A Place for the Unwilling: Meet me on the corner of Kafka and Lovecraft, one block north of Dickens.

Type: Single-player

Genre: Adventure, Mystery,

Exploration

Developer: AlPixel Games

Publisher: AlPixel Games

Release date: 25 July, 2019

A stranger from a city you’ve never heard of has recently committed suicide, and his will lists you as the beneficiary of his business, claiming that you were best friends as children back in a long forgotten orphanage. He wrote a letter explaining that although he took his own life, it was the city that made him do it. He mumbled dire warnings about dark forces at work, then concluded with a plea to watch over his widow and save her from the ominous machinations of the city itself. Who was this person, and why did he kill himself? Why did he fear the city so much? And who is behind the string of grisly murders that has gripped the city since your arrival? You may have inherited his business, but you also inherited questions as murky as the foggy streets that now beckon you deeper into this city, and an unknown fate.

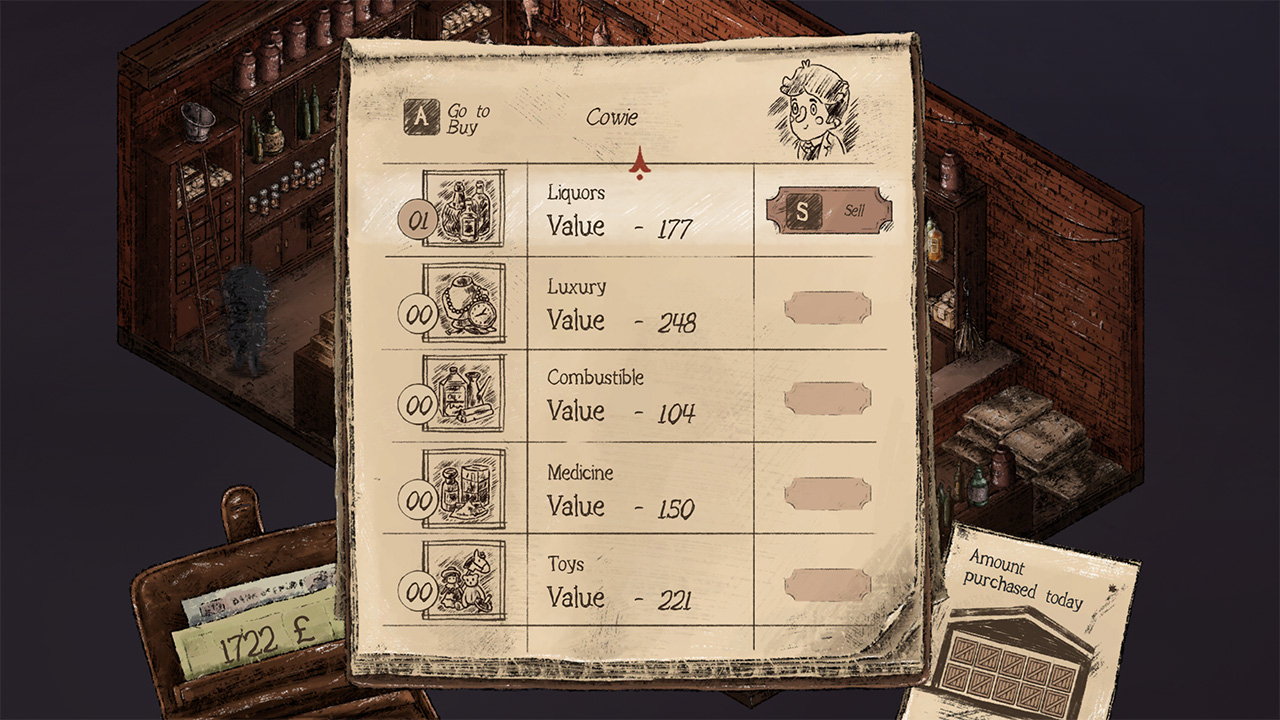

City Symphony

In A Place for the Unwilling, the new narrative based exploration game, you control the main character who must navigate through a maze of city streets, alleys, docks and markets in a race against the clock to solve the mystery of your friend’s death, and uncover the hidden truth underlying the increasingly shadowy city. After 21 days the story ends, and each new day represents a limited opportunity to explore and discover as much of the story as you can, a pocket watch in the corner haunting your every move. You can talk to characters, obtain tasks, engage in trade, research books and newspapers, bet on literal rat races, find hidden rooms, and try to ingratiate yourself to one side of the class struggle, or both if you dare. But you have to choose wisely how you spend your time and money, because you only get one chance before the story moves on, with or without you.

