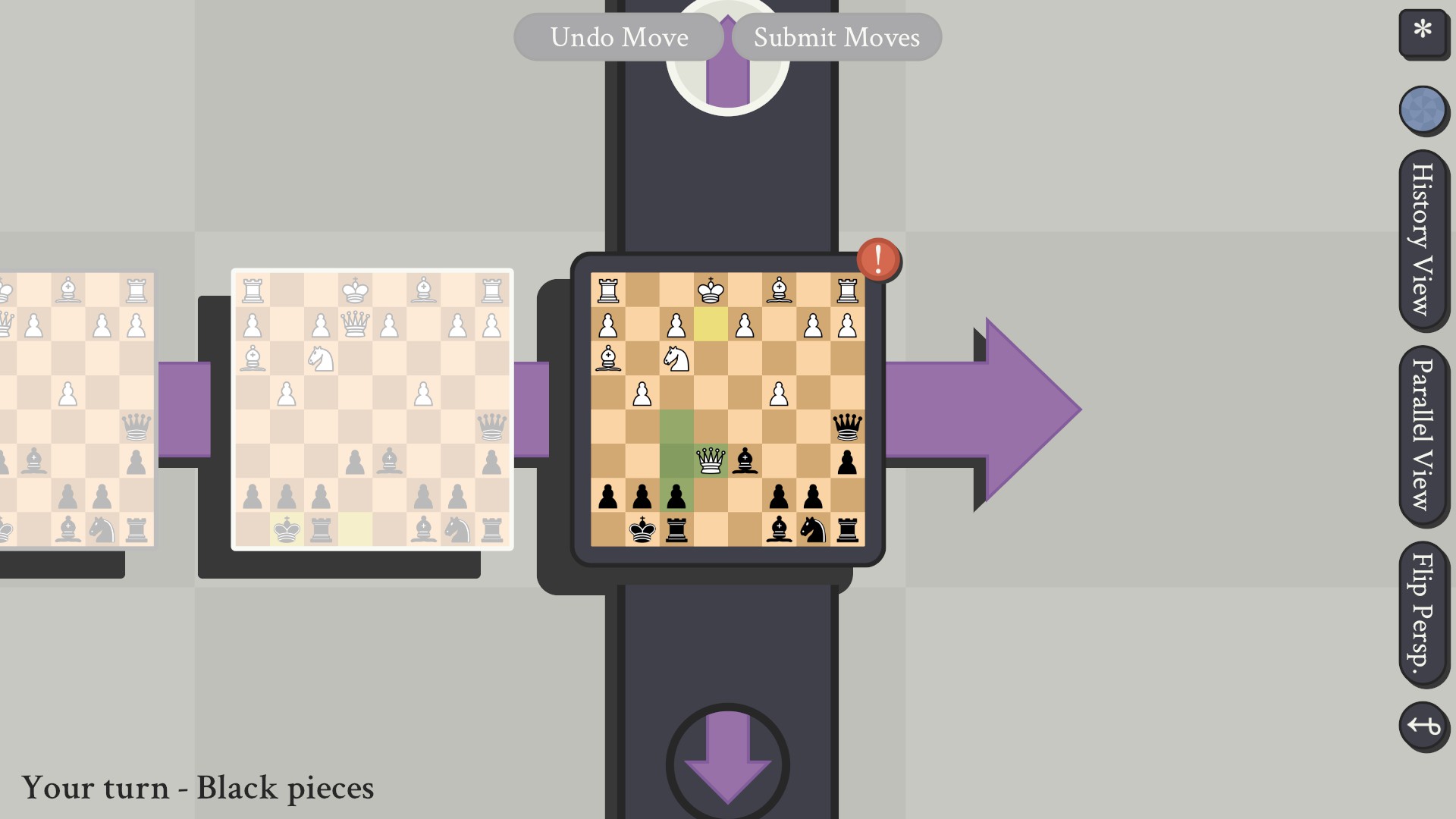

4. In normal Chess, when in check, you have three options to avoid checkmate: a) move the king out of check, b) interpose a piece between the threatening piece and your king, or c) take the threatening piece. If a king is threatened in the past, however, because the past cannot be changed, only c, taking the threatening piece (or another option I’ll get into a few rules later) is available as an option. (Even if going back in time to interpose pieces, that just splits the dimension and leaves the original dimension where the king is captured still in place. Hence, like Hitler’s bodyguards in science fiction, you have to always be on guard against leaving openings that a time-travel assassin can slip through, because once it happens, it’s already too late to stop it.) This means that getting checkmate by moving back in time is extremely effective, to the point of 5D chess games actually tending to be finished in many less turns simply because it only takes a knight being two squares away from a king or a bishop being in a horizontal or vertical line with a king that hasn’t moved in the past few turns to get a checkmate.

5. Pieces can move only to boards that are in existence already. This generally means it’s impossible to time-travel forwards (except through the usual “waiting for time to advance normally”), because there is no board in the future for you to move on… unless there’s another dimension that is further forward in time you can move onto.

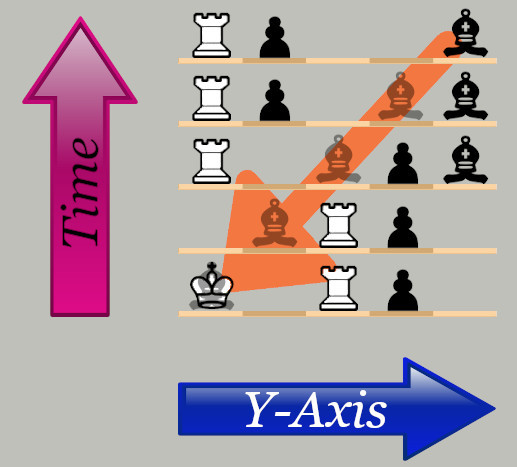

6. The movements of pieces are redefined as moving through a set number of dimensions a certain distance. For example, a bishop doesn’t move “diagonally” in 5D chess, it moves “equidistantly through two dimensions.” In the standard two dimensions on a board, this still results in apparently diagonal movement, but bishops can also move along the horizontal axis, as well as backwards through time, effectively “diagonally horizontally and through time,” allowing it to put a king in checkmate by moving two tiles along the X-axis and two tiles along the T(ime)-axis.

7. Pieces need to have a clear line of movement along the time axis just as they need to have a clear line along the X or Y axes, meaning that, for example, the pawns in front of the king at the start of a standard game will block movement through time the same way that pieces besides the knight cannot move through pieces in the standard two dimensions. (A bishop would have to go back in time and take the pawn in front of the king, and then allow the opponent a chance to move to get the king out of check.)

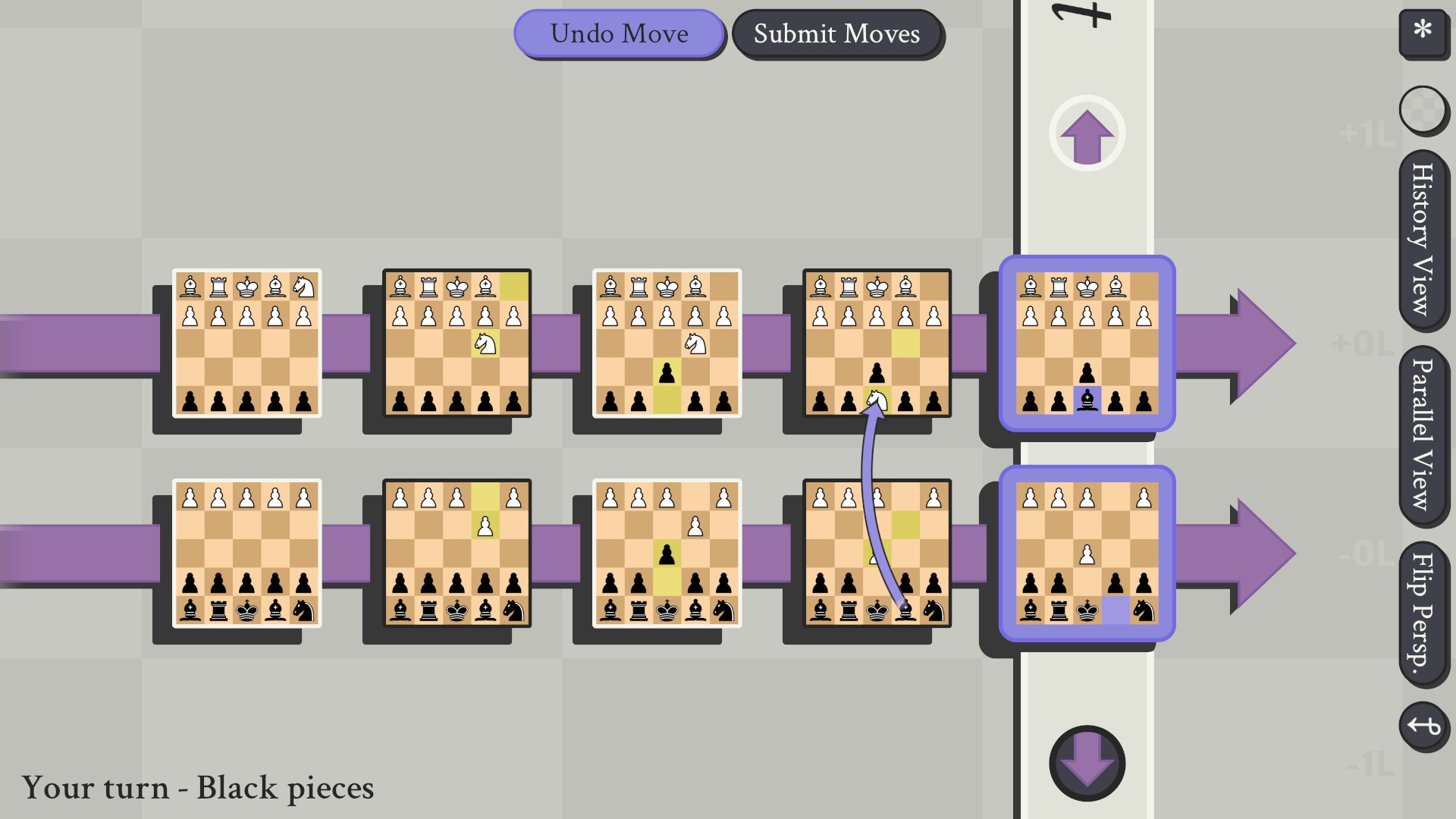

To demonstrate how a bishop moving through time can be tricky, let me show an example:

Allow me to make a diagram just to show you how this actually works, because it’s not very easily apparent how it worked. (This lack of apparent cause is why I didn’t realize this was going to happen and was caught in checkmate in the first place…)

This means that defending your king from time assassins is actually very tricky and unintuitive.

