You’re not going to believe me when I say this game is a classic without playing it for yourself, but let me explain why you should give it a chance.

Type: Single-player

Genre: Action, RPG

Developer: WRF Studios

Publisher: WRF Studios

Release Date: Sep 21, 2015

Of the strangest titles on Steam, Bloodlust Shadowhunter may be the jankiest, the most unpolished and the most confused idea of a game while also being the most addicting ARPG I’ve ever played. In spite of its many visual, technical and gameplay issues, this game manages to create what is undoubtedly a new cult-classic about vampires like Vampire the Masquerade, although if you are expecting the same quality of storytelling or pen-and-paper features then let me to douse that misconception. Bloodlust is neither like the Masquerade nor is it anything like Diablo whereas Torchlight 1 is more apt given its dungeon design and single-player focus—Bloodlust is some monstrous conglomeration mixed with some procedural generated dungeons to create some unholy trinity of a game, and it’s absolutely wonderful.

At the risk of tarnishing any credibility towards my taste in games, Bloodlust scratches an itch that I never knew I wanted from this genre, namely incorporating more role-playing elements that work in tandem with these kleptomaniac adventures. Even describing what experience this game creates may be difficult to believe without playing it for yourself, which there is a free demo if you are not convinced but you must go into this game with an open mind. Like the first time you try wine, Bloodlust may be revolting from its initial impressions, yet over time the refinement of its ideas comes further into play until you’re begging for another glass.

Double, Double, Toil and Trouble; ‘Pyres Yearn ,and Torchlight Struggle

In order to understand what elements Bloodlust borrows, it’s best to understand the concoction one element at a time and see how the game differentiates itself when mixed together. These elements include the following: the vampire elements as an RPG; the Diablo/Torchlight design of its gameplay; and the procedurally generated dungeons with the overworld as a modern version of Masquerade.

From the start, you’re given a character sheet structured like a hybrid of Torchlight and Masquerade where you can choose Warrior, Criminal and Witch archetypes with clan reputations as well as racial options with stat changes such as Vampire, Half-Breed, and an unlockable race after finishing the campaign. Unlike those other games, these decisions are more tailored at the start than being permanent as clan reputation rewards and the skill system allows players to create their own builds. (Be careful not to invest all your stats into one, especially Persuasion, as many weapons and gear require two stats.) Some abilities like Bite, Vampire Gaze (a spirit projectile to scout and interact with objects) and Secret Vision are universal; in addition, every vampire can have a sire for every five levels invested into Bite. Sires are essentially Pets who cannot pawn off items, but they can scavenge and assist the player in combat. These sires also share attribute points gained when you level up, so whether you invest in one or four sires there are no extra rewards save for numbers. As you might expect with only one social stat for dialogue, these systems are simplistic yet also robust that the game never feels too easy nor too strict with your decisions. Combat and kleptomania are the focus, but not exclusively to make your choices meaningless.

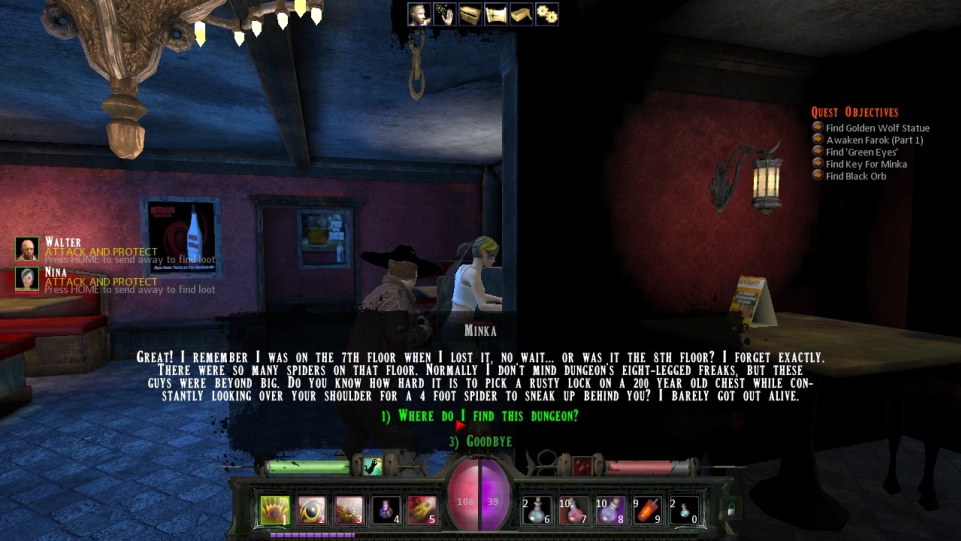

This aspect leads into what Bloodlust does and does not incorporate as elements expected from any ARPG like Torchlight. Quest designs, side-quests or main ones, are fetch-and-kill quests with very little, if any, narrative purpose save for some dialogue or cinematic rewards. This aspect is perhaps the most unfortunate because there are moments where persuasion or alternative skills can sequence-break the intended course for the player. Puzzles and alternative mechanics like lockpicking, disarming traps or safes, keep the gameplay from being completely mindless, although the Simon Says mini-game for remote traps is tedious. Level-design, however, is vastly different from what you might expect; one half of the game is a sprawling cityscape and sewer system with secrets galore to earn 200 attribute points as well as introduce you to areas that the main-quest never steers you towards, and the other are the six completely randomized dungeons each with 200 floors. That number may sound unbelievable, but the achievement doesn’t lie—and it’s as absurd as it sounds, especially with the fact that once you leave or enter a treasure-room, you go back to the top. If you exit, the dungeon will be completely random once again. In the game’s defense, however, most quests only ask you to plunder five to twenty floors, so the randomized nature keeps each trek from feeling the same.