Them VS Them VS Me

Despite the surface appearance of an adventure game or isometric RPG, Unwilling is 100% about story and is more like a 2D walking simulator mixed with a visual novel, than anything else. It has enough interactivity to make you feel part of its world, but the story itself is quite linear, and the outcome is more-or-less fixed (with some minor exceptions).

In most narrative titles like this, you explore a large world to uncover bits of a story, and the game only advances when you make a new discovery. Unwilling is a bit different. It’s heavily time based; the events of the story unfold over the course of 21 game days, and everything progresses whether or not you’re ready for it, the clock is literally always ticking. In that regard, the main plot feels quite independent of you, the player. It’s like the gears of some great scheme have already been set into motion and you’re just there to observe the machinations.

Due to the rushed pacing and extremely fragmented storytelling, the narrative feels disjointed most of the time. It’s as if one grand story was written down and then run through a shredder, with the pieces being sprinkled across a game map for the players to reconstruct. What this means is that there isn’t a solid, cohesive or logical progression of discovery; no dramatic unfolding, or clever associative leaps to tie the story together; instead, it feels like you are piecing the plot together at random. Although this is fine from a conceptual standpoint, it does reduce the dramatic immersion considerably, and makes you feel more often than not like an accessory to the story, rather than an integral part of it.

On the other hand, there is a lot of story to be had in Unwilling. So much so that it’s impossible to get it all in a single playthrough. And in the game’s defense, that’s the whole point, I think. You have time in those 21 days to befriend only a few of the game’s many characters, and from each character you gain a different perspective on the main story. So in that regard, Unwilling is very prismatic, a seemingly simple story that changes depending on what angle you view it from. This gives the game a high level of replayability, if only because you’re almost obligated to have a second or third playthrough just to get the full picture.

For a game so completely dependent on it, how is the story in Unwilling? Although it is a hodgepodge of different elements and themes, the main narrative is, on the whole, successful, though it does keep you at an uncomfortable distance for most of its length. There are multiple competing themes, with some meshing better than others. Life in the city, your interactions with people, and even your goals are fairly Kafka-esque; there’s a sense of bureaucratic despair that looms over everything, and a certain impersonal terseness with which you engage in daily life. The absurdity of the city and the incongruent reactions of its citizens definitely contribute to this alien sensation. When characters address you, it’s like they’re each in their own private world, and are offended that you are somehow not in on it. As the plot progresses and more of the mystery is revealed, hints of Lovecraft can be seen, with horror and sci-fi elements mentioned, along with some ominous secret knowledge. The game’s setting and overall trappings have an unabashedly Dickensian flair, with tales of orphans, street paupers, class struggles, scheming shopkeeps, gossipy spinsters and the general rough and tumble life amidst a sooty industrial society. This combination of horror and mystery fit brilliantly with the pseudo-Victorian setting, despite the bizarre and impersonal qualities of the storytelling.

The game itself is very passive, and coupled with the fragmentary nature of the storytelling, makes it feel like what you do doesn’t really matter; and, in truth, it doesn’t, because the game is designed to be repeated many times so a lot of the story points are simply explained away with the stereotypical pillars of Fate and Predestination, meaning that your best intents as a player, and as a character in the story, are somewhat inconsequential; you are indeed just a cog in some larger machine. This makes the game a touch anti-climactic. Relying on fate is a cheat because it ignores the human element of choice, and means that there’s no reward for making the “right” choice, and no drastically different outcome for making the “wrong” choice.