Further, in the case of the rook, the rook can only move through one dimension at a time, and therefore has to move along the time axis while landing on the same square in the X and Y axes. This means if you want to move the rook back through time, you must move the rook the turn immediately beforehand, because otherwise the rook will be blocked by its own past self standing in that spot.

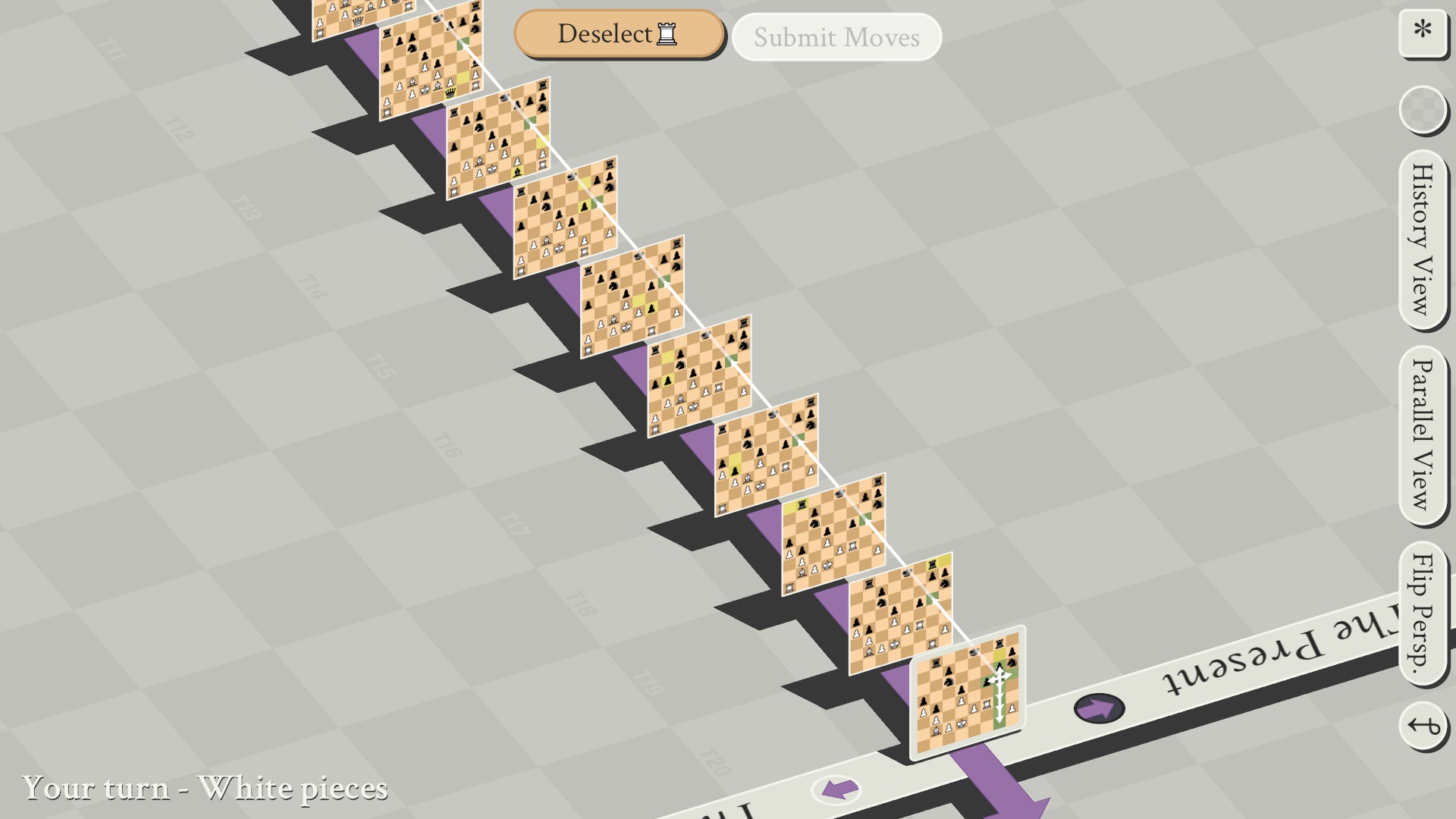

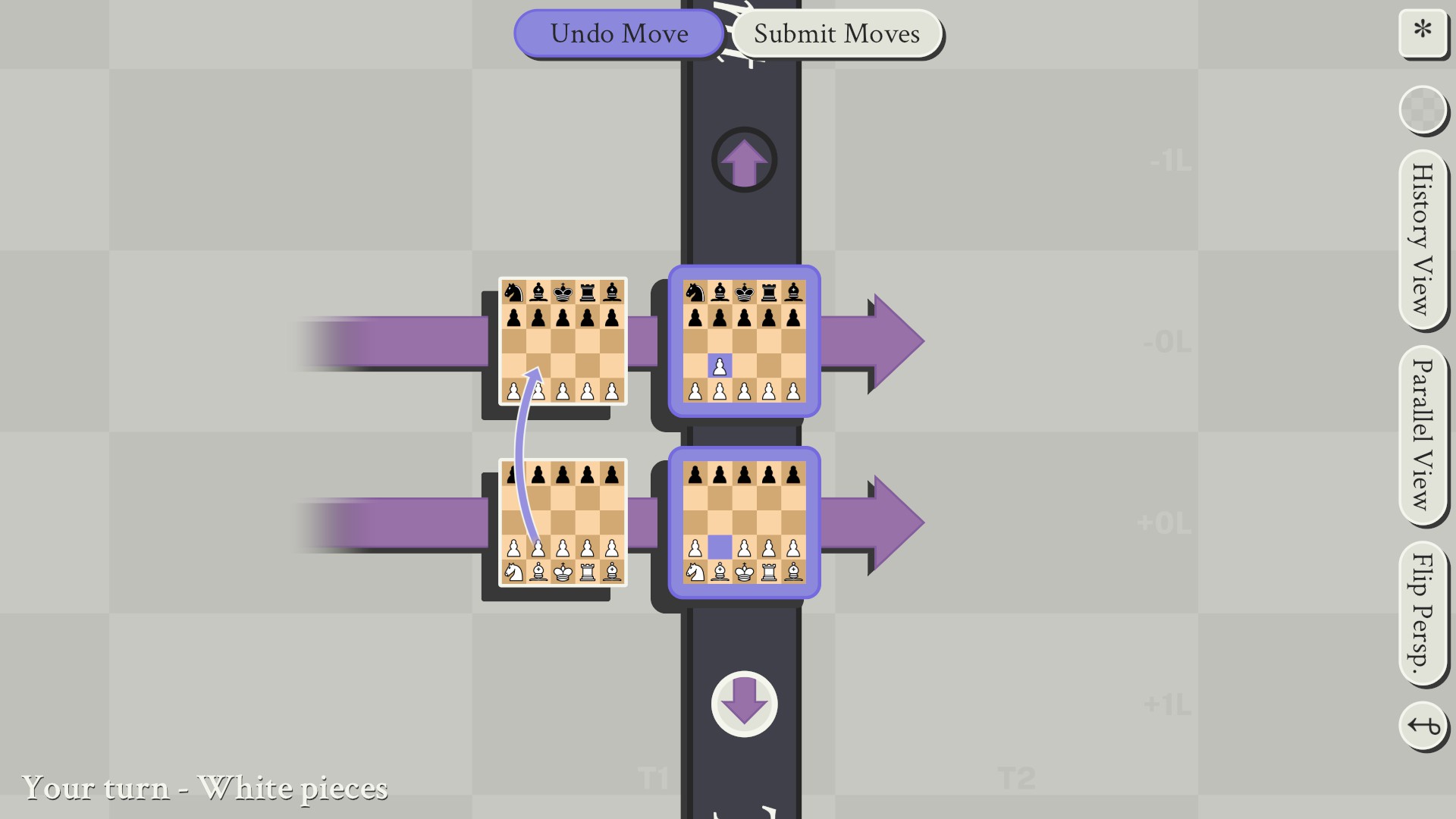

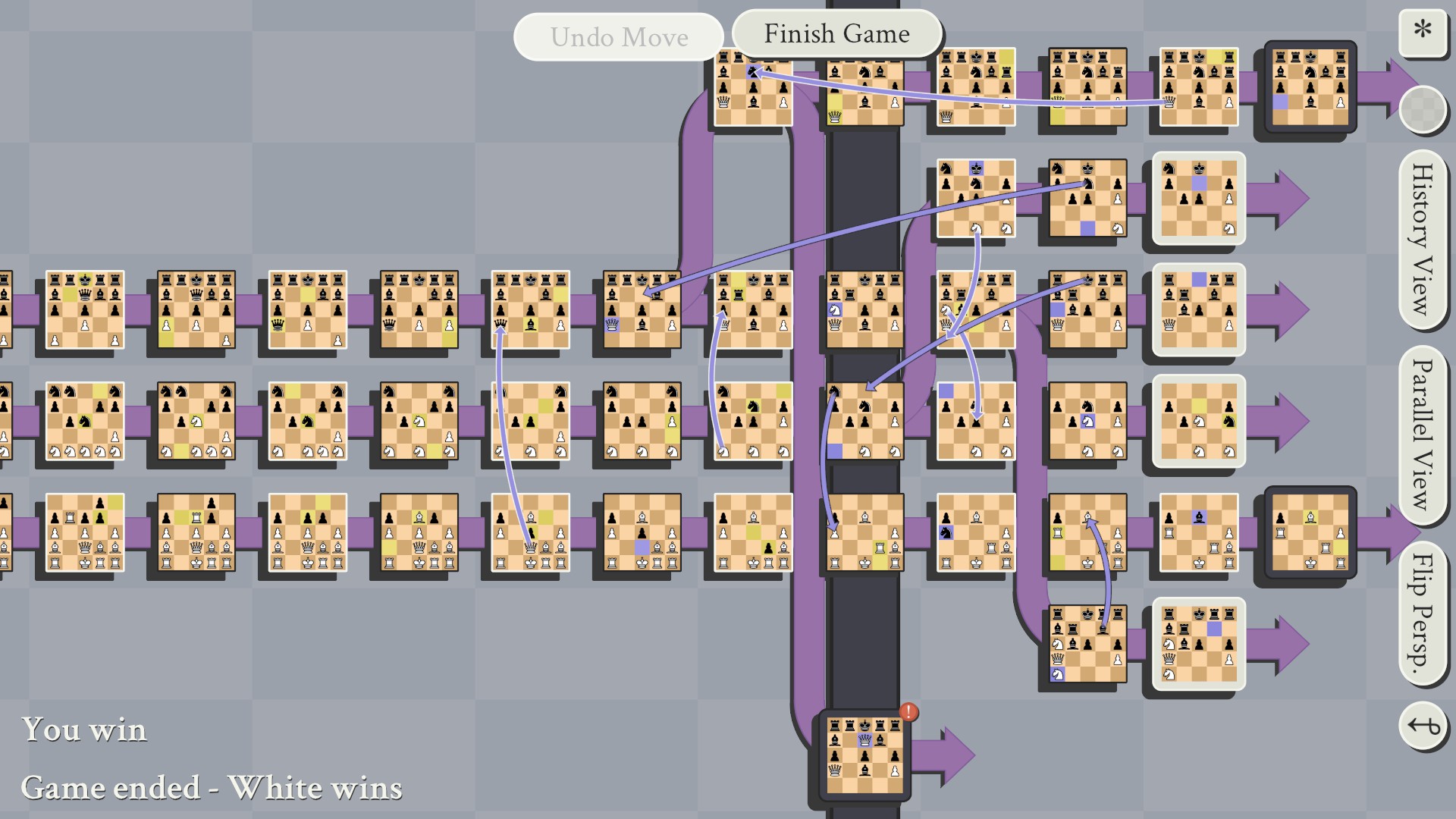

8. In the background, there is a bar that says “The Present” on both ends. When going back in time to create a new active parallel dimension, it will move The Present bar backwards to that point.

9. You can only create as many ACTIVE parallel dimensions as your opponent has created plus one. Meaning that if your opponent has created no divergent timelines, then you can still create more timelines (by sending pieces back in time), but these will create inactive timelines. This is represented by purple arrows on the “The Present” bar indicating which player can create active timelines. Active timelines have purple arrows behind their boards indicating their progress and from whence they diverged. Inactive timelines have either white or black arrows under their boards. (The existence of this rule seems to exist to prevent profligate dimension-creation.)

10. Dimensions/timelines can be moved through the same way that other dimensions can be moved through. Kings, for example, are capable of moving exactly one space in any number of dimensions at the same time, so a king can move one space right or left, forward or back, back in time, or across adjacent timelines. (Timelines are laid out so that the timelines created by the player are on that player’s bottom of the screen, as by default the whole interface reorients to put your color’s side on the bottom of the board and the opponent’s side at the top, and timelines are arranged the same way. This means if you are playing black, your opponent is at the top of the board and new timelines created by white creating a new timeline will appear to be added on top of all existing timelines, while new timelines you create are added to the bottom, and it will appear the opposite to your opponent.)

11. Calling back to rule 4, there is a new way to evade checkmate, which is to go back in time before the threatening piece can go back in time itself (when you can create an active timeline), and thus force “The Present” bar back to before when the checkmate will occur. This forestalls checkmate until The Present bar advances to where it forces a move on the board giving the threatening piece a chance to move (back in time). Effectively, you have that many turns to either take the piece (at the exact moment before it can go back in time – it’s useless to take the piece early, as that just creates a divergent timeline and leaves the original piece alone) or else you must checkmate the opponent in that many turns in the new timeline you created. (Again, a reason you have a limit on creating active timelines is probably to stop players from creating arbitrary amounts of extra time by constantly creating new parallel dimensions.) You also cannot go back in time on the timeline where the threatening piece is located, as that would then still give a turn to your opponent because of the wonky way the rules work. I cannot stress enough that this is not explained anywhere in the game, and even asking other players, I had to go through several people to find one who knew.