The randomized nature is to the game’s benefit and to its utter detriment. As previously mentioned, floors never stay the same once you leave, and it can make one question why bother to reach the hundredth floor when you can repeat the first fifty twice. One reason is that the rewards get better the farther down you go and you gain extra XP the farther you go; another good reason is that certain floors are specifically made for bosses or a vendor-shop, which sells another component that may be given to you randomly in order to progress the narrative on the thirtieth floor. Certain items and quest-objectives require parts obtained from specific locations or a suggested floor, or they may be from random encounters like the Ogre’s eye. There are also other beneficial aspects randomly given to you like items for reputation bonuses, extra talent unlocks, repairing and alchemy stations, free maps, free coupons, etc. that make each journey slightly more worth its time. In my experience, this aspect never grated me nor hindered my progression with the main campaign, although if you attempt to go all the way down for every single dungeon you’re bound to return for every side-quest as everyone loves to lose something down under the city.

To Strike True When All that is Fair, Foul and Foul, Fair

Although these dungeons and the overworld have been discussed at great length, it’s important to note that had Bloodlust better distributed its randomness with the tailored content it could have solved the problem of wearing out its welcome. Instead of every dungeon having 200 floors (1200 dungeons total), it would have been better to scale them in difficulty along with 25 floor increments with new obstacles, puzzles, etc. from 50 floors at the start to the finale with 200. Each area would feel more distinct and not as homogenous as one another given its limited assets, although it should be noted that there is an impressive variety of enemies with distinct challenges to make up for the mundane areas. This result would still come out to around 875 floors, yet if they were better structured with an algorithm, then the lack of handmade environments like the Courtyard wouldn’t make the game dip so much in quality. Sadly, the same solution cannot be suggested to improve the narrative given its choice for quest designs.

Now it’s easy to see why the narrative is harder to make given its choice for quests. These quests perhaps sound weirder out of context, but they are like returning to town in Torchlight where someone asks you to find/kill something, then you go back into the suggested area to accomplish it. The difference is that everyone seems to lose whatever plot McGuffin they need for the day in the twentieth floor of a dungeon rather than on the kitchen counter. Finding these areas are often the first obstacle as hints are elusive and some details behind the quest may mislead you thinking they are within the city; the reality is every quest, except for maybe one or two after the prologue, is accomplished within these randomized dungeons. As a result, there is a noticeable lack of lore like the Masquerade which shared the world with the player as these quests all bog down into “Find random loot on random floor.” Clans, rules of vampire society and the overall mythos are on the wayside of the journey. When the game does want to include its narrative, especially the conspiracy and its moral decision, it feels surprisingly effective given how the rest of the game fails to build up to that climax.

Without spoiling what is admittedly a hokey narrative that feels out of place, the moral decision at the end is the one moment where the narrative made me pause. It utilizes all the personal investment you have made, your clan reputations and all the power you have accumulated, to be given a choice with a major consequence if you wish the good outcome. In any other genre this dilemma wouldn’t be noteworthy, but in a game where you are conditioned to loot, to get stronger, and to optimize your characters, this decision is the kind of cleverness that can twist the proverbial dagger in the chest of diehards. Although the writing nor the quests lead up to the finale, the mechanics themselves put you into a dilemma where you may sacrifice everything you have worked towards in the pursuit of victory or you may cave in to the pressure of power, which still would make sense given the situation. That moment was when I appreciated all the thought that had gone into this game, and it’s fitting for something that makes a bad first impression to make a great ending befitting its ambitions.

If Nothing Else, Remember This Game for One Thing Above All

Unfortunately, these many shortcomings are likely the result from the fact that this game was primarily designed, coded and written by one madman developer. (Did I forget to mention that at the start?) One-man projects deserve their own moment of praise, but I saved that information for the end to illustrate how much passion and thought was put into this project. The end result of all that devotion is this game the way it is, however flawed or unpolished it may be, and it is how this game should be remembered. Whether that excuses the visual or technical drawbacks is up to you, although I hope there is enough here to sate your curiosity to see that passion for yourself. If the game is not worth it at full value after experiencing the demo yourself, then perhaps consider it at a discount worthy of this man’s efforts. If not, there is always the sequel that comes out later this year.

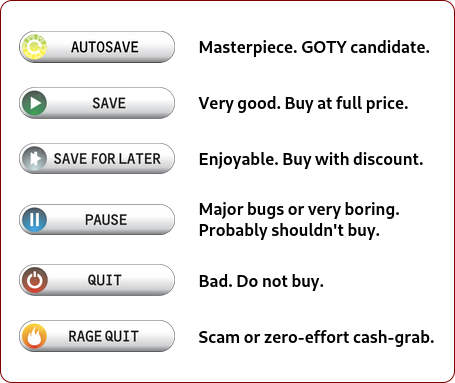

Verdict

Save for Later – If this game had the polish it needed, this game would be an easy Save rating; however, as much as I would say it’s great despite its issues not everyone will probably share that same confidence without playing it for themselves. This makes this game an easy game to pick up when on a sale that you think the developer deserves. Again, there is a free demo available to play the tutorial area and the Courtyard, so if nothing else has made up your mind you can experience the game for yourself and be your own judge. (Keep in mind it takes around Floor 20 or so for the dungeons to ramp up the challenge to a comfortable level, so don’t assume they’re all the same.)