Even a Stiffbutt Has to Take a Stand

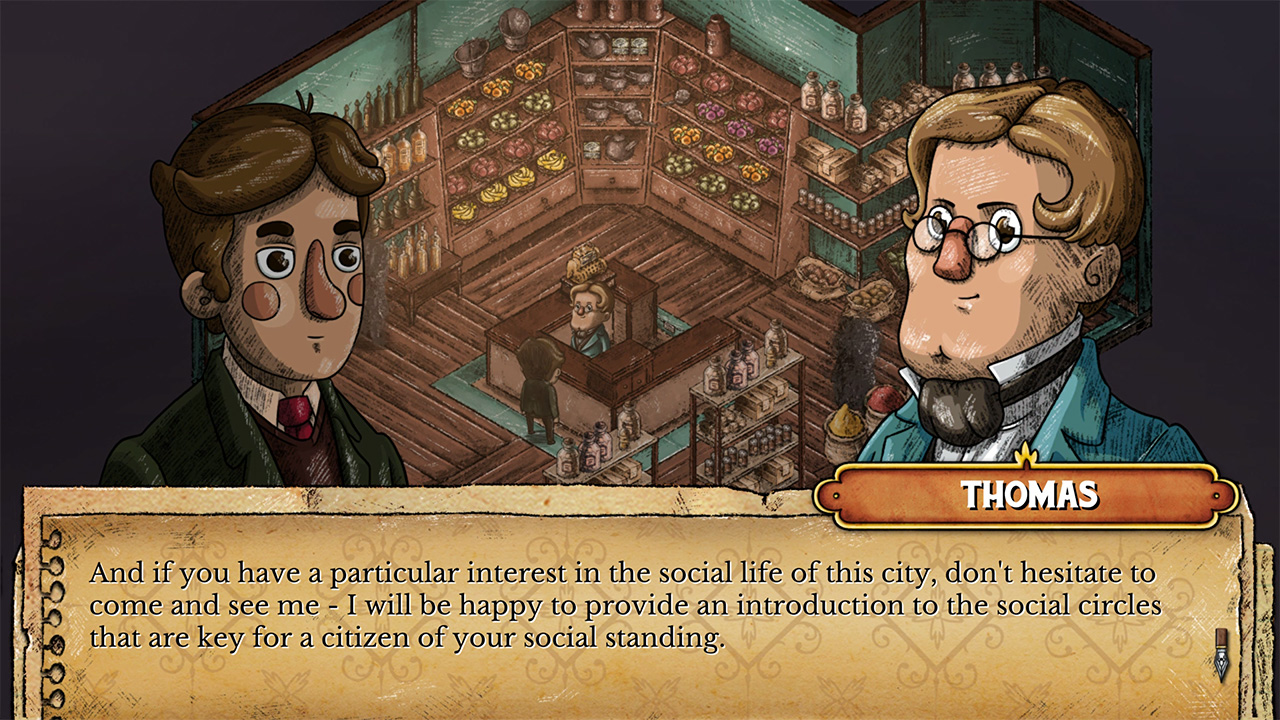

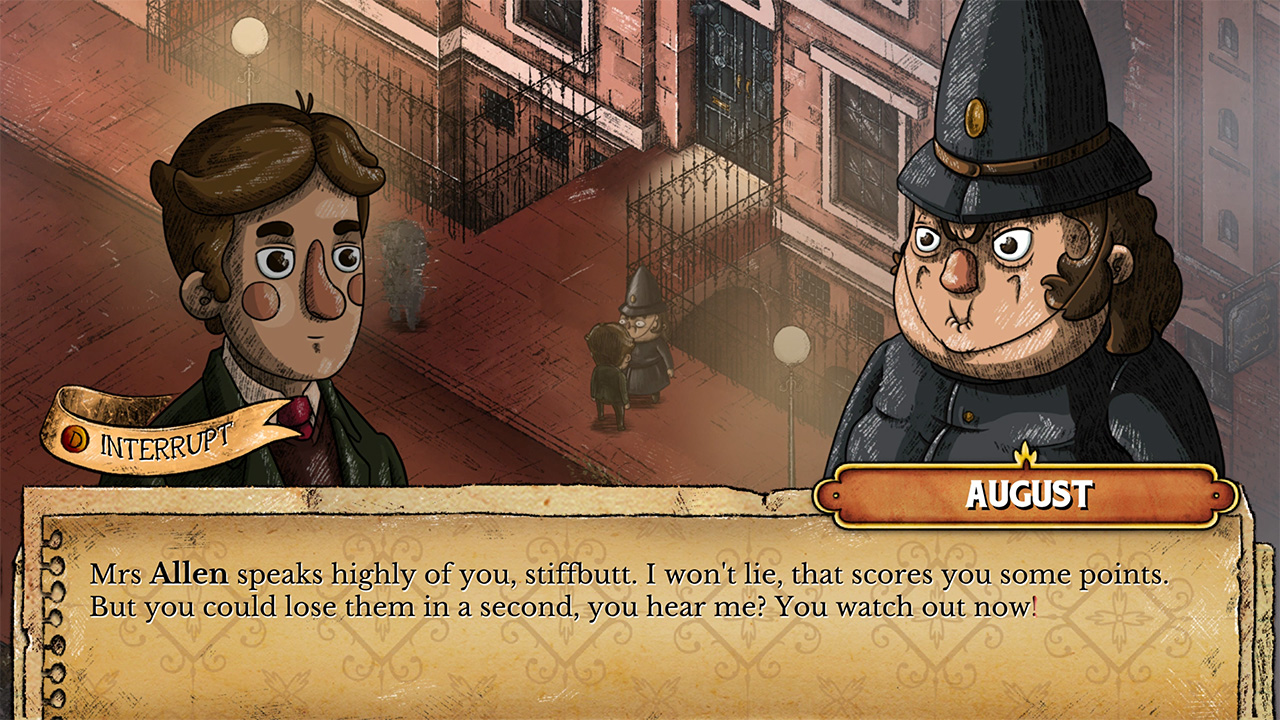

Except for some brief voice-over in the intro, the game is entirely text based, so it’s a bit unfortunate that the writing itself is awkward. To be quite fair, the writing is translated, so allowances should be made for that. Still, it’s the style that feels a bit over the top at times, like it’s trying too hard to capture a certain idiosyncratic characteristic, and instead comes across as cliched. This is most evident when conversing with other characters.

When chatting with the game’s many characters, it’s more like you’re being talked AT than WITH, and most conversations usually end in them calling you a “stiffbutt,” which is the game’s wonderfully brilliant catch-all insult. This limited verbal variety might be due in part to the “replayable” nature of the game; many of the character’s pre-determined responses do not take into account your actions, and so feel disconnected from what you are doing as a player, making their banter sound generic and distant. This is confirmed on multiple playthroughs, when characters will say the same thing to you even if the circumstances are different. In context of the grand story this is all fine, of course, but it is a reminder that Unwilling is very linear, and any appearance of player choice is illusory.

On the other hand, discovering the hidden insights into these characters provided some of the richest parts of playing this game for me. I love everyone’s backstories and side quests. For that matter, I had more genuine interest and investment in the side characters and their plights than I did the main story. While the main story is an uneven mish-mash of weird ideas, the personalities and stories of each of the characters that inhabit this unfortunate city possess the most life in the entire game. During your 21 days you’ll have the chance to get to know a few of them more closely, and as you engage in conversation, do little fetch quests, or help them out in other ways, they’ll confide more of their history to you. It’s in these small, intimate and personal moments that Unwilling really shines.

To those that live there, a city is not about its history, its monuments, or architecture, it’s about the people. That’s true of Unwilling, and makes it a city worth visiting multiple times, even if you are just a tourist.

Love Thy Neighborhood, Not Thy Neighbor

Although Unwilling isn’t trying to be a commentary about life in a city, playing through it I couldn’t help but wonder about some of the questions it raised. Do I consider myself a member of my neighborhood, even if, in all honesty, I don’t even know my own neighbors? How much of my identity should be defined by the place where I live? How much loyalty should I have to my city, and is it my city or am I its citizen? How far would I be willing to go for the “greater good” of my city? The answers, according to Unwilling, are grim.