12. You must play a move on every board/timeline that is in the present that hasn’t already been played. (Moving on future boards or inactive boards is an option, but not required to pass the turn to your opponent, and you cannot take another turn until they have made their move on an inactive or future board.) Moving a piece from one timeline to another counts as your move for both boards. This means that if you play a move on one timeline, then move a piece from another timeline into that timeline, it will actually create a new branching timeline, because it becomes “the past”, while if you do the dimensional travel before (in player time) moving, it will prevent making another move.

13. If you have no pieces that can move on a board, it will be a stalemate or your loss if you are in check in any timeline without the ability to move on a timeline (even/especially if they are different timelines), so you might be forced to move pieces between dimensions, as not moving when it is possible to move is illegal.

14. Pawns are a special case, which can only move as per normal 2D chess, or “up” timelines for the player or “down” timelines for the opponent. (The timelines, like boards, change orientations depending upon the player’s color.) Capturing “diagonally” can be accomplished as normal, but if going through dimensions, you can also move the pawn onto the same position on the board, but back in time (helpfully, left a pair of boards on the screen) as it moves across timelines (up on the screen).

15. Queens can choose how many dimensions they move through at a time, from one to four dimensions at once, making them dramatically more powerful than they already were. (You should make eliminating the opponent’s queen by any means necessary a top priority, as a time traveling queen can gain checkmate in an alarmingly large number of ways.)

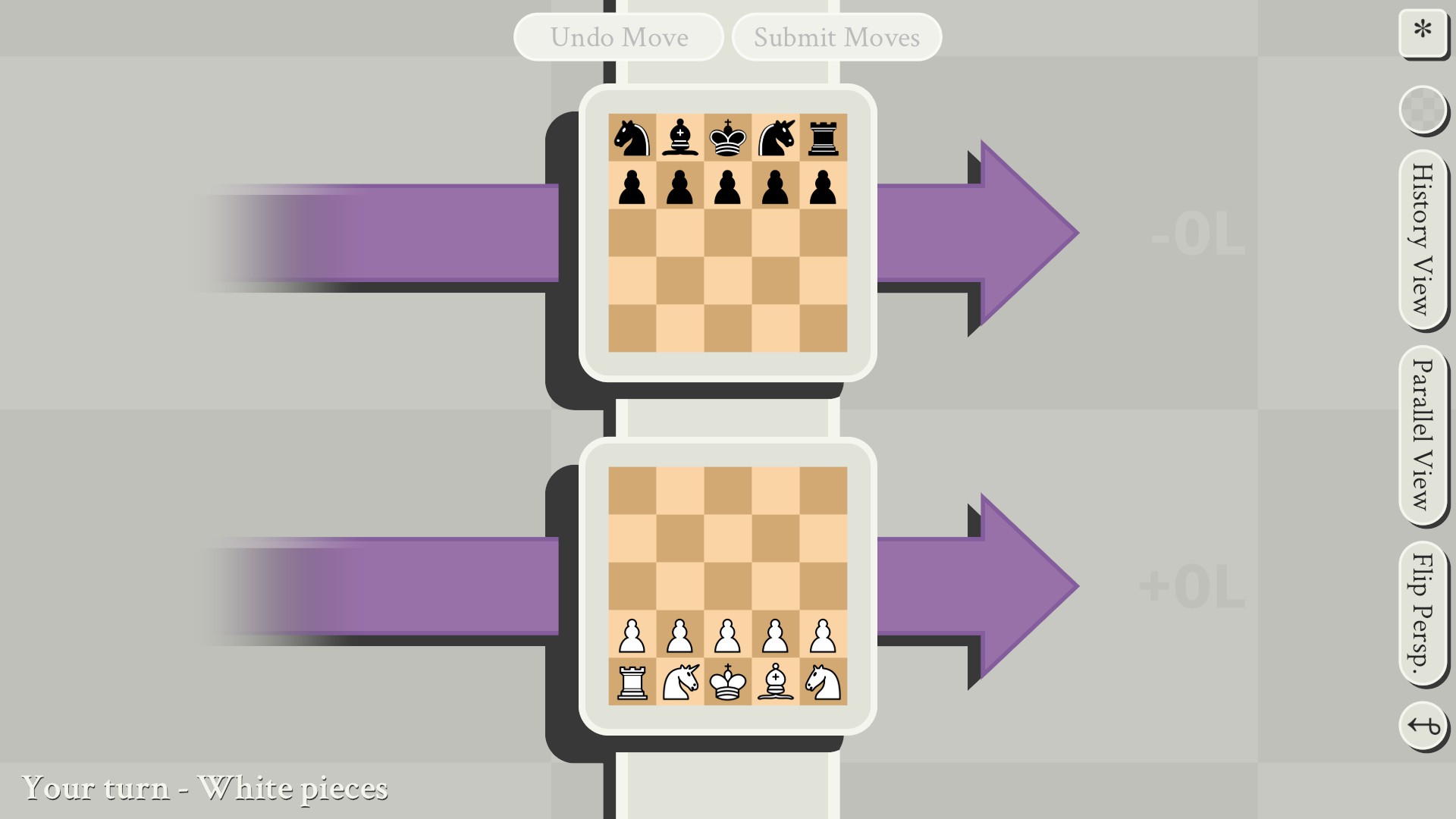

16. Two new pieces were added to the game, the “unicorn” and “dragon”. These are effectively just continuations of the idea that rooks move through one dimension at a time and bishops move equidistantly through two dimensions, so unicorns must move equidistantly through three dimensions at a time (meaning they have to move through time or parallel dimensions while moving diagonally on a board or both and either horizontal or vertical on a board), while dragons have to move equidistantly through all four dimensions (meaning diagonal on the board, across a parallel dimension, and through time). This ironically means dragons are probably the weakest piece in the game, since they aren’t capable of moving at all without other pieces having already advanced time then gone back in time to create an alternate dimension, and even then, they can only move on diagonals that will always create new parallel dimensions that will not be active ones unless the opponent is also recklessly creating more parallel dimensions. In every game variant I’ve played with them besides the “dragons only” (complete mindscrew) variant, neither I nor the opponent ever moved them because it’s an extreme hurdle to move them more than one or two tiles at a time, so they tend to just be obstacles your better pieces have to move around.

Alternate Game Modes

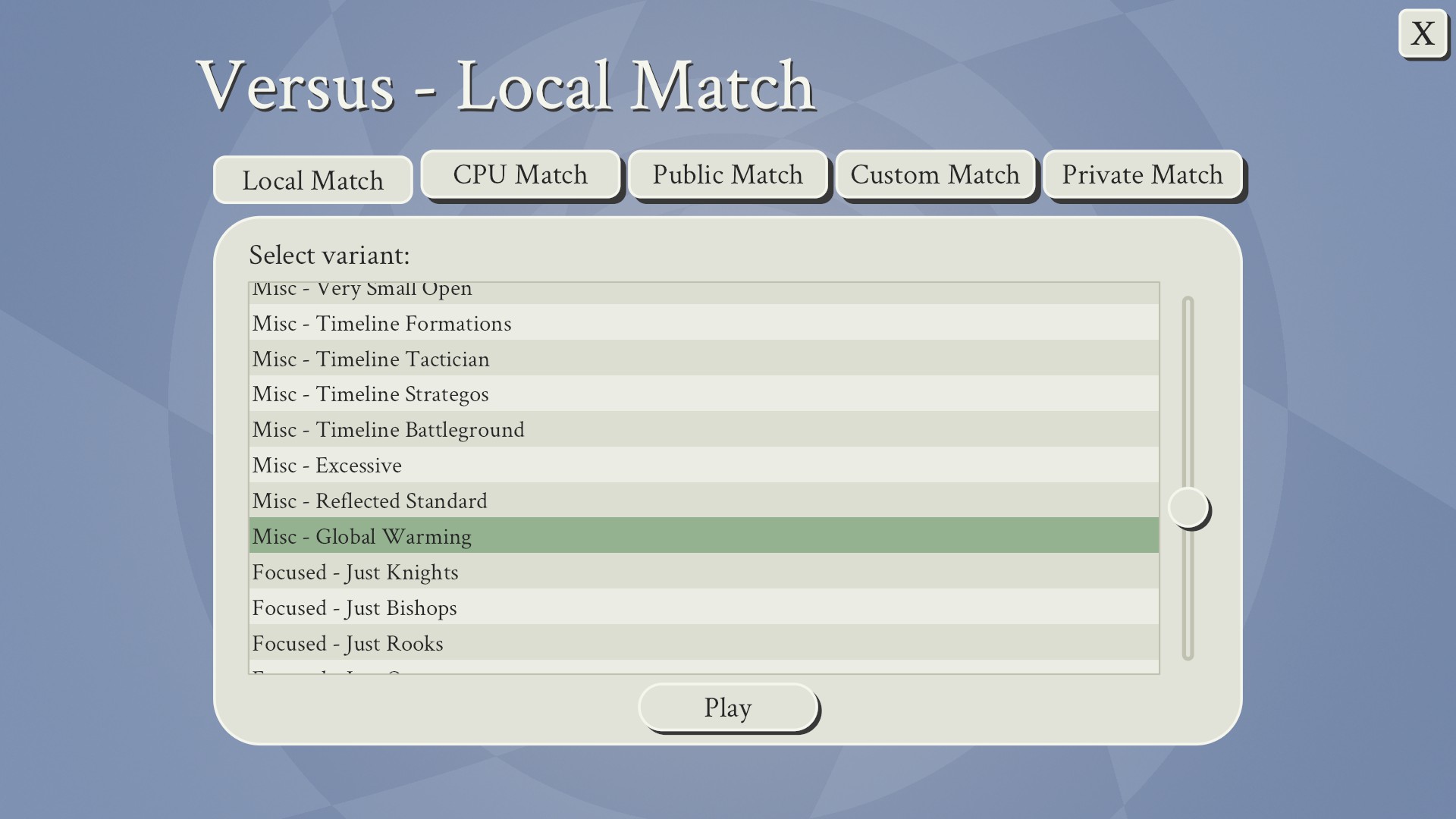

5D Chess has 33 variant game modes in addition to the “standard” game mode.

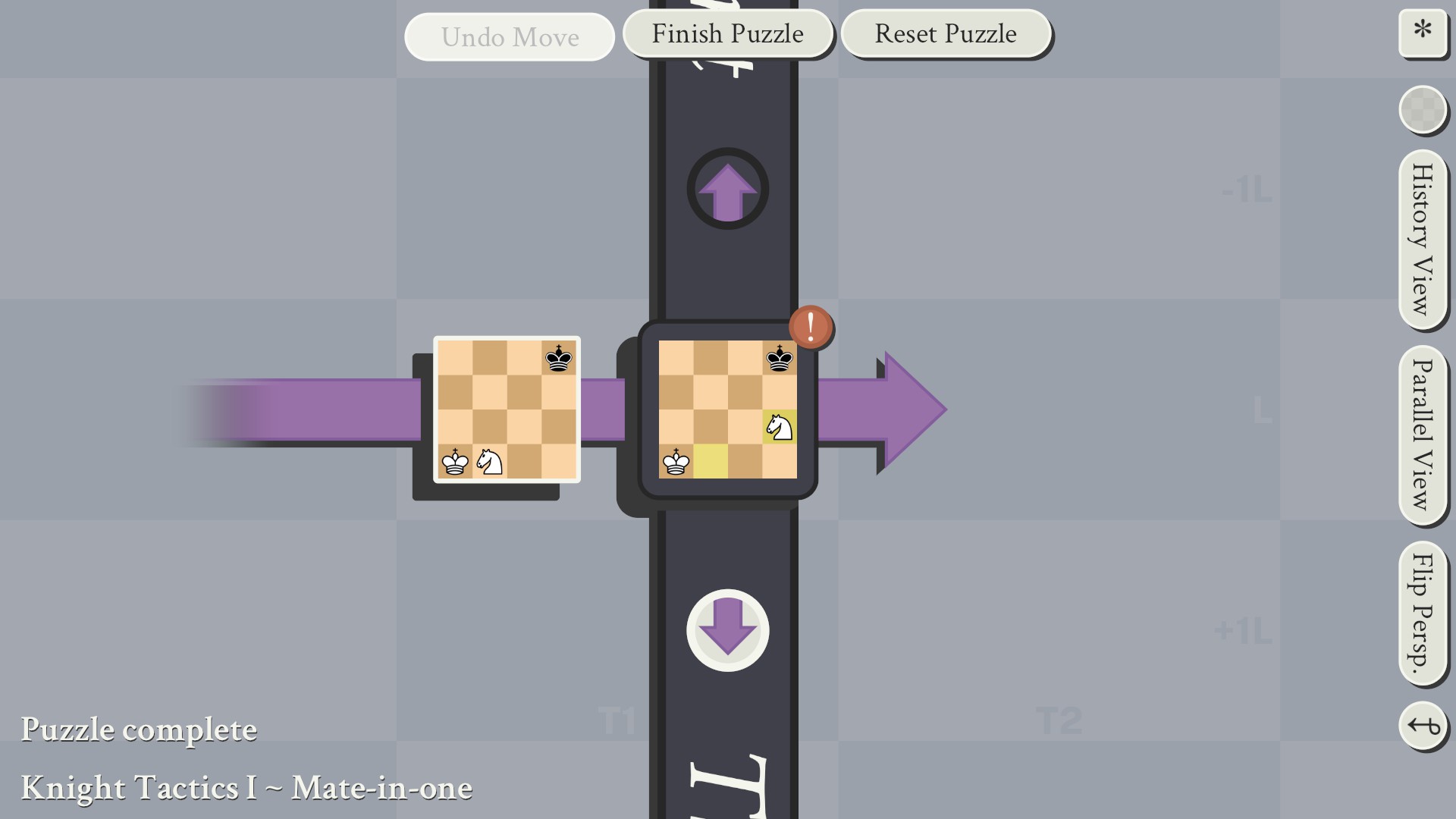

The problem is that few of them seem to have much thought put into them. Some are obviously not meant to be terribly complex, like the “checkmate practice” series that just has one white king and one black piece (or three in the case of pawns) where you can just test-drive time travel with different pieces.

There’s additionally joke modes like “Global Warming”, which has only one square and results in instant stalemate. Get it, because global warming will make coastlines disappear? Haha. It’s funny because humanity faces an existential crisis.

Anyway, it does create some question about whether all of the game modes are meant to be taken seriously. For example, the “Queens Only” game mode is basically reduced down to Tic-Tac-Toe levels, where whoever gets to be white basically has guaranteed victory if they don’t screw it up just because they can constantly put the king in check from turn 1, and then use a time-travel assassination checkmate because the black king has no cover. Playing black on that mode basically has you desperate to get the AI to stupidly accept a queen trade, and even then, you’re just down to the single-king-versus-single-king stalemate. The “Knights Only” is at the same level, where white automatically wins without black getting a chance to move its knights because you are in perpetual check. In fact, just like Tic-Tac-Toe, the “Knights Only” variant is so simple that it is easy to reduce to a perfect game. “Bishops Only” would be the same, however, even though a perfect game is readily apparent, the AI is incapable of recognizing it.

In fact, one variant, “Misc – Very Small” apparently had no testing put into it, because it’s a checkmate on the first round…

… so long as the “strong” AI isn’t playing!

Interface and Visual Information

Errant Signal once made a fantastic video talking about why violence is prevalent in video games, and the main thrust of Chris’s argument was that computers are simply bad at clearly representing concepts to players except through simulations of space. This is because things need to be expressible in mathematical terms for a computer to simulate it, but at the same time, making a game all about math equations happening off-screen is very difficult for players to actually grasp. Hence, space and physics simulation is mathematics where you can see the equations being played out since they represent the physical movement. (“If you throw a solid object this hard at this angle, where does it fall, and with how much force?” is a college-level calculus and physics problem, but it’s also a literal description of Angry Birds, a game popular among children who would recoil in horror of addition problems.)

One of the great advantages Chess has as a game is that all the information you need to know about it can be communicated purely through the position of its pieces. Anyone who understands the game can look at a game without needing to know or understand its history to be able to get an accurate picture of the state of the game and what strategies either side should be aiming for if they think about it for a while. (This is why I’m using even more screenshots than I normally would – it’s vastly easier to understand the information I’m conveying by seeing the rules play out visually through space than to just read it as text. This is also why having a simple text file be the only time in the game the rules are even mentioned is wholly inadequate for teaching a game this spacial.)