Unwilling continually asks the player to take sides. Despite the city presenting a unified front, its people are anything but united. The city is divided by a river, with the rich on one side, the working class and poor on the other. These tensions continually boil over throughout the game, and even if you try to remain neutral, at some point you will have to choose a side. With the city pitted against itself, you’d think at least each neighborhood would be a concerted front; but there too is conflict. One merchant against another, one aristocratic family versus another, and even within that, each family member is actively plotting the downfall of the others. Such is the downward spiral of distrust that even when you do choose a side, thinking you’re doing the right thing and making the right choice, Unwilling shows you that a world ostensibly painted in black and white conflict is actually rife with gray. Ally with the rich and discover that they’re just a bunch of petty, elitist complainers. Help the poor and find out that they’re a bunch of ungrateful, ignorant bullies. Side with the City and realize just how much of an expendable pawn you really are. As a moral litmus test, Unwilling is inconclusive about its subjects, but it is content simply to say that there’s really no way to win in life, so just get as much out of the experience as you can with the short time you’re given.

Another aspect of the game that metaphorically matches our modern world perfectly is how strangers are rendered. Every person in this city is drawn as a swirling angry scribble. Scribbles walk up and down the main street, scribbles line the bar to guzzle their drinks, scribbles wait impatiently for the horse drawn carriage. If you do happen to get to know the scribbly owner of a boutique French shop, for example, then the sketchy cloud will disappear and you’ll see Florence, an actual person with a name, face and discernible identity. Such is real life too, I suppose. Surrounded by more and more people in our daily lives, they mostly remain unknowable scribbles. Perhaps this is unavoidable, for like in the game, there’s only so much time to get to know a limited number of people. Is that why there’s so much conflict in this game and in life, because we are either unable or unwilling see through the scribbles? If this is true, then the title becomes a question asking where exactly is a Place for the Unwilling? Perhaps that place is where we call home.

Pencil Perfect

I love digital art as a medium, in much the same way someone else might favor watercolors, or photography; they’re all different methods to express a creative vision. So I absolutely love that the visual style of Unwilling looks like an effortless merger between digital and hand-crafted artwork. The backgrounds and scenery are beautifully drawn with a sort of colored pencil feeling to them. The level of detail gracefully balances areas of high complexity alongside broad-stroked negative spaces, which blend perfectly with the use of light and color to simulate a world perpetually lost in lamplight and fog.

Perhaps my only gripe visually is that I wish the scenery changed in some way between night and day; as it stands, there is no way for you to differentiate between AM and PM; not even the watch face constantly ticking away hints at day or night. This can lead to rare occasions when you’re not paying attention and run out of time for a task, or a shop closes before you realize the day is over. To be fair, the lack of daylight is actually a running gag in the game, as many inhabitants complain about all the smog from the factories.

The character design is superb, and brings a hilarious and memorable face to each and every weird personality you encounter during your stay in the city. They’re drawn in a more classically cartoony style, almost Max Fleischer-esque, and it helps them stand out from the sketchy backgrounds while still matching stylistically. The design and shape of the characters themselves is endearing and satirical at the same time. In many ways they remind me of old Punch and Judy puppets; exaggerated in all the right ways so as to elicit sympathy and a laugh in equal measures.

The sound effects are great as well and deserve a mention. They really evoke the mood of each neighborhood you wander through, from the raucous din of the rambling back alleys, to the posh murmur of an upper-class social club. The music works well with the game, too. There is enough variety in it that each area has it’s own well-fitting theme, and it’s balanced so as to never over-power the game or its evocative ambient sounds.

A Few Sticking Points

Not everything about playing Unwilling was a smooth stroll through the park, however.

The control scheme is not my favorite, but considering how minimal the game is, I did get used to it. Although the game looks like it could be point-and-click, it is in fact controlled by physically moving the main character around the isometric map. Although you can use the arrow keys, movement is designed with controllers in mind first and foremost, so that’s the recommended way to play. I understand the reasoning behind this, which is to give you more immersion by making you walk everywhere manually, but for a game that demands multiple playthroughs, it would be faster and easier if alternate schemes were allowed, such as pathfinding with the mouse, or if you were at least given settings to remap keys or control input. Part of the gripe is that movement itself is a bit clumsy. For whatever reason, there’s the tiniest lag between when you push forward on the stick to when the character starts to move, or when you change direction. It’s only a mere fraction of a second, but this almost imperceptible delay makes it easy to misjudge movement and snag your character on a wall or other obstacle.