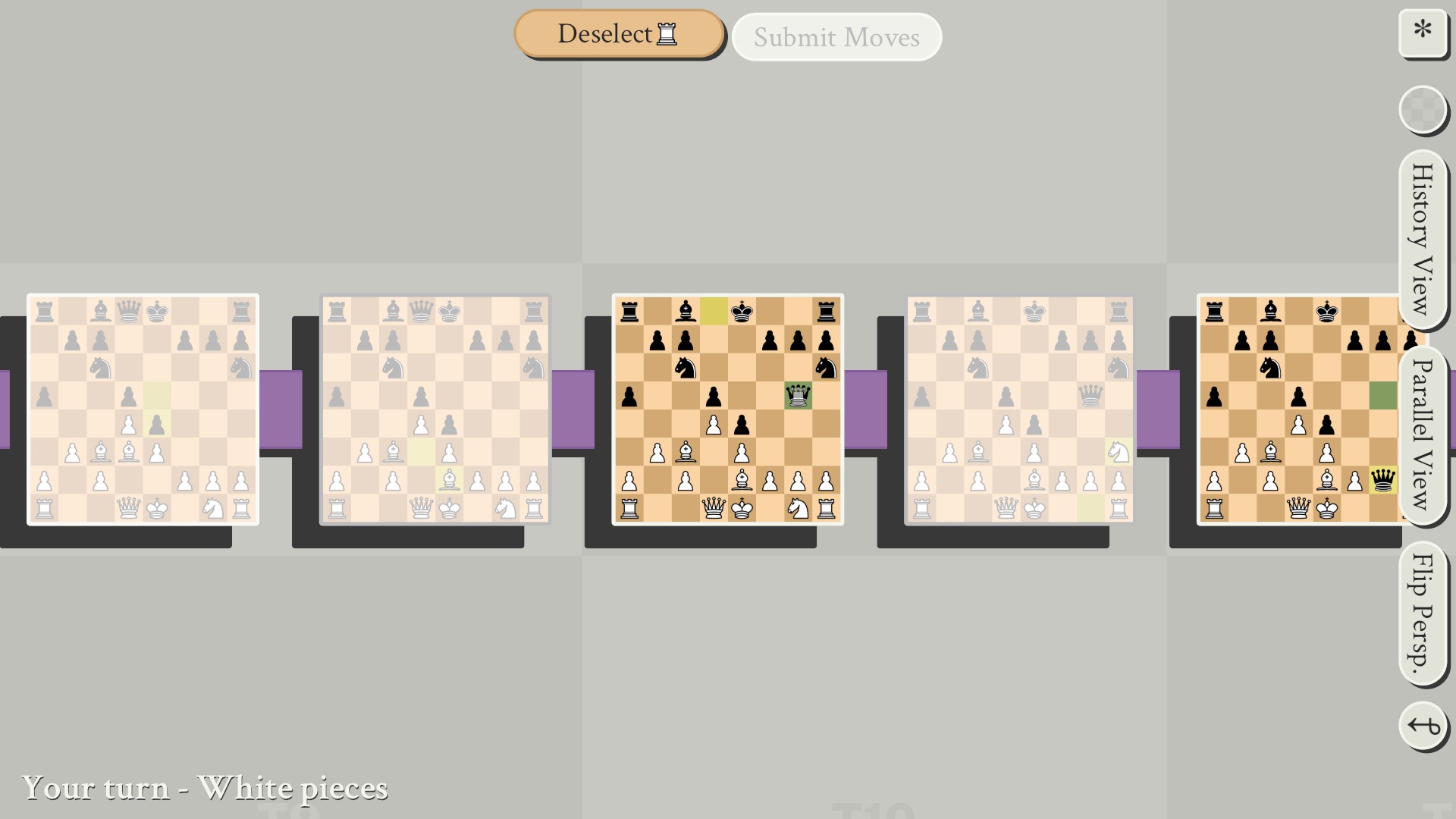

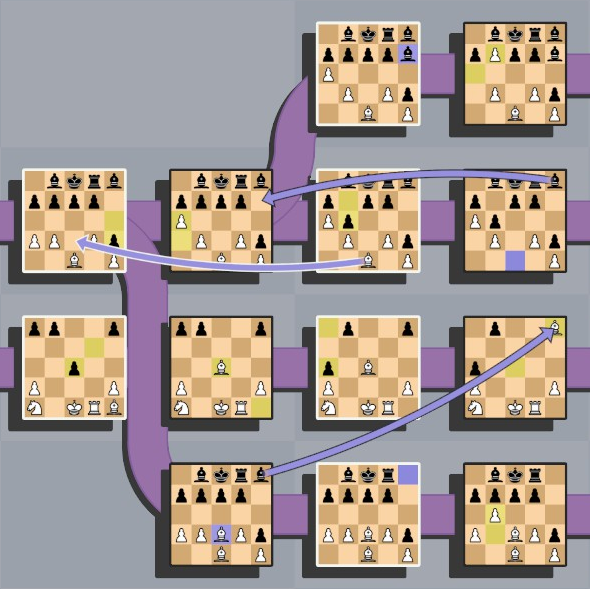

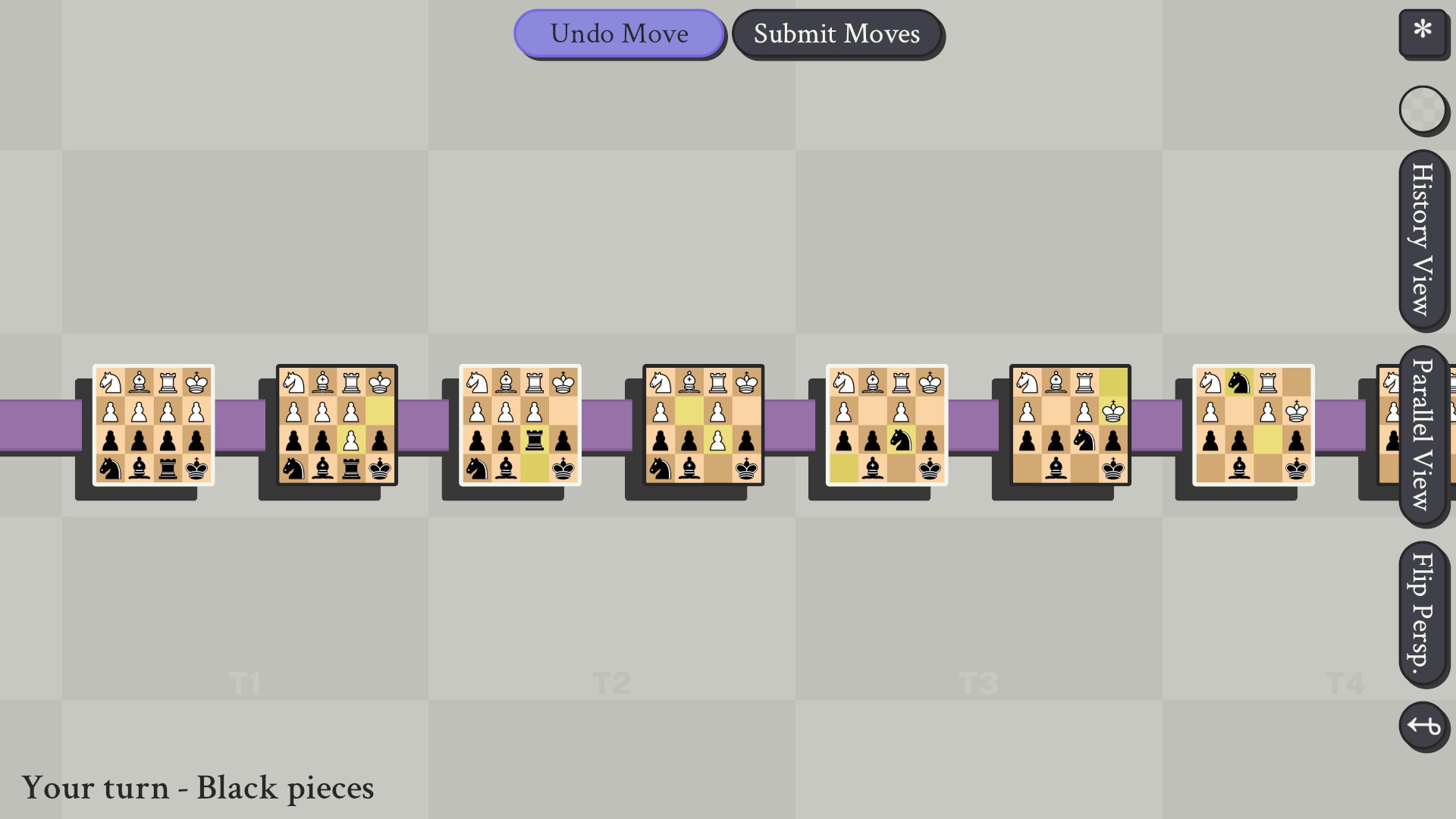

So what does this have to do with 5D Chess? Well, one of the biggest problems with 5D Chess is that its interface constantly contrives to avoid showing you all the useful information.

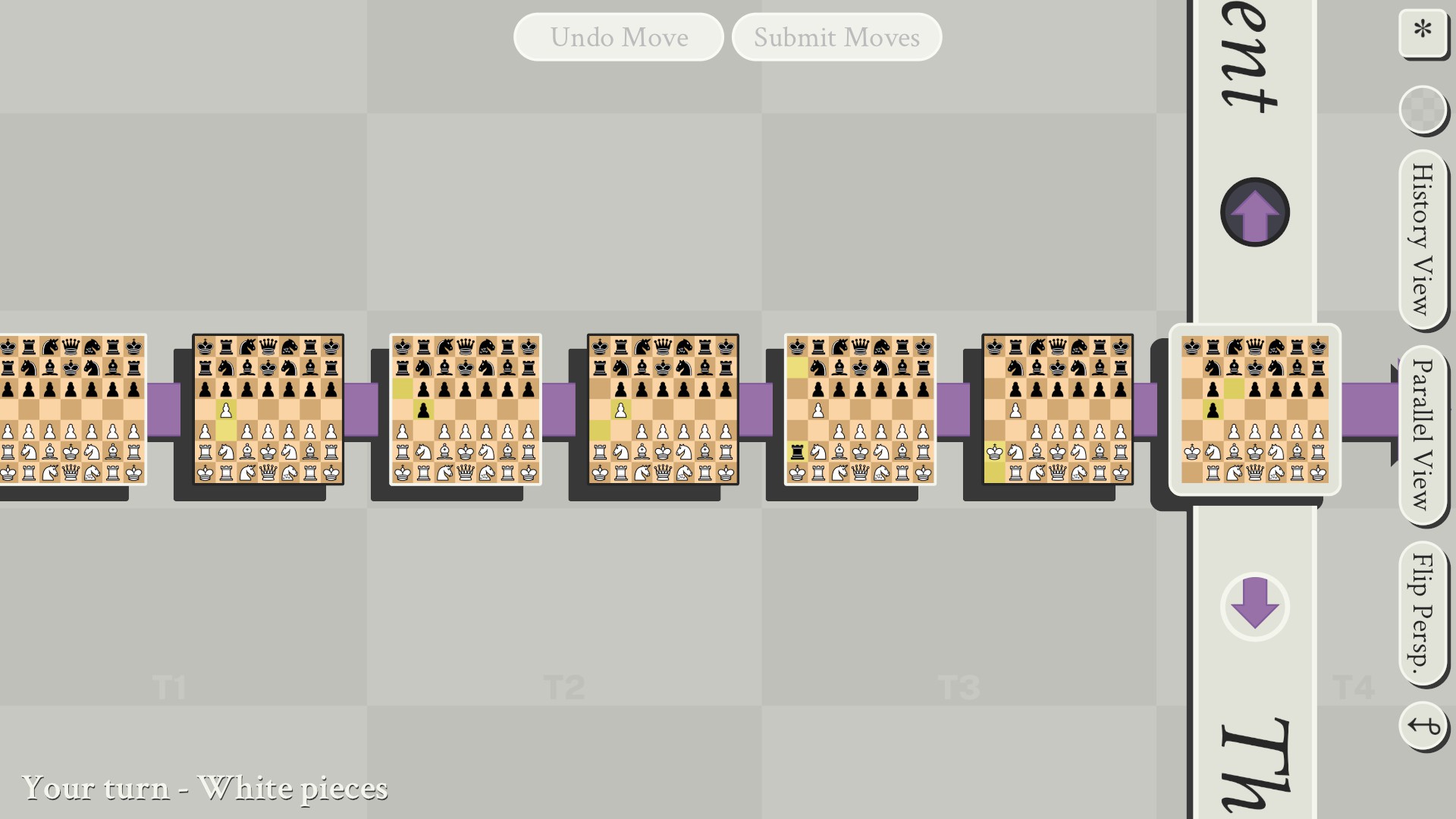

There are two alternate modes of looking at the game on the edge of the screen, history view and parallel view, but these are basically worthless for two major reasons: First, they take away the arrows you use to follow movement extra-dimensionally in the first place, meaning a mode meant to show information more easily obscures more information; Second, they don’t actually compress the view of the board meaningfully. In fact, because they’re making the 2D font pieces angled and harder to see, you typically have to zoom in closer and see less along the timeline than the normal view to actually make out the pieces clearly.

What the history view and parallel view are, I believe, trying to do is present a perspective that makes seeing moves through dimensions or back in time easier, but they simply fail at it completely, as you can’t draw a line clearly through the zoomed-out history view to see where the pieces can move by drawing some mental isometric line through the boards as you could do simply scrolling over while looking at a specific tile. (I.E. It’s not hard to find b3 on any given board.) Add in that most pieces are going to be moving more than one space back in time or through a parallel dimension and along some other axis of movement, and there’s absolutely no benefit to these view modes.

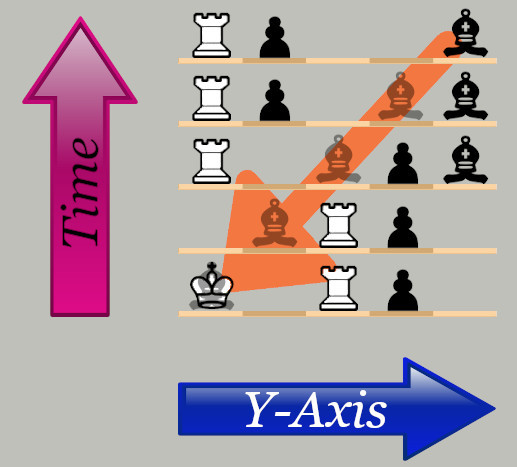

What this game actually needs is a view mode like the mockup I made above showing how a bishop moved between a gap in between the rook and pawn’s movement. Something that still presents the game in 2D (because the pieces are from a Unicode front), but which can show different axes in that 2D space, such as time as going vertical while a single slice of the board is presented horizontally, along with an ability to “scroll” through the different slices of the board. (By which I mean, Time is vertically stacked, the Y-axis is horizontal, and scrolling on the mouse sends you along the X-axis, displaying different slices of the Y-axis along time.) Again, the capacity to see all the states of the board(s) is a key aspect of presenting spacial simulation, so failing to actually shift the visible axes of the play area means players are denied key information they should have in making decisions.