And that’s another sticking point, literally. The collision detection in Unwilling is quite aggressive. I spent far too much time getting stuck on objects, set pieces, and NPC’s. Tight doorways, narrow hallways, or debris on the road all represent potential roadblocks that will bring your character to a standstill. The same goes for the countless scribbly NPC’s walking around; get within a hair’s breadth of them and you’ll come crashing to a halt. Once, I was even trapped by this overzealous collision detection, as I got pinned between a potted plant and two NPC’s who decided to wander up and box me in at the same time. Unable to move, I had to spend money to fast travel away (the game offers a horse and carriage as a way to fast travel to landmarks, for a fee). Then again, perhaps getting stuck between strangers and a potted plant happened a lot in Victorian England.

The city in Unwilling may admit to having a rat problem, but the game itself has bug problems of its own. Crashes, glitched “quests”, garbled text, broken maps, and occasionally unresponsive controls, were some of the most frequent occurrences, to say nothing of the numerous typos and other random loose ends. However, to the developer’s huge and immense credit, the game has seen near daily patches since its release, and many of the issues that plagued my early playthrough have long since been addressed, and no doubt whatever remaining bugs I encounter will be fixed by the time you read this review. It’s also worth stating that even though these bugs were an annoyance, none of them were significant enough to be a showstopper, or prevent me from completing the game. The commitment to the game by developer AlPixel is evident, so there’s every reason to be optimistic about future support.

A Broken Clock Is Right Twice a Day

Time is a large component of Unwilling, and I’m reminded of my own fascination with time. As a kid I used to enjoy taking clocks apart, not because I had any great respect for time as some hallowed measurement, but merely because I desperately wanted to know how a clock worked. Once dismantled, I spread the pieces out across the kitchen table, examining and arranging them based on how I imagined they functioned. After I was satisfied in this chrono-cide, I simply walked away, leaving the guts strewn about, with no interest in attempting to re-assemble the clock. It was enough for me to know how it worked.

Such it is with Unwilling. To get the most out of it, you have to pore over each gear wheel, spring and lever that is scattered across the city map, and imagine in your mind how they fit together to form a larger whole without the benefit of having seen it in one piece. When assembled and viewed from the clearer vantage point of completion, however, the main story of Unwilling is the least interesting aspect of the game. As it turns out, the process of discovery is actually more satisfying than putting everything back together.

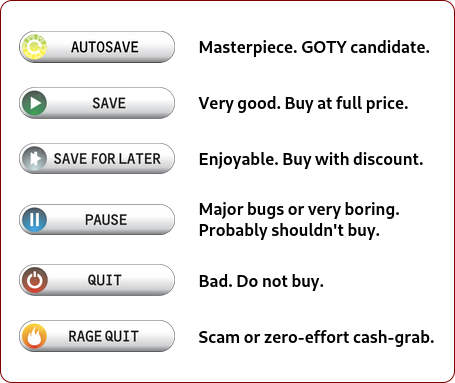

Verdict

Much like life, the plot of A Place for the Unwilling continues whether you make the right decision or not. In fact, the only way to fail is to make no decision at all. Time still moves on, the story still ends, but you just miss out on the rich details that made life worth living in the first place. So, forgo the race to the finish line, and instead savor each minor moment, each throw-away line of dialogue, each character quirk, follow each stray leaf as it blows down each cobblestone street visible under the flickering gaslight, lose yourself in the hum of a placid afternoon among the crickets and grass of a manicured public garden, become, willingly, a member of this city and its many varied people. For somewhere there is a place for each of us too; a place in family, or in community, among friends or colleagues, in our home or the cities and nations in which we live. For it’s in the process of seeking this place that we may, however briefly, see the real world as possibly a little bit less scribbly.