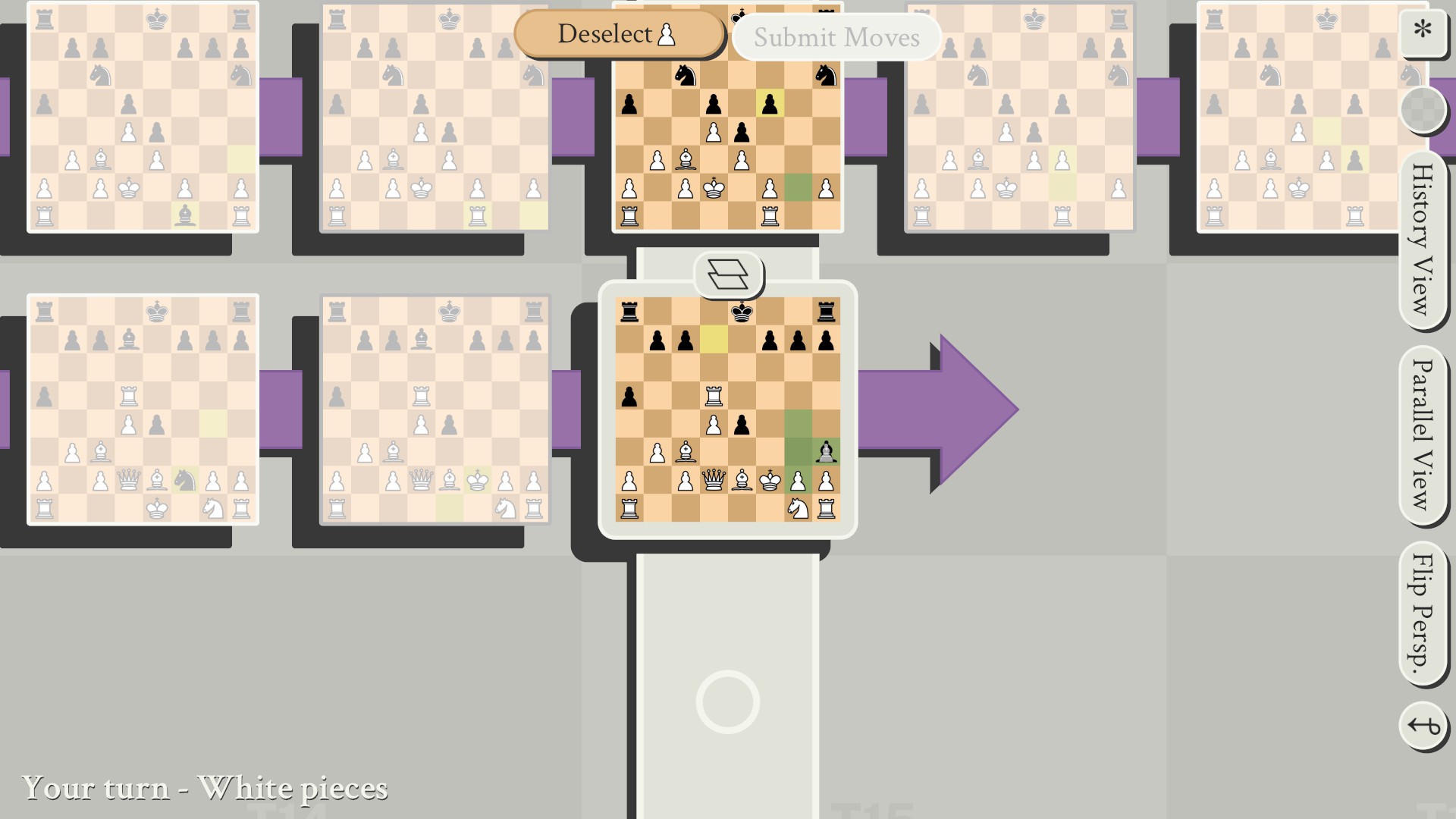

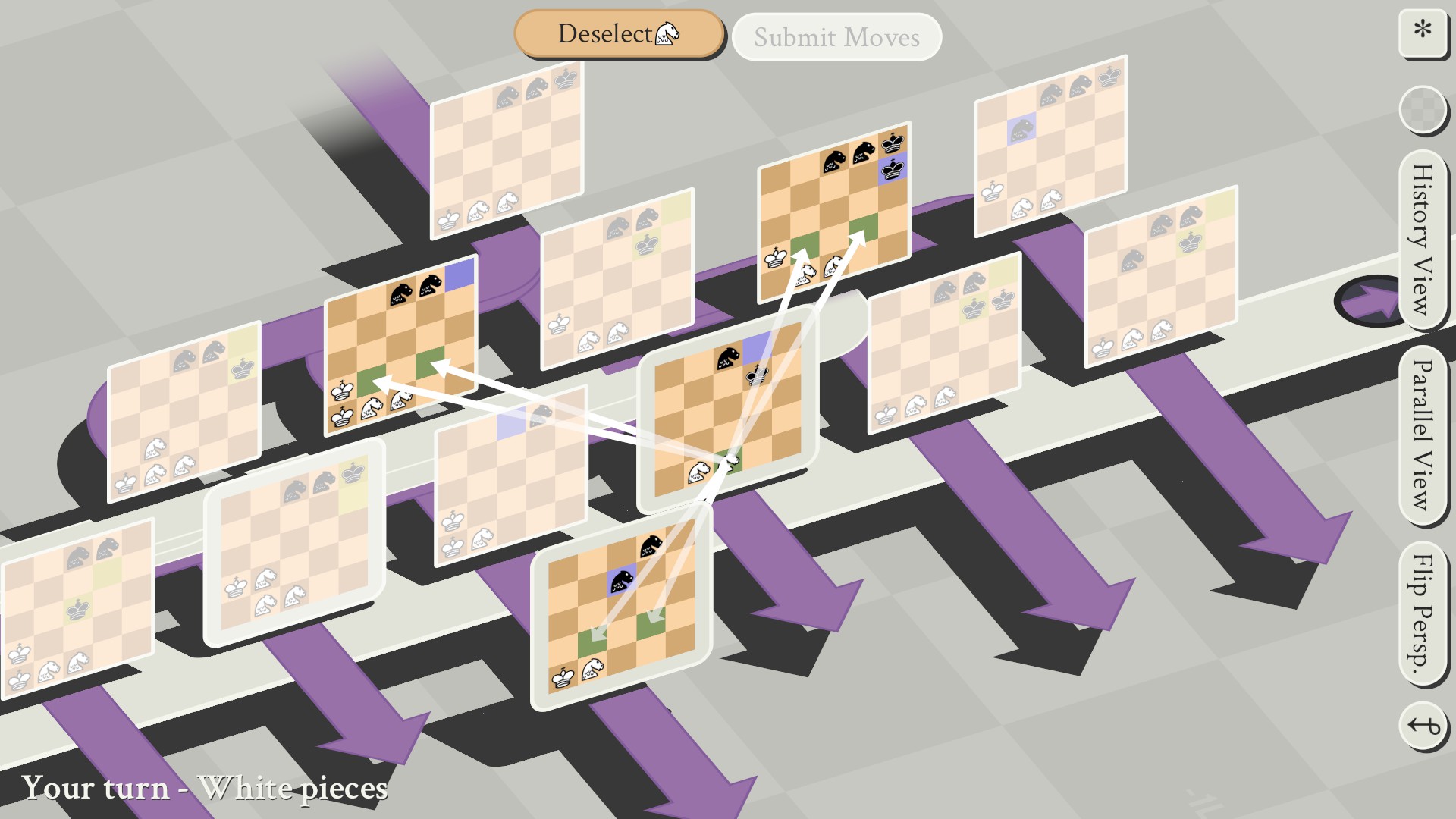

That said, there is also an unnamed viewing mode that you can access when you click one of your units to move them on your turn, and this one actually displays important, relevant information in a clear, concise way!

So, OK, you may be asking, if there is a good method of showing how you can move, what is the problem? Well, the key words here are that you can do this for your pieces. Remember, strategic thinking is about recognizing how your opponent will react to your moves, so naturally, this mode isn’t available to look at how your opponent can move in response! In fact, you can only look at what moves an opponent’s piece can make after you have moved your own piece and advanced to the opponent’s turn, but before you hit “submit”, and even then, only if you don’t scroll out, which means the interface makes it impossible to see more than one time state back into the past!

This is because the game ardently refuses to let you view it zoomed out enough to see more than a couple boards at a time, forcing constantly zooming in on active boards. If you zoom out to get a good look at where you want to send a piece back in time, clicking on your piece doesn’t count as clicking on the piece, it instead counts as “clicking on the board” if you’re zoomed out far enough to see anything, and instead, the click just zooms you in on the board in question, forcing you to constantly fight against the scrolling and zooming the game does against your will. In fact, when the computer gets a turn, they do this whiplash-inducing zoom-in, jumping board-to-board as each play is made too quickly for you to visually make sense of the boards zooming in front of the screen before the move is made and it flings you to the next board down.

On Multiplayer

Since the computer opponent huffs glue, if you’re going to want to play past the first dozen hours, you’re going to want to play with an actual sentient opponent.

Multiplayer relies almost entirely upon having a friend who also owns the game, hotseat games, using remote play for hotseat games, or going onto the game’s Discord server to ask around. There is a way to just fish for any random person who happens to be online with public games, but there is no real indication of who those people are, and because almost everyone uses private matches due to this, it’s nearly impossible to find anyone waiting for a rando to join a public game.

Additionally, there’s a major problem with multiplayer games, which is that you cannot save or suspend the state of the game in any way. This means if anyone needs to take a break for any reason, you need to forfeit. Unlike with the stupid AI, a game with a human player can take a few hours for players that are willing to create an insane number of branch timelines (or are just plain taking their time), so this becomes a real problem. There is additionally no play-by-email (PBEM) option, so it has to be a match played out immediately.

On Saving Games

Furthering the problem above, there is no way to save a game to look it over later except by screenshots or recording yourself playing. This directly harms your ability to learn from games you’ve played in the past if they go down the memory hole as soon as you hit “finish game”.

No Tutorial

So, here we have a game whose entire premise is capitalizing upon an expression specifically used as shorthand for “so complicated you’d need to be a genius to get it”, and that’s why this game’s manual is… essentially just a text file that’s two pages long and tells you to go to the Discord server to ask the other players to explain the game to you because the developer himself can’t be bothered. Several important game rules are not explained in the text file at all, for that matter, and basically just leave it up to players to blunder through with trial-and-error.

The game’s “puzzle mode” basically acts as a sort of placeholder for having a tutorial, as the puzzle solutions are often only one or two moves that are each explicitly based upon performing a specific function of a different piece. The problem is, to actively take part in the tutorial, you generally need to know what you’re doing, which means that you can either already know what you’re doing, and therefore not need the puzzles to learn anything, have an affordance – a setup presented so intuitively that players can understand what they are supposed to do just by looking at it – (and 5D Chess is absolutely not intuitive), or you can get stuck and have to just blindly mash every single permutation of moves until you happen to find one that works, and even then have no idea why one move works and another doesn’t. The problem of “why could the computer go back in time in Opening Traps III but not in other checkmates?” is one that I had no clue how to answer. Even when I went on the forums to ask, three days of having people dismiss my question later, I still had no answer. Thanks to this game being based upon a meme for supposed genius, this is the sort of game that attracts the sort of Dark Souls-style “Git Gud” responses to anyone asking for help, at that. Even in the puzzle section of the Discord, people come on saying “this worked, but why?” because without any explanation for what the player is supposed to be learning or demonstration of why it worked, the puzzles are incapable of actually serving as a tutorial for someone who has to blunder in with raw brute force tactics and no grasp of the rules.

Don’t get me wrong, having an interactive play field to see the consequences of experimental actions is much better than just text explaining a concept, but it’s still vastly better to just have text explain the point of a lesson before letting the player experiment freely so they can try to accomplish their goals on their own. As it stands, the player doesn’t know what the goal is. It also takes extremely little effort to make a simple text pop-up explaining the lesson a given tutorial is supposed to impart for the amount of benefit it brings a player.

The way that the developer tells you to learn is basically just to Google it, because he can’t be bothered to put in instructions in his own game. The problem is, this is absolutely just throwing new players to the four winds and leaving it up to chance how or what they might learn. The first few videos I found were of people confused that they were getting checkmates because they didn’t understand the rules, which really doesn’t help things, and at first gave me the impression the game was actually broken. That’s not good advertising for the game if I was shopping for the game because if the first thing I can see is someone playing the game like normal Chess and concluding that the game is broken because they had not seen the rules or had a way to judge the game from any other context, I’d decide to skip this game until it was patched.

The developer suggests looking at guides, but most of the guides are about how getting checkmates against the AI is easy because it’s dumb as bricks, which really doesn’t sell your game too well either, there, dev. When I found a guide that covered every solution to the puzzles along with explanations of why they worked, it did help when I was stuck, but it was an out-of-date guide, and it didn’t cover my still-lingering question of when someone could go back in time to avoid a checkmate. I did find a link to a guide that was up-to-date in one of the patch announcement on Steam, but that’s going to just be buried in the community news feed as time goes on. Plus, that guide wasn’t as good at explaining things as the out-of-date one, so I still didn’t understand why the solution worked, which means the “tutorial puzzle” failed in its role due to the developer abnegating the responsibilities of making a proper tutorial for their game.

Having a Discord channel is fine. Some of the people I met were quite helpful. But many of them were there because they didn’t understand, either. The Discord channel has more people in it at the time of my writing this review than most I join, but it still can take hours to get a response on the #learn-and-teach channel. It shouldn’t depend upon what time of day it is whether someone will be able to get an answer to the most basic rules of the game. This also poses a problem if the game becomes any more or less popular as time goes on. After all, if the game is more popular, that Discord will get flooded, and you’ll have trouble being noticed to get your questions answered as more and more new people ask basic questions like how bishops move. If the game becomes less popular over time as people move on, then there will be stretches where nobody is on to answer any questions at all, and it’s a crapshoot whether there will be anyone both knowledgeable and friendly will be on.

Regardless, the “#learn-and-teach” channel is filled with people constantly asking the same questions, such as how does a bishop move through time, or why is a bishop moving horizontally through time. This is a clear and obvious indication that the game is failing at some of the most basic tasks of presenting itself to new players, and it’s not excusable to lean upon your playerbase to constantly have to patiently instruct new players to make up for your not bothering to state the basic rules.

A good game will compile all the information that a player needs to learn for the player and update that information with every version of the game. It shouldn’t rely upon hoping that third parties are not only going to do that for you, but do it clearly and well. (A problem with third parties is that you can start to have divergence in terminology. For example, one of the guides I read was talking about how inactive timelines are activated in the order of which ones were created first… which in a game about time-travel requires clarification that they mean in player-time, not game turn time.)

Artificial Stupidity

Another very frustrating mark against this game is the absolutely pitiful state of the AI opponent. While there was a widely-publicized match where a human grandmaster beat a chess program, that was back in 1997, and modern computer chess programs are capable of beating any human opponent about 95% of the time.

In 5D Chess, however, the computer should have a massive intrinsic advantage over human players. Computers are not limited as humans are in seeing things on a 2D screen. It can see 4-dimensional space as easily as 2D space because they’re basically stored in data structures the same way. All of the problems I’ve highlighted with the deficient interface being unable to properly show how each piece can move to the player in a simple, concise way all build up towards a tremendous advantage for the computer, which should be able to see things the human players cannot conceive. Computers, effectively, are the best 5D chessmasters ever to be created in the future and come back to beat us in the present. Too bad they wouldn’t deign to touch this game, because its AI is ludicrously rudimentary and seemingly incapable of strategic planning of any sort.

The AI is amazingly stupid. The first few times I witnessed it, I literally stared slack-jawed at the stupidity of the AI as it would do things like exchange its queen for a pawn.

Effectively, in this strategy game, the AI seems to play completely without strategic planning whatsoever. It literally does not bother to plan an entire move ahead. In fact, when I talked about how the “Misc – Very Small” variant could be beaten in a single move, the AI fails to see this checkmate… apparently because it is distracted by the fact that it sees it can put you in check with its pawn.

What this seems to imply is that the AI opponent literally is not programmed to think far enough ahead to distinguish check from checkmate when making a move, and therefore will happily throw out its pieces in suicide moves just to get a chance to put the player in check, even if it means moving a piece into an empty tile where it can be easily taken by another piece.

That said, I have seen the AI script make somewhat decent moves when playing the “standard” Chess board variant. These, however, tend to happen relatively close to the opening, and generally only when the AI has its queen, which it develops almost immediately and uses aggressively. Part of why I recommend taking the AI’s queen as early as you can is that its scripting seems to completely fall apart as soon as it loses the queen, and it starts just randomly pushing pawns forward, moving rooks back and forth or generally just throwing pieces directly into your units to get captured. I have the suspicion that there was an actual heuristic script being written once that was abandoned at some point, meaning that it has guidance to make not-entirely-stupid moves in the early game when it isn’t given pieces it can immediately capture or attempt to put a king in check, but these evaporate as soon as you leave these controlled conditions, and leave a suicidally aggressive AI that cannot see an entire move into the future in its place.

This also leads to the one place where the AI can actually play a very strong game – in the “Kings Only” variant.

Because kings can only move one space at a time and you’re forced into a tiny 3×3 grid, the only way to get a checkmate is to send a king back in time to past-checkmate a king that is out of position but cannot take a king that advances towards it. Going back in time creates a new timeline that makes you extremely vulnerable, however. Therefore, the “Strong” AI will never do it, and will exploit the fact that the developer never bothered to program in the rule in normal Chess about making the same move three times in a row resulting in stalemate. The problem is, the AI will never go back in time, just waiting for you to go back in time and create a new timeline, which, unless you’re very careful about making sure you are going back to a time when the king was on a edge, not a corner, will result in instant checkmate as the AI immediately exploits your going back in time with a past-checkmate.

This king-based checkmate is easily one of the most difficult for a human to comprehend, which means it plays the most into the hands of an AI that can see 4-dimensionally with ease while the interface is not designed with allowing the player to see anything but the 2D board in front of them in mind and actively frustrates any attempts to see other perspectives.

Essentially, this is the time when the computer is capable of beating someone using actual strategic thinking: When there is literally no more than one move in the future, just taking advantage of any opportunity to exploit. The computer can only win in a mode that specifically stunts strategic thinking.

Graphics and Sound

You’ve seen all the graphics in this game just looking at the screenshots I’ve displayed already. Basically all the graphics are open source. The pieces are actually a True Type font called Cases, which is available for free, presumably made into a vector. I’m not disparaging a solo developer for using those, it makes perfect sense to use free assets that are perfectly usable.

The problem comes with the only pieces that are new, the unicorn and dragon. So, guess what? Those are clearly a knight redrawn to look very slightly different!

I at times was confused by the unicorns because I genuinely thought they were knights and didn’t understand why they couldn’t move. (In fact, I had to revise this article after finding a screenshot where I was labeling a unicorn a knight…) The unicorn literally is just the knight art mirrored and with two extra lines on its head (and the ears already make a smaller spike in the same general area, so it’s a matter of relative size). The dragon art feels downright lazy, and the silhouette is barely different from the knight, relying upon you seeing the scales drawn on the neck to really differentiate it. Remember how I keep saying that the key to situational awareness is keeping zoomed out so you can see multiple boards? Well, guess what pieces you are going to get confused for other pieces first if you zoom out – the ones with distinctive silhouettes, or the one that just has some curvy lines drawn on another piece?

This can be quite easy. They’re abstract images, the only thing it takes to make a good icon is literally just to make them visually distinct from one another. You could have made them something cool, like a badge and called them “time cops”. You could have made a thin, wide stylized circlet and called them “barons” if you wanted to fit the feudal theme. You could literally have just made a triangle and a square and called it a day, and it would have been better icons than these!

There is no music at all unless you count drumbeat sound effects that play in time to moves, and the “ambient sound” being a rumbling “whoosh” that plays constantly which I highly recommend you turn off so you can play your own music.

Chess isn’t a game that lends itself well to sound effects anyway, so I don’t find this to be a real negative. However, the drumroll and slow arc as pieces are moved back in time is far too slow considering as I may make the move a couple times to test the position’s ramifications and undo it, only confirming once I’m sure of all the ramifications of my move, and by then, the long arc with the drumroll is so time consuming I can literally make another move on another timeline in the time the drumroll slow-motion move through time is still going on. It’s like they think this is impressive when I’ve already moved on. (This is even without the nonsense “cinematic” version that takes longer and forces you to watch it all, while displaying nothing impressive with font icons.)

Interface Options

There are no rebindable keys. Once again, not everyone uses QWERTY keyboards, and accessibility options are never a waste of time. (As I write this, however, the developer is apparently working to make the game more colorblind-accessible, and that deserves kudos.) Nevertheless, every key should always be rebindable for PC games.

You also only get an indication for what keys do what in the “*” menu on the top right, and there is nothing anywhere that explains what the buttons on the interface do without you just mashing them to see what happens. The one that creates the “cinematic” back-in-time animation in particular throws new players for a loop, since that has no apparent effect when you press it. These are all things that should reasonably have a simple mention in the rules.

Relatively Easy Changes That Would Make This a Better Game

I’ll go ahead and give up on trying to suggest making a chess bot that doesn’t eat lead paint chips for breakfast, because that’s the sort of thing that’s both obvious and would take extreme levels of dedication to truly do well. It may honestly be easier to try to come up with a way to adapt existing open-source chess engines to work in 5D than create one from scratch.

Instead, here are some things that would be very easy to implement, and would greatly improve the game:

1. A save or suspend state. Seriously, I shouldn’t have to forfeit just to close the game for a minute.

2. Let players click on pieces while zoomed out. The interface shouldn’t fight against what the player wants to see or do! If I wanted to zoom in, I’d scroll in on it! A core tenant of interface design is that all information relevant to the decision-making process of the player should be available to the player in the same screen they are making their decisions. Again, a great advantage of regular Chess is that it allows you to see the whole play space at once. Players should be given the chance to see every relevant board on a single screen if at all possible. If you can’t fit every board on-screen, put arrows on the edge of the screen, or something to indicate where one can scroll, and add keys to allow quick-transit to those boards.

3. Allow players to have some sort of picture-in-picture mode for different boards. Let me drag a board to the corner to dock it, so that I can then pick up pieces and see how I could move several spaces back in time on that board, since the game currently doesn’t let me view that without dragging the board back and zooming in on the board which has the piece I want to move.

4. Allow players to select opponent’s pieces and see where they can move the same way that you can see where your own pieces can move. It makes no sense to take the time to program in a perfectly good way to see the moves a piece is capable of making to visually explain a player’s options to them, and only let players do that with half the pieces!

5. Allow players to shift perspectives on the boards. “Parallel View” is utterly useless, and obscures information rather than makes things easier to understand. Create a mode like the mockup I put together before:

Allow players to change which axes are presented on the screen at once, and then allow players to use the scroll wheel or some other key press to change “slices” of this 2D-presented space. For example, you could have two buttons that just have different axes (X, Y, T, and L), and swap them around so that you could be viewing just one particular tile through time and timelines. (This would mean you normally see X and Y on a board, but can change it to T and Y as in the mockup above. You might then press keys to traverse timelines or the X axis while still showing that TY display.) This would especially be useful in combination with the “picture-in-picture” mode in suggestion 3, as it would let you see both the board in standard XY-axis terms and also see the board in TY terms in a side image to help visualize time movement.

6. Have a way to save completed games and have a “playback” function. Aside from being able to have bragging rights for friends, being able to see games played back will allow players to learn from their mistakes and improve.

7. Create some sort of “cheat mode” or “training wheels mode” that allows newer players to rewind back moves or possibly take over from an AI mid-game or give control back to an AI. As the game stands, if plays are made that a player doesn’t understand, or if they are blindsided by something, the game just moves on, and players are basically forced to forget their mistakes rather than learn from them. Letting new players go back to the position they were in and take their move over again can help them see what their mistakes are more easily. It’s a feature I’ve seen in other Chess games, especially ones aimed at being all-ages, and it seriously helps if you want to teach someone younger. (Alternately, you could combine it with the above, and allow players who finish a game to restart a saved completed game from a specific point just before they made a bad move, and therefore can see how the game would turn out differently if they made a different decision.)

8. For Chess’s sake, make some variants with larger boards! The smaller boards (4×4 or less) are playing Tic-Tac-Toe, where the “perfect” solution is easily found and you can get guaranteed mate in 3 moves or less. I know the AI can’t handle actual strategy, but that’s no reason not to have larger boards like a 12×12 board. With something like a 12×12 board and starting with three different timelines, you might even have an actual reason to pull out unicorns! (This also opens up the possibility of something like a four-person Chess game, although that is more complex as a suggestion.)

Verdict

5D Chess is a fantastic concept, but lackluster implementation that makes a confusing topic harder on its players than it needs to be. You can certainly have fun playing this game with friends, but it could be vastly better to play if more effort were put into properly displaying information to the player and the variants are a joke with half of them being easy wins due to a lack of playtesting.

In spite of not being listed in Early Access, the game is at least being updated constantly as I write this. This means those who buy it are basically paying beta testers, as the game is being developed in response to the flaws players point out. The fundamentals are there, so if the interface were made to actually convey the information it needs to and not fight the player’s inputs, this would be a game I could wholeheartedly recommend.

Your review is extremely useful both as a tutorial and as a review. While I don’t agree with everything, I agree that the game has its limitations and that the interface could be better (for example, by making history view worth using).

I also think more options and more customisation is needed, and definitively a save feature.

This is the most well-balanced, constructive and explanatory review I have ever read.